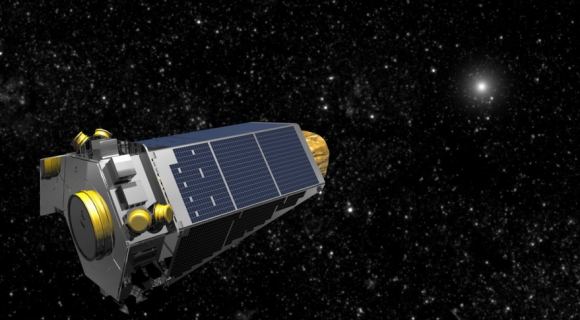

Ever since it was deployed in March of 2009, the Kepler mission has detected thousands of extra-solar planet candidates. In fact, between 2009 and 2012, it detected a total of 4,496 candidates, and confirmed the existence of 2,337 exoplanets. Even after two of its reaction wheels failed, the spacecraft still managed to turn up distant planets as part of its K2 mission, accounting for another 521 candidates and confirming 157.

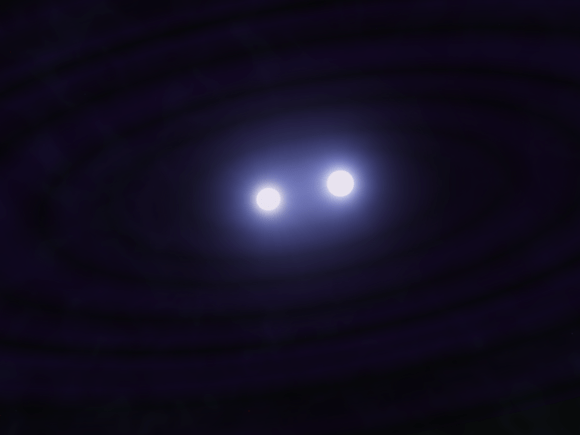

However, according to a new study conducted by a pair of researches from Columbia University and a citizen scientist, Kepler may also have also found evidence of an extra-solar moon. After sifting through data from hundreds of transits detected by the Kepler mission, the researchers found one instance where a transiting planet showed signs of having a satellite.

Their study – which recently published online under the title “HEK VI: On the Dearth of Galilean Analogs in Kepler and the Exomoon Candidate Kepler-1625b I” – was by led Alex Teachey, a graduate student at Columbia University and a Graduate Research Fellow with the National Science Foundation (NSF). He was joined by David Kipping, an Assistant Professor of Astronomy at Columbia University and the Principal Investigator of The Hunt for Exomoons with Kepler (HEK) project, and Allan Schmitt, a citizen scientist.

For years, Dr. Kipping has been searching the Kepler database for evidence of exomoons, as part of the HEK. This is not surprising, considering the kinds of opportunities that exomoons present for scientific research. Within our Solar System, the study of natural satellites has revealed important things about the mechanisms that drive early and late planet formation, and moons possess interesting geological features that are commonly found on other bodies.

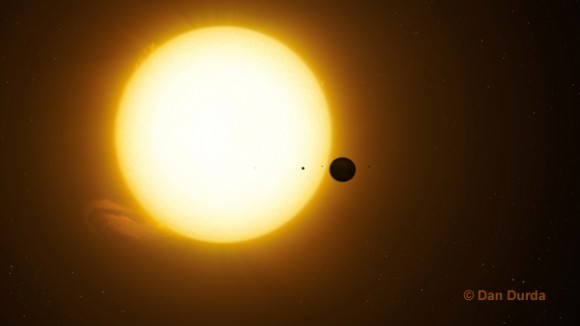

It is for this reason that extending that research to the hunt for exoplanets is seen as necessary. Already, exoplanet-hunting missions like Kepler have turned up a wealth of planets that challenge conventional ideas about how planet formation and what kinds of planets are possible. The most noteworthy example are gas giants that have observed orbiting very close to their stars (aka. “Hot Jupiters”).

As such, the study of exomoons could yield valuable information about what kinds of satellites are possible, and whether or not our own moons are typical. As Teachey told Universe Today via email:

“Exomoons could tell us a lot about the formation of our Solar System, and other star systems. We see moons in our Solar System, but are they common elsewhere? We tend to think so, but we can’t know for sure until we actually see them. But it’s an important question because, if we find out there aren’t very many moons out there, it suggests maybe something unusual was going on in our Solar System in the early days, and that could have major implications for how life arose on the Earth. In other words, is the history of our Solar System common across the galaxy, or do we have a very unusual origin story? And what does that say about the chances of life arising here? Exomoons stand to offer us clues to answering these questions.”

