Together, the space probes Dawn and New Horizons have been in flight for a collective 17 years. One remained close to home and the other departed to parts of the Solar System of which little is known. They now share a common destination in the same year: dwarf planets.

At the time of these NASA probes’ departures, Ceres had just lost its designation as the largest asteroid in our Solar System. Pluto was the ninth planet. Both probes now stand to deliver measures of new data and insight that could spearhead yet another revision of the definition of planet.

Certainly, NASA’s Year of the Dwarf Planet is an unofficial designation and NASA representatives would be quick to emphasize another dozen or more missions that are of importance during the year 2015. However, these two missions could determine the fate of billions or more small bodies just within our galaxy, the Milky Way.

If Ceres and Pluto are studied up close – mission success is never a sure thing – then what is observed could lead to a new, more certain and accepted definition of planet, dwarf planet, and possibly other new definitions.

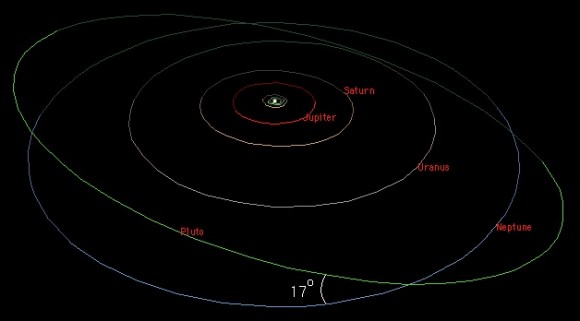

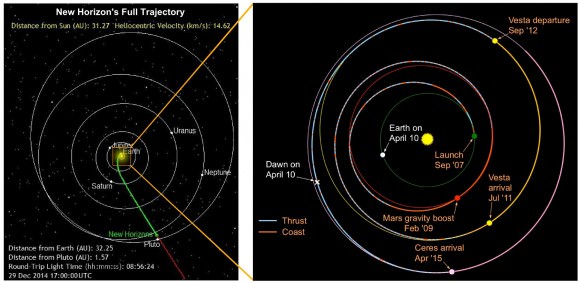

The New Horizons mission became the first mission of NASA’s New Frontiers program, beginning development in 2001. The probe was launched on January 19, 2006, atop an Atlas V 551 (5 solid rocket boosters plus a third stage). Utilizing more compact and lightweight electronics than its predecessors to the outer planets – Pioneer 10 & 11, and Voyager 1 & 2 – the combination of reduced weight, a powerful launch vehicle, plus a gravity assist from Jupiter has lead to a nine year journey. On December 6, 2014, New Horizons was taken out of hibernation for the last time and now remains powered on until the Pluto encounter.

The arrival date of New Horizon is July 14, 2015. A telescope called the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) has permitted the commencement of observations while still over 240 million kilometers (150 million miles) from Pluto. The first stellar-like images were taken while still in the Asteroid belt in 2006.

