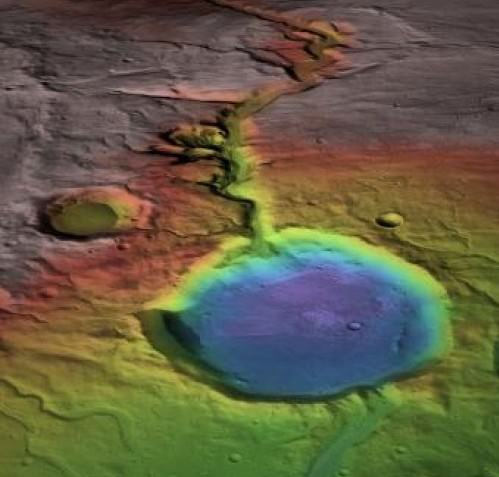

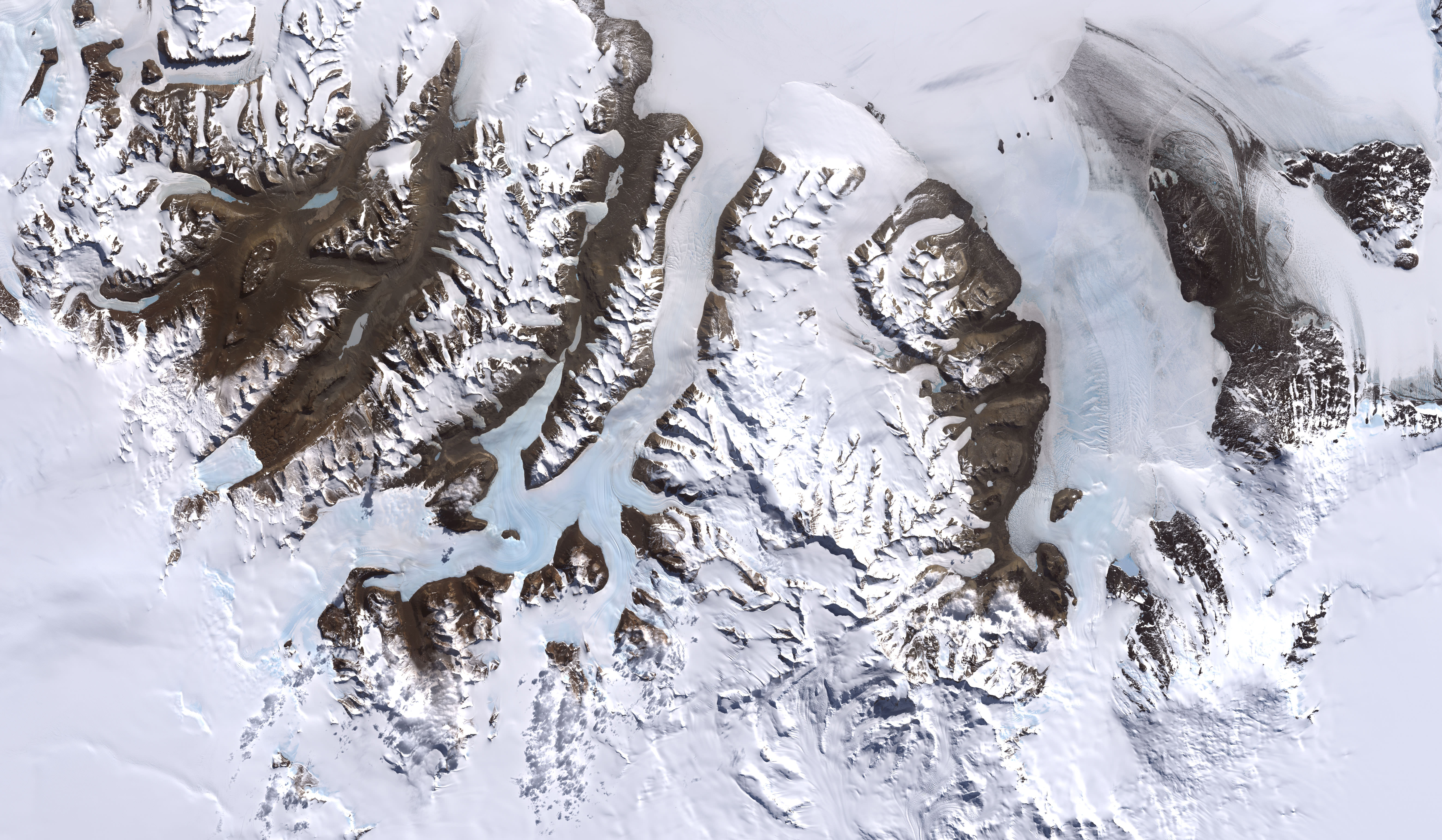

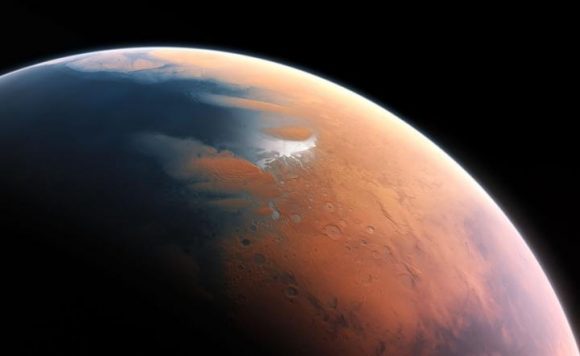

For years now, scientists have understood that Mars was once a warmer, wetter place. Between terrain features that indicate the presence of rivers and lakes to mineral deposits that appeared to have dissolved in water, there is no shortage of evidence attesting to this “watery” past. However, just how warm and wet the climate was billions of years ago (and since) has been a subject of much debate.

According to a new study from an international team of scientists from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV), it seems that Mars may have been a lot wetter