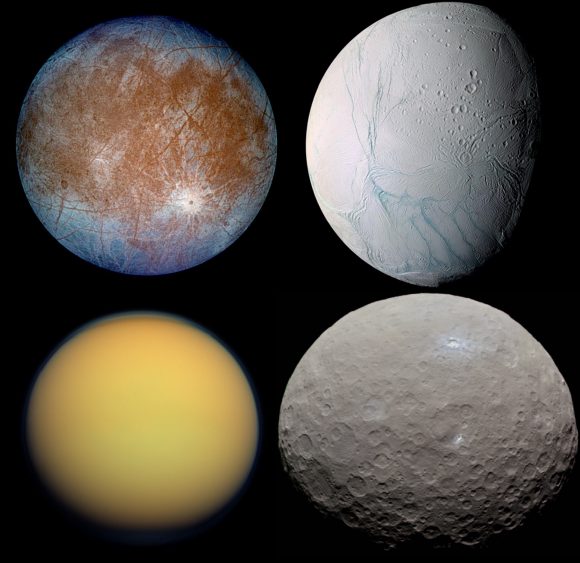

What’s more, many moons in the Solar System – including Europa, Ganymede, Enceladus and Titan – are thought to be potentially habitable. This is due to the fact that these bodies have steady supplies of volatiles (such as nitrogen, water, carbon dioxide, ammonia, hydrogen, methane and sulfur dioxide) and possess internal heating mechanisms that could provide the necessary energy to power biological processes.

Here too, the study of exomoons presents interesting possibilities, such as whether or not they may be habitable or even Earth-like. For these and other reasons, astronomers want to see if the planets that have been confirmed in distant star systems have systems of moons and what conditions are like on them. But as Teachey indicated, the search for exomoons presents a number of challenges compared to exoplanet-hunting:

“Moons are difficult to find because 1) we expect them to be quite small most of the time, meaning the transit signal will be quite weak to begin with, and 2) every time a planet transits, the moon will show up in a different place. This makes them more difficult to detect in the data, and modeling the transit events is significantly more computationally expensive. But our work leverages the moons showing up in different places by taking the time-averaged signal across many different transit events, and even across many different exoplanetary systems. If the moons are there, they will in effect carve out a signal on either side of the planetary transit over time. Then it’s a matter of modeling this signal and understanding what it means in terms of moon size and occurrence rate.”

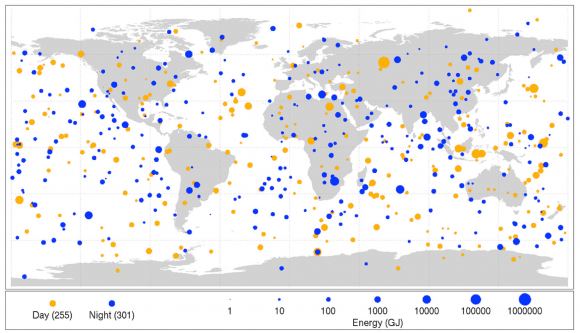

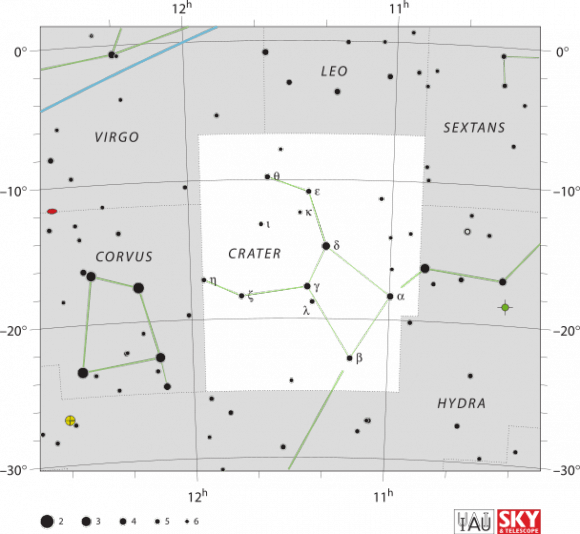

To locate signs of exomoons, Teachey and his colleagues searched through the Kepler database and analyzed the transits of 284 exoplanet candidates in front of their respective stars. These planets ranged in size from being Earth-like to Jupiter-like in diameter, and orbited their stars at a distance of between ~0.1 to 1.0 AU. They then modeled the light curve of the stars using the techniques of phase-folding and stacking.

These techniques are commonly used by astronomers who monitor stars for dips in luminosity that are caused by the transits of planets (i.e. the transit method). As Teachey explained, the process is quite similar:

“Basically we cut up the time-series data into equal pieces, each piece having one transit of the planet in the middle. And when we stack these pieces together we’re able to get a clearer picture of what the transit looks like… For the moon search we do essentially the same thing, only now we’re looking at the data outside the main planetary transit. Once we stack the data, we take the average values of all the data points within a certain time window and, if a moon is present, we ought to see some missing starlight there, which allows us to deduce its presence.”