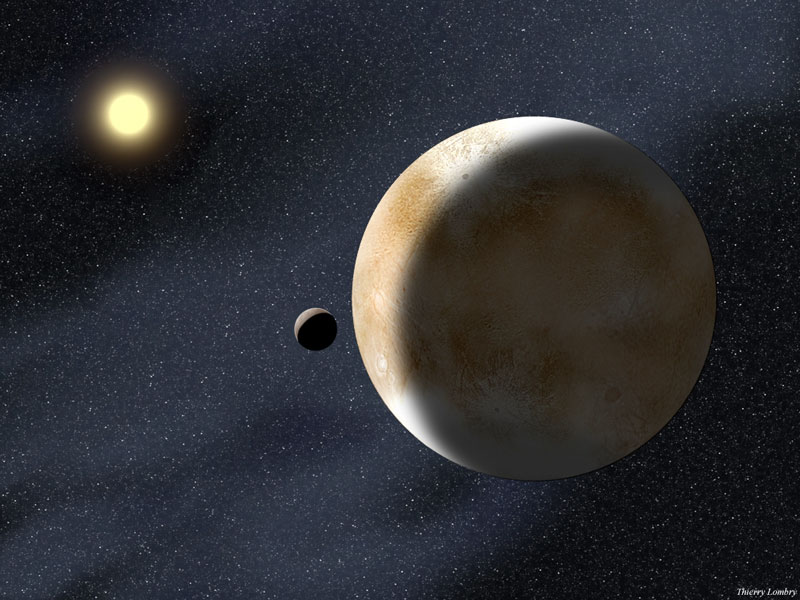

Pluto was once the ninth planet of the Solar System. From its discovery in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh until 2006, it maintained this status. In that latter year, the International Astronomical Union undertook a debate and then a membership vote that redefined what a planet is. The change occurred 8 months after New Horizons’ launch. There were some upset mission scientists, foremost of which was the principal investigator, Dr. Alan Stern, from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas. In a sense, the rug had been pulled from under them.