than previous estimates gave it credit for. With the help of Berkeley Laboratory, they conducted simulations on a mineral that has been found in Martian meteorites. From this, they determined that Mars may have had a lot more water on its surface than previously thought.

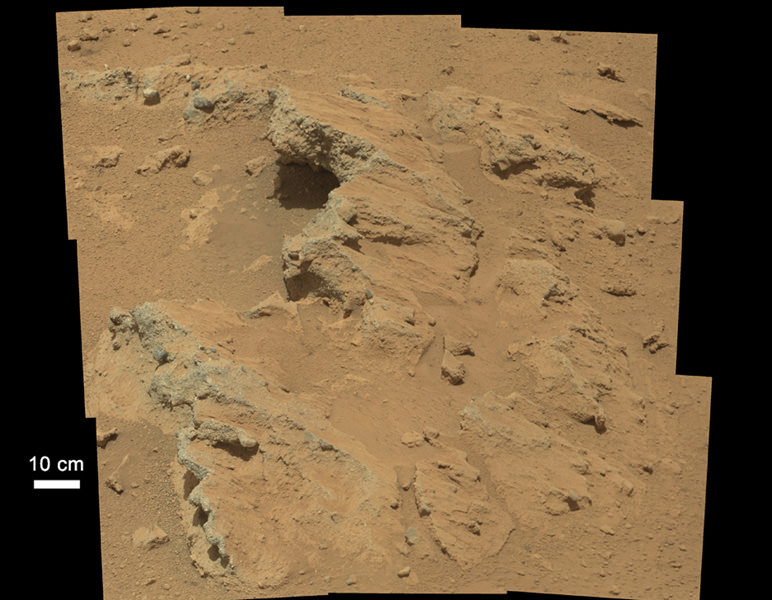

When it comes to studying the Solar System, meteorites are sometimes the only physical evidence available to researchers. This includes Mars, where meteorites recovered from Earth’s surface have helped to shed light on the planet’s geological past and what kinds of processes have shaped its crust. For geoscientists, they are the best means of determining what Mars looked like eons ago.