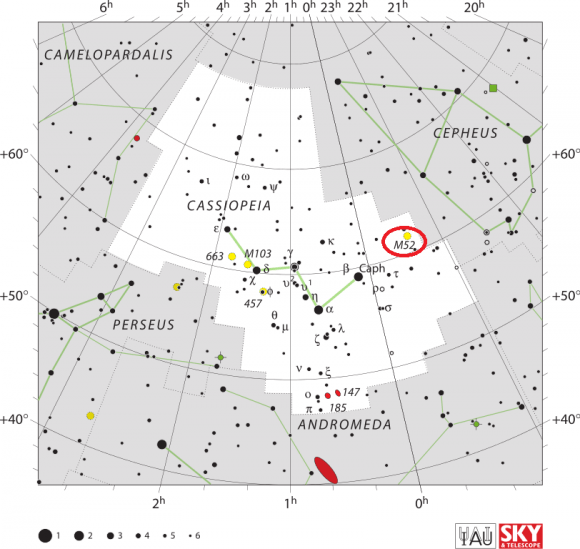

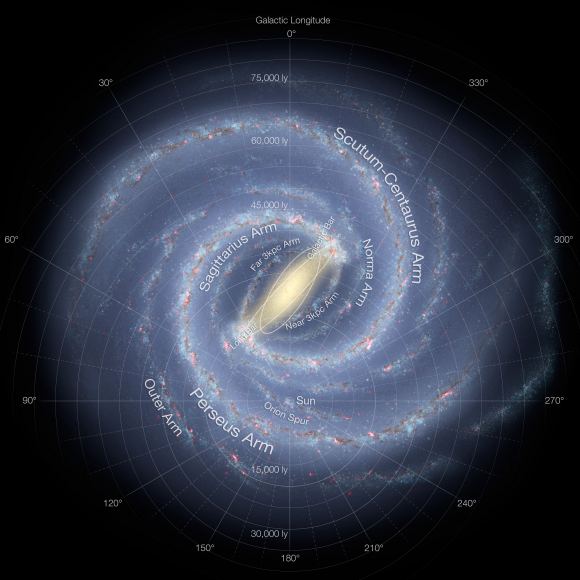

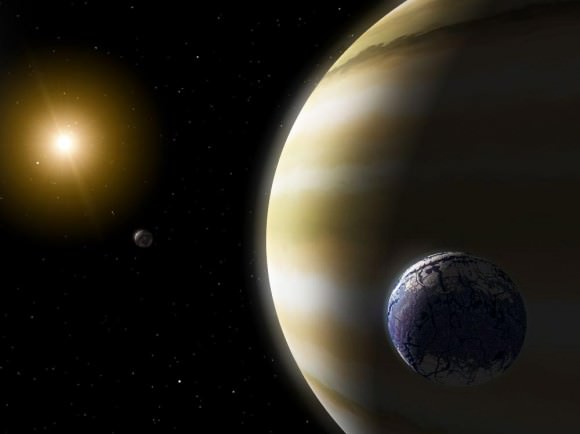

What they found was a single candidate located in the Kepler-1625 system, a yellow star located about 4000 light years from Earth. Designated Kepler-1625B I, this moon orbits the large gas giant that is located within the star’s habitable zone, is 5.9 to 11.67 times the size of Earth, and orbits its star with a period of 287.4 days. This exomoon candidate, if it should be confirmed, will be the first exomoon ever discovered

The team’s results (which await peer review) also demonstrated that large moons to be a rare occurrence in the inner regions of star systems (within 1 AU). This was something of a surprise, though Teachey acknowledges that it is consistent with recent theoretical work. According to what some recent studies suggest, large planets like Jupiter could lose their moons as they migrate inward.

If this should prove to be the case, then what Teachey and his colleagues witnessed could be seen as evidence of that process. It could also be an indication our current exoplanet-hunting missions may not be up to the task of detecting exomoons. In the coming years, next-generations missions are expected to provide more detailed analyses of distant stars and their planetary systems.

However, as Teachey indicated, these too could be limited in terms of what they can detect, and new strategies may ultimately be needed:

“The rarity of moons in the inner regions of these star systems suggests that individual moons will remain difficult to find in the Kepler data, and upcoming missions like TESS, which should find lots of very short period planets, will also have a difficult time finding these moons. It’s likely the moons, which we still expect to be out there somewhere, reside in the outer regions of these star systems, much as they do in our Solar System. But these regions are much more difficult to probe, so we will have to get even more clever about how we look for these worlds with present and near-future datasets.”

In the meantime, we can certainly be exited about the fact that the first exomoon appears to have been discovered. While these results await peer review, confirmation of this moon will mean additional research opportunities for Kepler-1625 system. The fact that this moon orbits within the star’s habitable zone is also an interesting feature, though its not likely the moon itself is habitable.

Still, the possibility of a habitable moon orbiting a gas giant is certainly interesting. Does that sound like something that might have come up in some science fiction movies?

Further Reading: arXiv