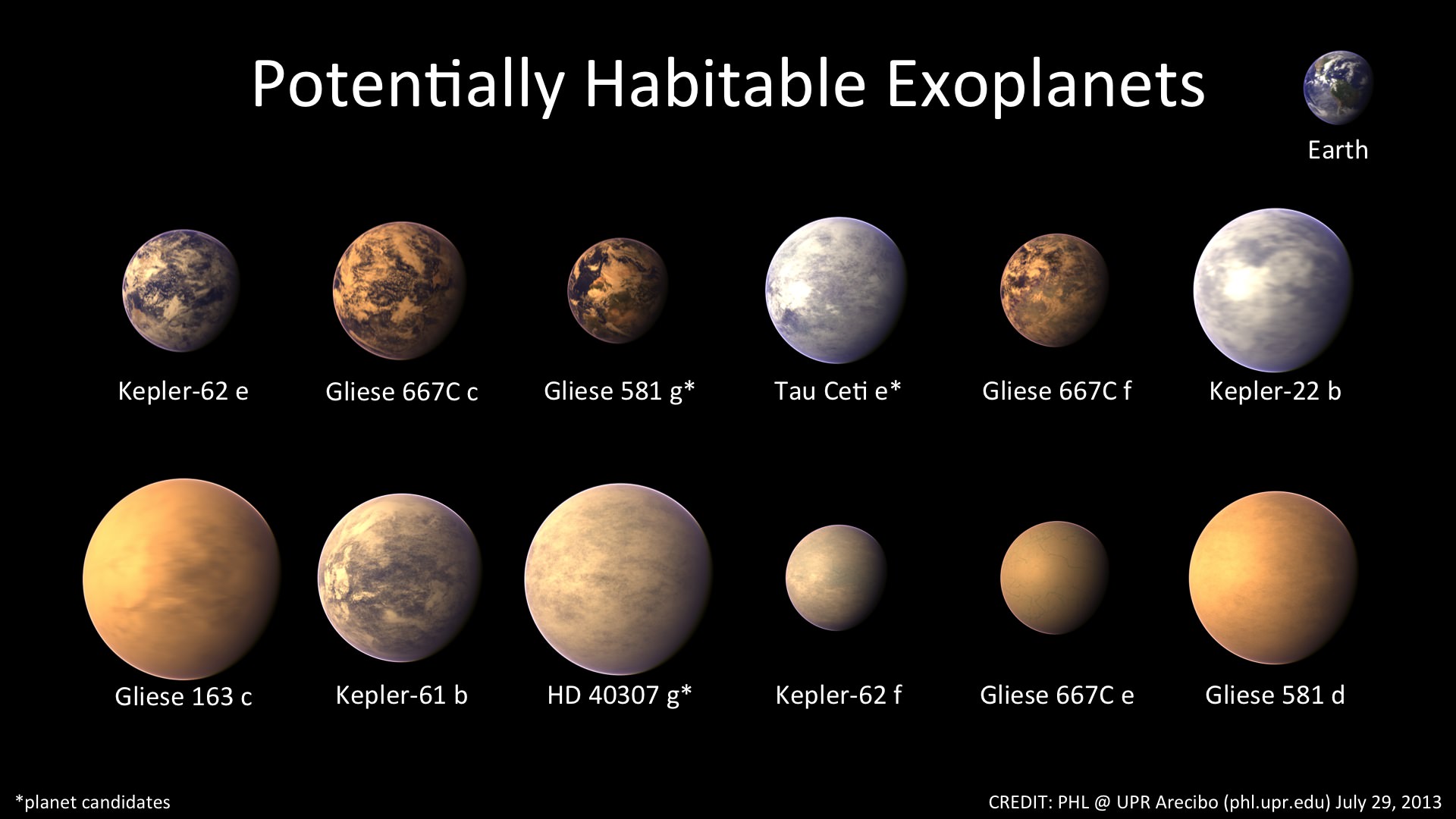

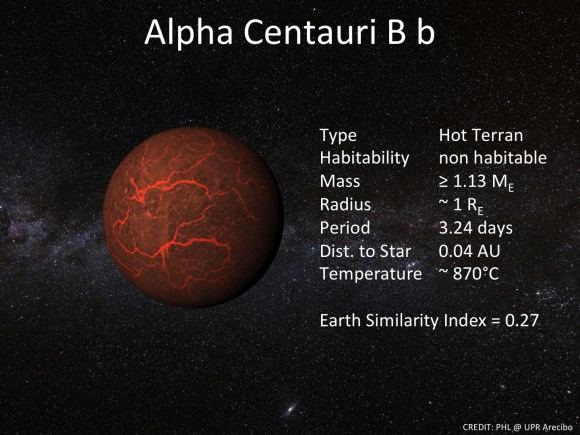

A gentleman’s battle ensued between opposing protagonists Dr. Stern and Dr. Michael Brown from Caltech. In 2001, Dr. Brown’s research team began to discover Kuiper belt objects (Trans-Neptunian objects) that rivaled the size of Pluto. Pluto suddenly appeared to be one of many small bodies that could likely number in the trillions within just one galaxy – ours. According to Dr. Brown, there could be as many as 200 objects in our Solar System similar to Pluto that, under the old definition, could be defined as planets. Dr. Brown’s work was the straw that broke the camel’s back – that is, it led to the redefinition of planet, and the native of Huntsville, Alabama, went on to write a popular book, How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming.

Dr. Stern’s story involving Pluto and planetary research is a longer and more circuitous one. Stern was the Executive Director of the Southwest Research Institute’s Space Science and Engineering Division and then accepted the position of Associate Administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in 2007. Clearly, after a nine year journey, Stern is now fully committed to New Horizons’ close encounter. More descriptions of the two protagonists of the Pluto debate will be included in a follow on story.

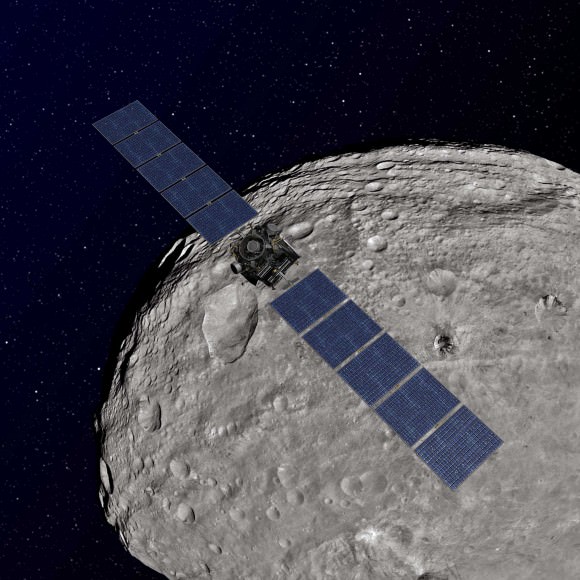

The JPL and Orbital Science Corporation developed Dawn space probe began its journey to the main asteroid belt on September 27, 2007. It has used gravity assists and flew by the planet Mars. Dawn spent 14 months surveying Vesta, the 4th largest asteroid of the main belt (assuming Ceres is still considered the largest). While New Horizons has traveled over 30 Astronomical Units (A.U.) – 30 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun – Dawn has remained closer and required reaching a little over 2 A.U. to reach Vesta and now 3 A.U. to reach Ceres.

