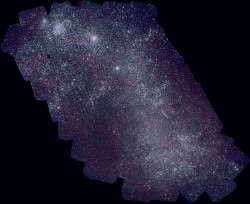

Earth’s galactic next-door neighbors shine brighter than ever in new pictures taken by an orbiting telescope, focusing on ultraviolet light that is tricky to image from the surface.

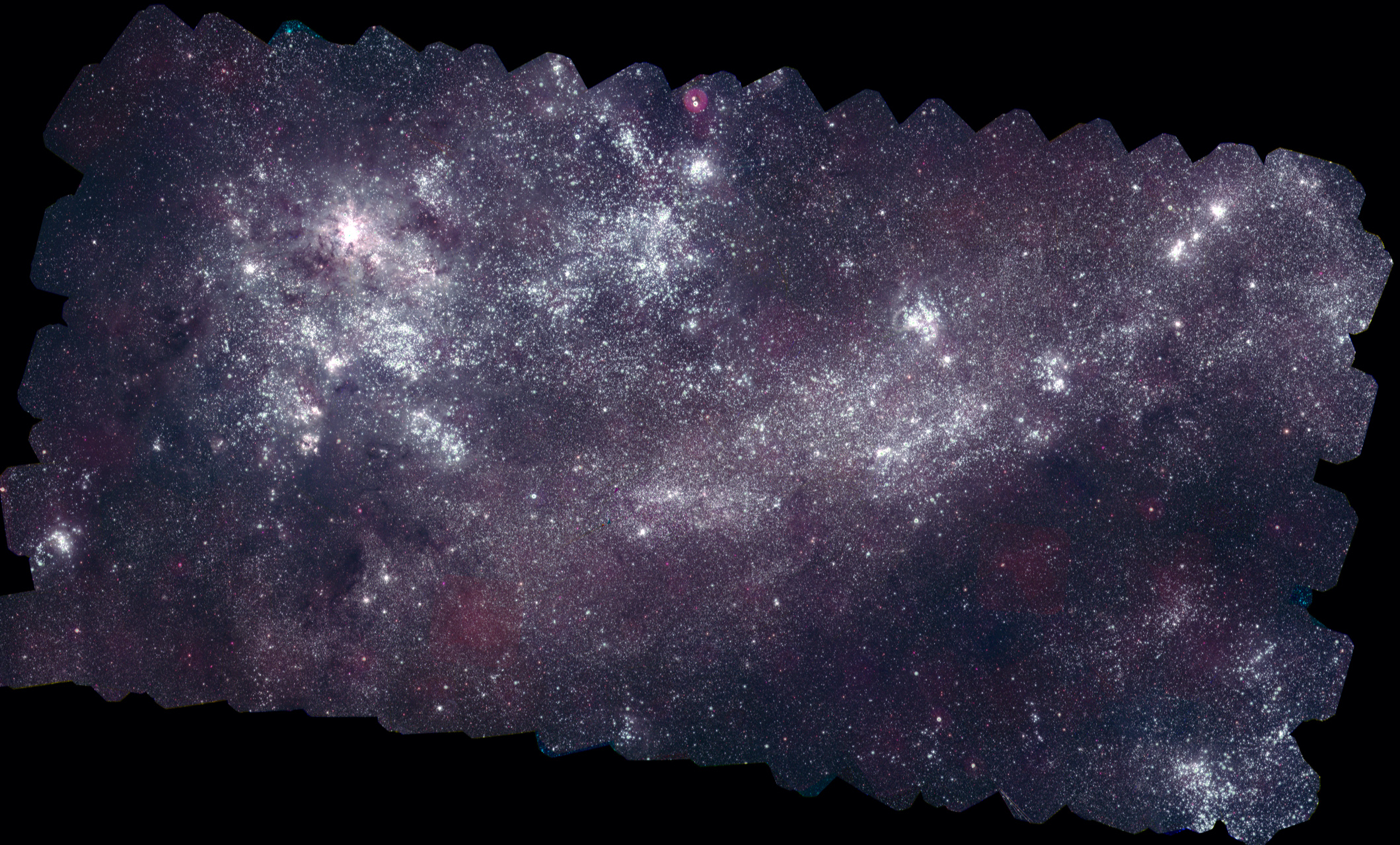

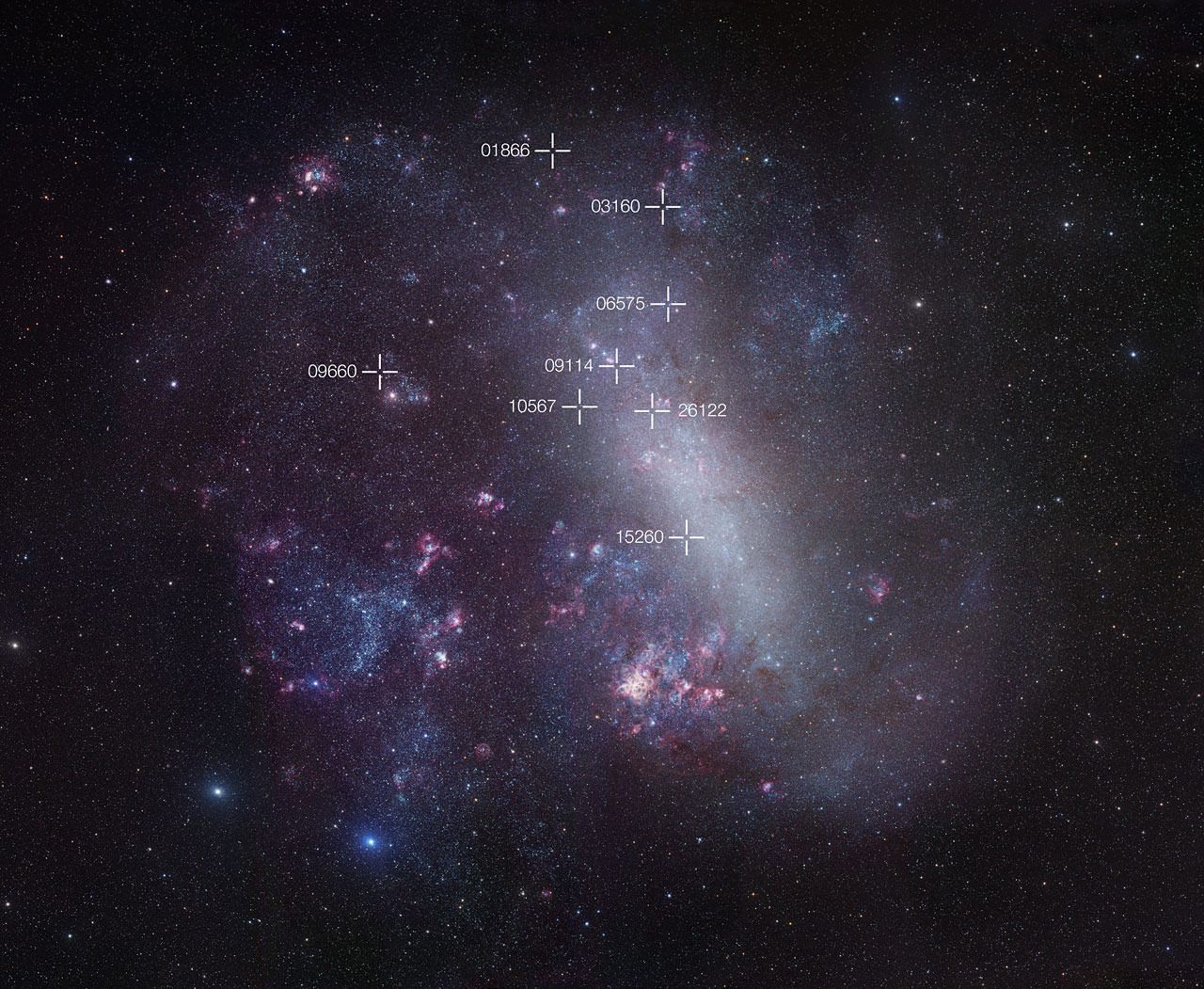

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) and Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) — the two largest major galaxies near our own, the Milky Way — were imaged in 5.4 days and 1.8 days of cumulative exposure time, respectively. These produced two gorgeous, high-resolution photos in a spot of the light spectrum normally invisible to humans.

“Prior to these images, there were relatively few UV observations of these galaxies, and none at high resolution across such wide areas, so this project fills in a major missing piece of the scientific puzzle,” stated Michael Siegel, lead scientist for Swift’s Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope at the Swift Mission Operations Center at Pennsylvania State University.

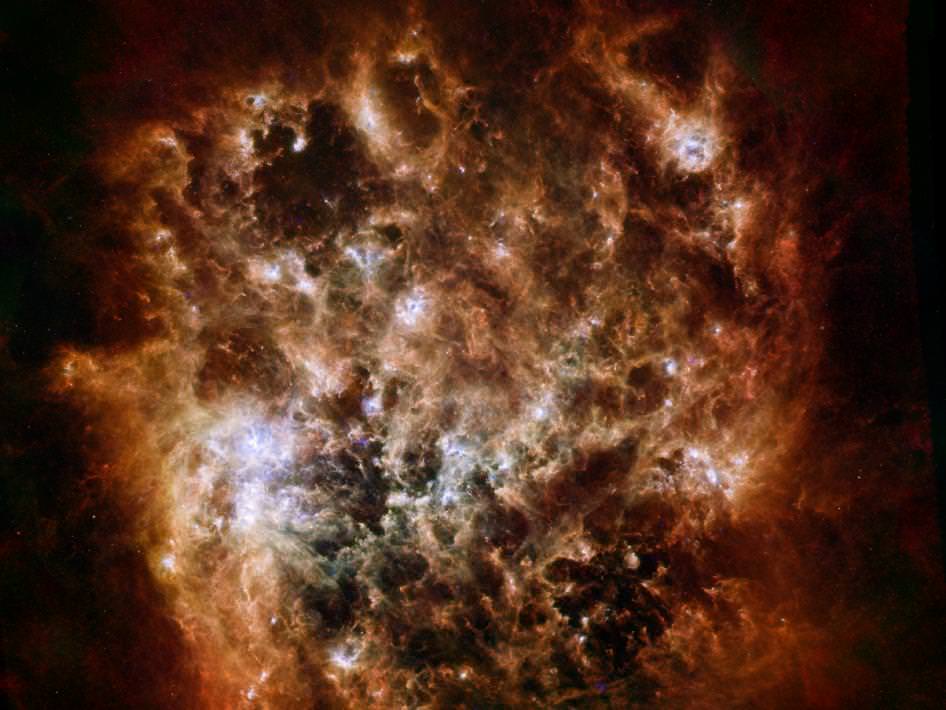

Science isn’t interested in these pictures — taken in wavelengths ranging from 1,600 to 3,300 angstroms, mostly blocked in Earth’s atmosphere — because of their pretty face, however. Ultraviolet light pictures let the hottest stars and star-forming areas shine out, while in visible light those hotspots are suppressed.

“With these mosaics, we can study how stars are born and evolve across each galaxy in a single view, something that’s very difficult to accomplish for our own galaxy because of our location inside it,” stated Stefan Immler, an associate research scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and the lead of the SWIFT guest investigator program.

Although the galaxies are relatively small, they easily shine in our night sky because they’re so close to Earth — 163,000 light-years for the LMC, and 200,000 light years for the SMC.

The LMC is only about 1/10 of the Milky Way’s size, with 1% of the Milky Way’s mass. The punier SMC is half of LMC’s size with only two-thirds of that galaxy’s mass.

Immler revealed the large images — 160 megapixels for the LMC, and 57 megapixels for the SMC — at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Indianapolis on Monday (June 3.)

Source: NASA