Unfortunately for geoscientists, these meteorites have underdone changes as a result of the cataclysmic force that expelled them from Mars. As Dr. Christopher Adcock, an Assistant Research Professor at with the Dept. of Geoscience at UNLV and the lead author of the study, told Universe Today via email:

“Martian meteorites are pieces of Mars, basically they are our only samples of Mars on Earth until there is a sample return mission. Many of the discoveries we have made about Mars came from studying martian meteorites and wouldn’t be possible without them. Unfortunately, these meteorites have all experienced shock from being ejected of the Martian surface during impacts.”

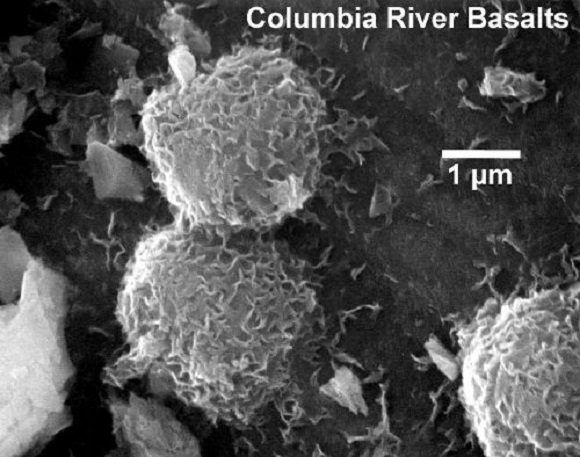

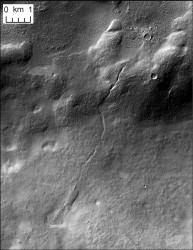

Of the over 100 Martian meteorites that have been retrieved here on Earth, and range in age from between 4 billion years to 165 million years. They are also believed to have come from only a few regions on Mars, and were likely ejecta created from impact events. And in the course of examining them, scientists have noticed the presence of a calcium phosphate mineral known as merrillite.

As a member of the whitlockite group that is commonly found in Lunar and Martian meteorities, this mineral is known for being anhydrous (i.e. containing no water). As such, researchers have drawn the conclusion that the presence of this minerals indicates that Mars had an arid environment when these rocks were ejected. This is certainly consistent with what Mars looks like today – cold, icy and dry as a bone.

For the sake of their study – titled “Shock-Transformation of Whitlockite to Merrillite and the Implications for Meteoritic Phosphate“, which appeared recently in the journal Nature Communications – the international research team considered another possibility. Using a synthetic version of whitlockite, they began conducting shock compression experiments on it designed to simulate the conditions under which meteorites are ejected from Mars.

This consisted of placing the synthetic whitlockite sample inside a projectile, then using a helium gas gun to accelerate it up to speeds of 700 meters per second (2520 km/h or 1500 mph) into a metal plate – thus subjecting it to intense heat and pressure. The sample was then examined using the Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS) and the Argonne National Laboratory’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) instruments.

“When we analyzed what came out of the capsule, we found a significant amount of the whitlockite had dehydrated to the mineral merrillite,” said Adcock. “Merrillite is found in many meteorites (including Martian). The means it is possible the rocks meteorites are made from originally started life with whitlockite in them in an environment with more water than previously thought. If true, it would indicate more water in the Martian past and the early Solar System.”

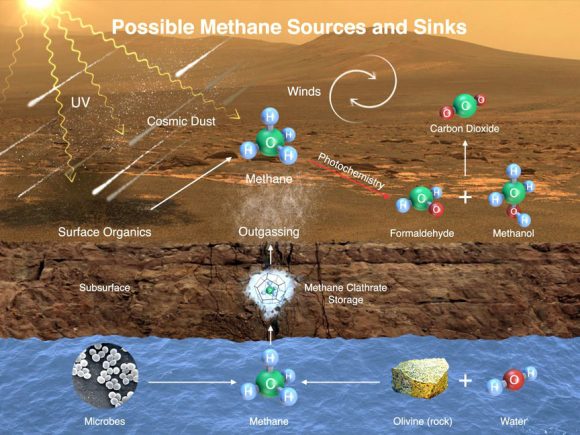

Not only does this find raise the “water budget” for Mars in the past, it also raises new questions about Mars’ habitability. In addition to being soluble in water, whitlockite also contains phosphorous – a crucial element for life here on Earth. Combined with recent evidence that shows that liquid water still exists on Mars’ surface – albeit intermittently – this raises new questions about whether or not Mars had life in the past (or even today).

But as Adcock explained, further experiments and evidence will be needed to determine if these results are indicative of a more watery past:

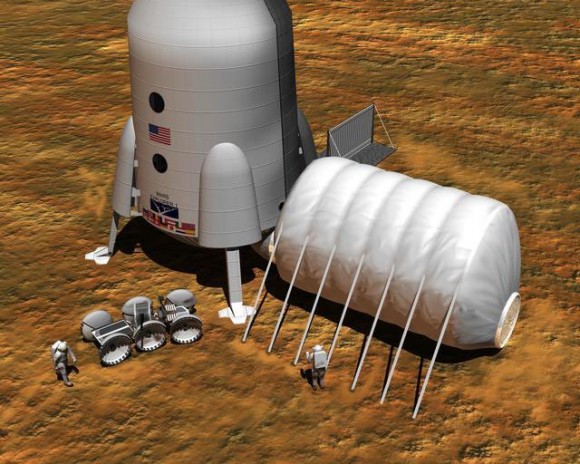

“As far as life goes, our results are very favorable for the possibility – but we need more data. Really we need a sample return mission or we need to go there in person – a human mission. Science is closing in on the answers to a number of big questions about our solar system, life elsewhere, and Mars. But it is difficult work when it all has to be done from far away.”

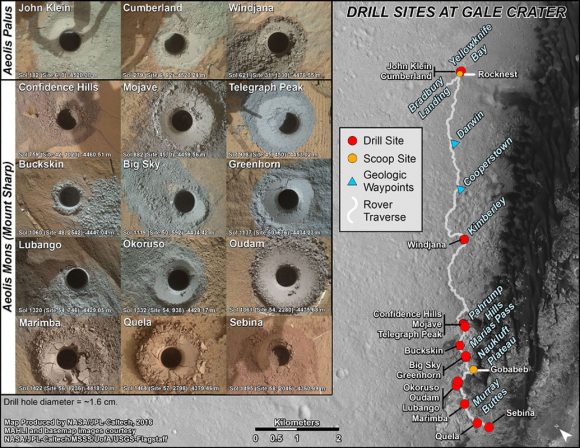

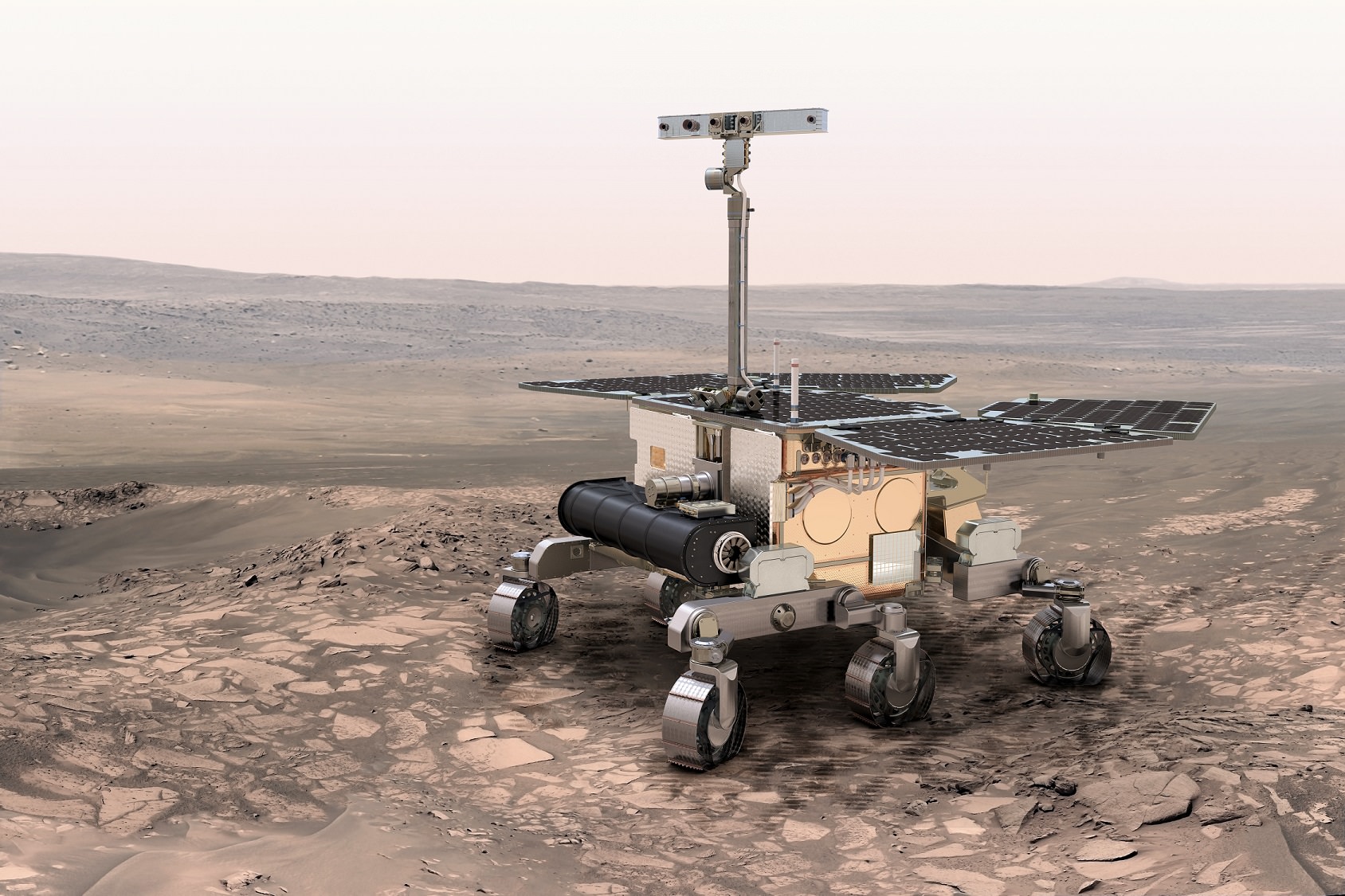

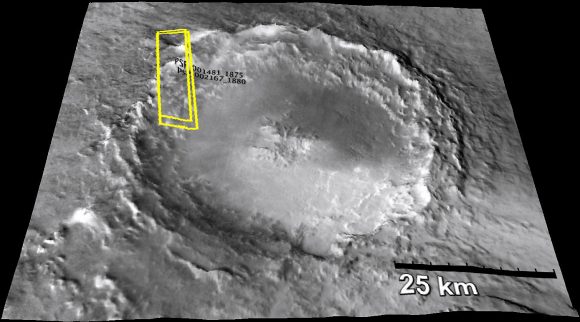

And sample returns are certainly on the horizon. NASA hopes to conduct the first step in this process with their Mars 2020 Rover, which will collect samples and leave them in a cache for future retrieval. The ESA’s ExoMars rover is expected to make the journey to Mars in the same year, and will also obtain samples as part of a sample-return mission to Earth.

These missions are scheduled to launch the summer of 2020, when the planets will be at their closest again. And with crewed missions to the surface planned for the following decade, we might see the first non-meteorite samples of Mars brought back to Earth for analysis.

Further Reading: Nature Communications, Berkeley Lab