The Dawn mission had the clear objective of rendezvous and achieving orbit with two asteroids in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter. Dawn was also sent packing the next generation of Ion Propulsion. It has proven its effectiveness very well, having used ion propulsion for the first time to achieve an orbit. Pretty simple, right? Not so fast.

As Dawn was passing critical design reviews during development, the redefinition of planet lofted its second objective – the asteroid 1 Ceres – to a new status. While Pluto was demoted, Ceres was promoted from its scrappy status of biggest of the asteroids – the debris, the leftovers of our solar system’s development – to dwarf planet. Even 4 Vesta is now designated a proto-planet.

So now the stage is set. Dawn will arrive first at a dwarf planet – Ceres – in April. With a small, low gravity body and ion propulsion, the arrival is slow and cautious. If the two missions fair well and achieve their goals, 2015 is likely to become a pivotal year in the debate over the classification of non-stellar objects throughout the universe.

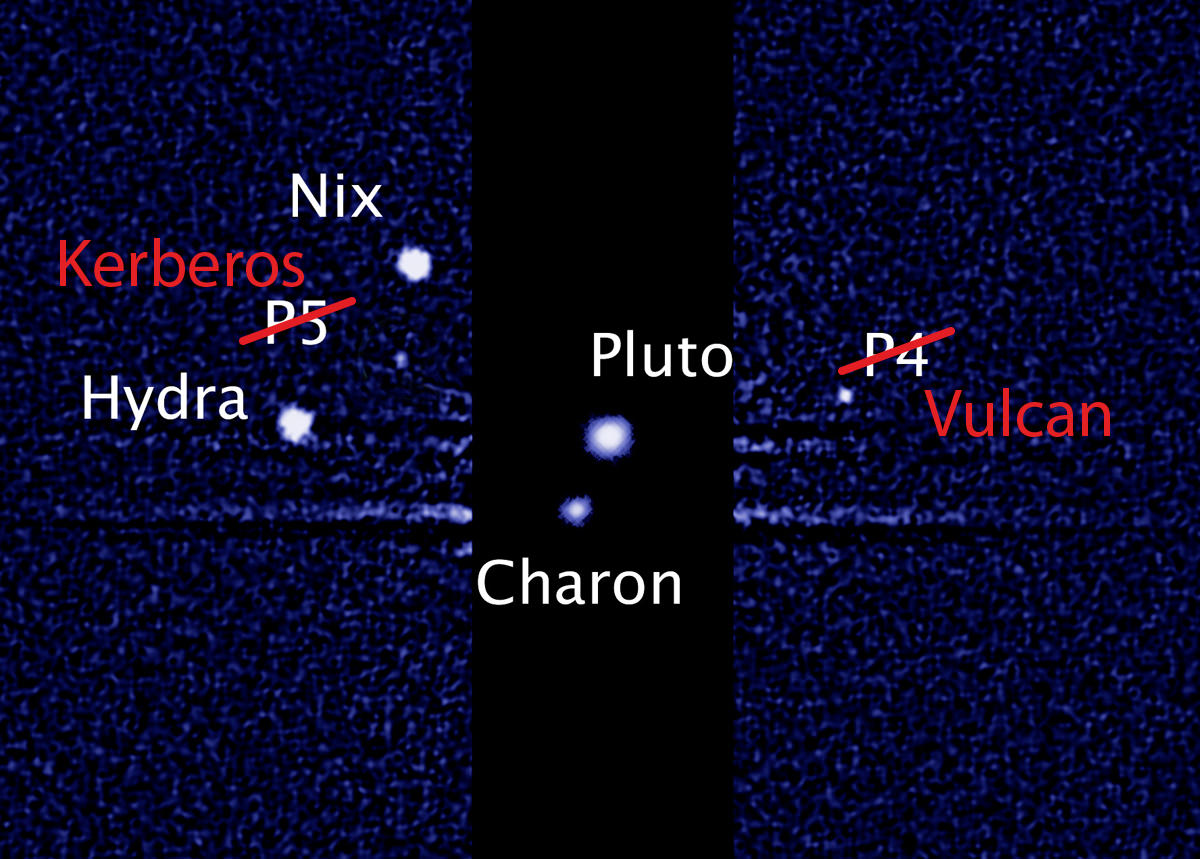

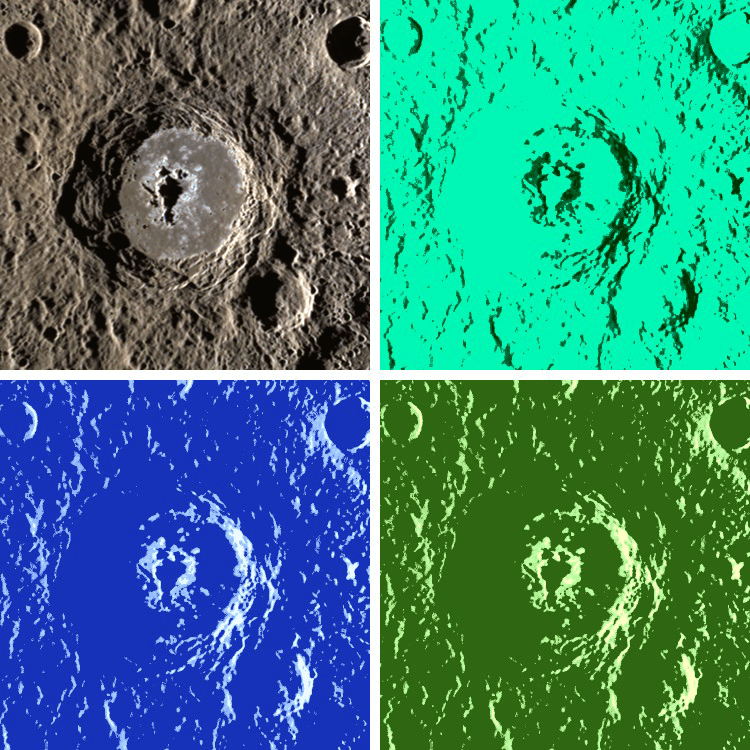

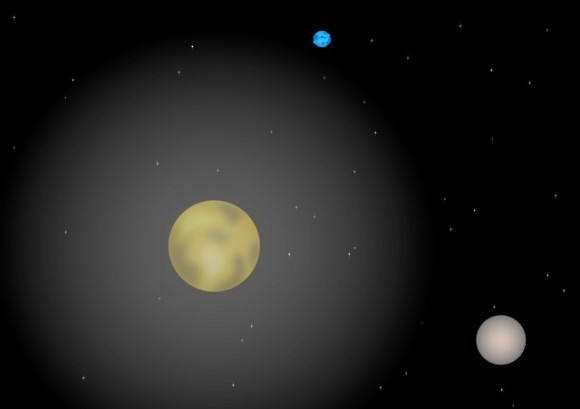

Just days ago, at the American Geophysical Union Conference in San Francisco, Dr. Stern and team described the status and more details of the goals of New Horizons. Since arriving, more moons of Pluto have been discovered. There is the potential that faint rings exist and Pluto may even harbor an interior ocean due to the tidal forces from its largest moon, Charon. And Dawn mission scientists have seen the prospects for Ceres’ change. Not just the status, the latest Hubble images of Ceres is showing bright spots which could be water ice deposits and could also harbor an internal ocean.

So other NASA missions notwithstanding, this is the year of the dwarf planet. NASA will provide Humanity with its first close encounters with the most numerous of small round – by their self-gravity – bodies in the Universe. They are now called dwarf planets but ask Dr. Stern and company, the public, and many other planetary scientists and you will discover that the jury is still out.

References:

JHU/APL New Horizons Mission Home Page

Related Universe Today articles: