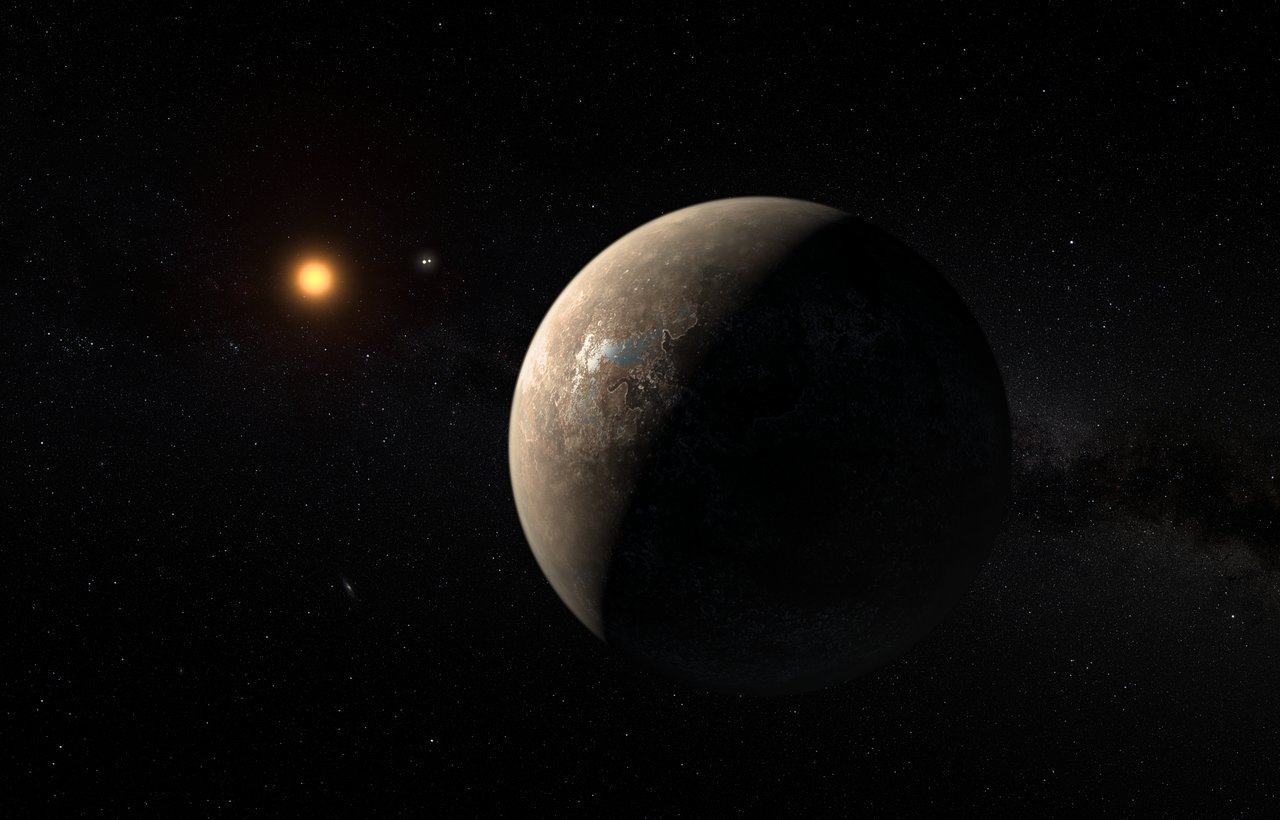

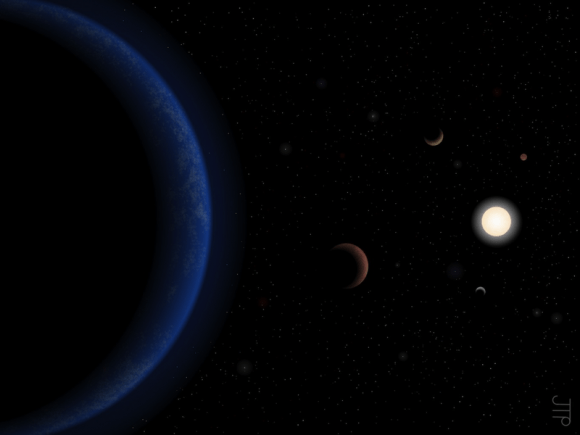

It has been an exciting time for the field of exoplanet studies lately! Last summer, researchers from the European Southern Observatory (ESO) announced the discovery of an Earth-like planet (Proxima b) located in the star system that is the nearest to our own. And just six months ago, an international team of astronomers announced the discovery of seven rocky planets orbiting the nearby star TRAPPIST-1.

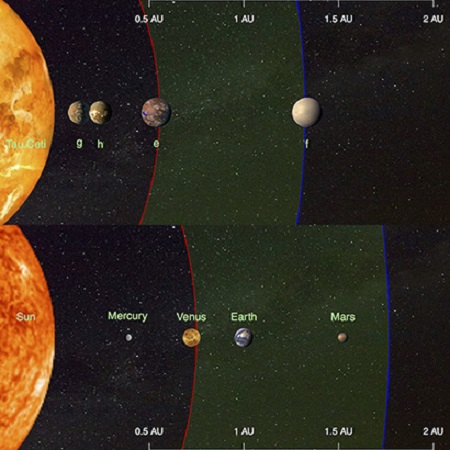

But in what could be the most encouraging discovery for those hoping to find a habitable planet beyond Earth, an an international team of astronomers just announced the discovery of four exoplanet candidates in the tau Ceti system. Aside from being close to the Solar System – just 12 light-years away – this find is also encouraging because the planet candidates orbit a star very much like our own!

The study that details these findings – “Color difference makes a difference: four planet candidates around tau Ceti” – recently appeared online and has been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal. Led by researchers from the Center for Astrophysics Research (CAR) at the University of Hertfordshire, the team analyzed tau Ceti using a noise-eliminating model to determine the presence of four Earth-like planets.

This discovery was made possible thanks to ongoing improvements in instrumentation, observation and data-sharing, which are allowing for surveys of ever-increasing sensitivity. As Steven Vogt, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UC Santa Cruz and a co-author on the paper, said in a UCSC press release:

“We are now finally crossing a threshold where, through very sophisticated modeling of large combined data sets from multiple independent observers, we can disentangle the noise due to stellar surface activity from the very tiny signals generated by the gravitational tugs from Earth-sized orbiting planets.”

This is the latest in a long-line of surveys of tau Ceti, which has been of interest to astronomers for decades. By 1988, several radial velocity measurements were conducted of the star system that ruled out the possibility of massive planets at Jupiter-like distances. In 2012, astronomers from UC Santa Barabara presented a study that indicated that tau Ceti might be orbited by five exoplanets, two of which were within the star’s habitable zone.

The team behind that study included several members who produced this latest study. At the time, lead author Mikko Tuomi (University of Hertfordshire, a co-author on the most recent one) was leading an effort to develop better data analysis techniques, and used this star as a benchmark case. As Tuomi explained, theses efforts allowed them to rule out two of the signals that has previously been identified as planets:

“We came up with an ingenious way of telling the difference between signals caused by planets and those caused by star’s activity. We realized that we could see how star’s activity differed at different wavelengths and use that information to separate this activity from signals of planets.”

For the sake of this latest study – which was led by Fabo Feng, a member of the CAR – the team relied on data provided by the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) spectrograph at the ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile, and the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES) instrument at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Mauna Kea, Hawaii.

From this, they were able to create a model that removed “wavelength dependent noise” from radial velocity measurements. After applying this model to surveys made of tau Ceti, they were able to obtain measurements that were sensitive enough to detect variations in the star’s movement as small as 30 cm per second. In the end, they concluded that tau Ceti has a system of no more than four exoplanets.

As Tuomi indicated, after several surveys and attempts to eliminate extraneous noise, astronomers may finally have a clear picture of how many planets tau Ceti has, and of what type. “[N]o matter how we look at the star, there seem to be at least four rocky planets orbiting it,” he said. “We are slowly learning to tell the difference between wobbles caused by planets and those caused by stellar active surface. This enabled us to essentially verify the existence of the two outer, potentially habitable planets in the system.”

They further estimate from their refined measurements that these planets have masses ranging from four Earth-masses (aka. “super-Earths”) to as low as 1.7 Earth masses, making them among the smallest planets ever detected around a nearby sun-like star. But most exciting of all is the fact that that two of these planets (tau Ceti e and f) are located within the star’s habitable zone.

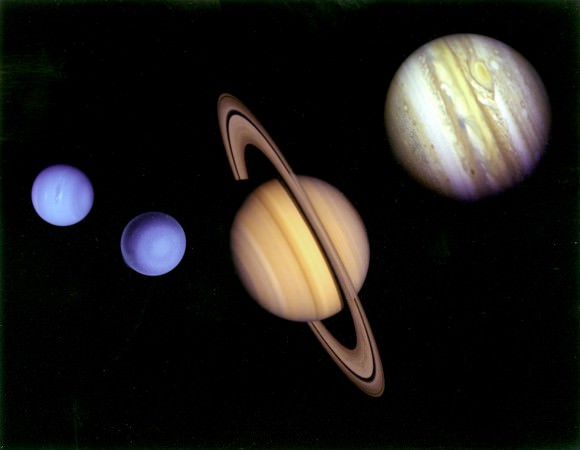

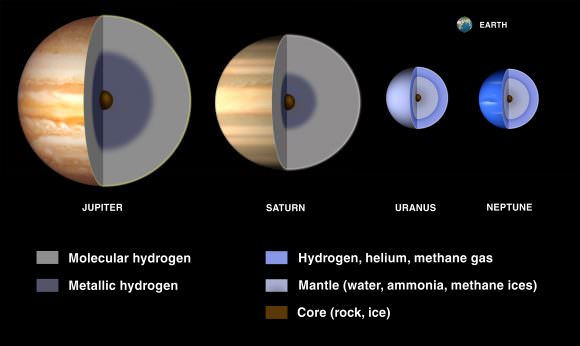

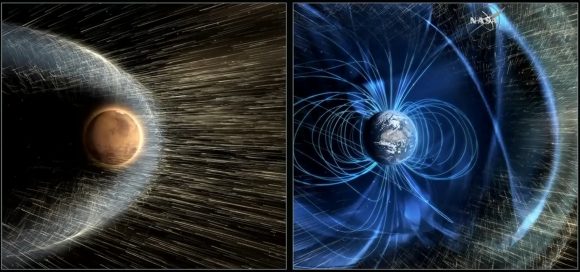

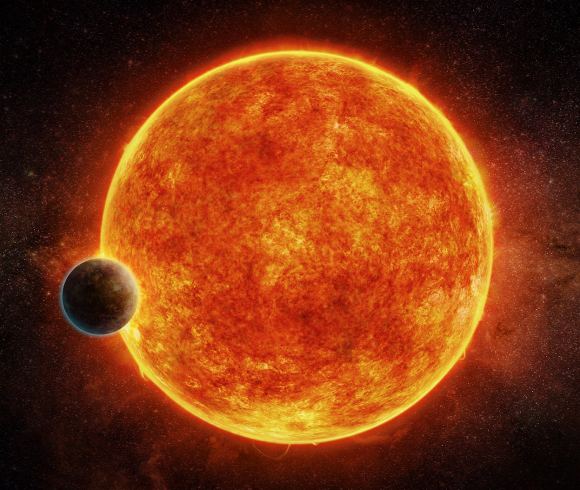

The reason for this is because tau Ceti is a G-type (yellow dwarf) star, which makes it similar to our own Sun – about 0.78 times as massive and half as bright. In contrast, many recently discovered exoplanets – such as Proxima b and the seven planets of TRAPPIST-1 – all orbit M-type (red dwarf) stars. Compared to our Sun, these stars are variable and unstable, increasing their chances of stripping the atmospheres of their respective planets.

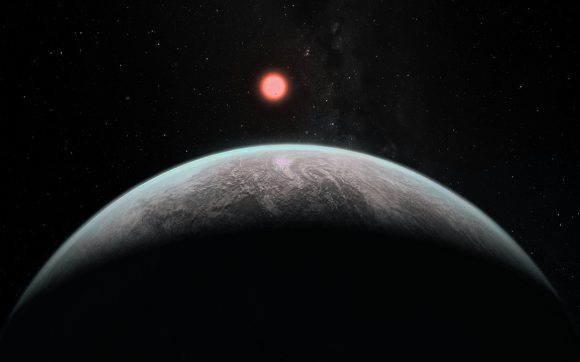

In addition, since red dwarfs are much dimmer than our Sun, a rocky planet would have to orbit very closely to them in order to be within their habitable zones. At this kind of distance, the planet would likely be tidally-locked, meaning that one side would constantly be facing towards the sun. This too makes the odds of life emerging on any such planet pretty slim.

Because of this, astronomers have been looking forward to finding more exoplanets around stars that are closer in size, mass and luminosity to our own. But before anyone gets too excited, its important to note these worlds are Super-Earths – with up to four times the mass of Earth. This means that (depending on their density as well) any life that might emerge on these planets would be subject to significantly increased gravity.

In addition, a massive debris disc surrounds the star, which means that these outermost planets are probably subjected to intensive bombardment by asteroids and comets. This not doesn’t exactly bode well for potential life on these planets! Still, this study is very encouraging, and for a number of reasons. Beyond finding strong evidence of exoplanets around a Sun-like star, the measurements that led to their detection are the most sensitive to date.

At the rate that their methods are improving, researchers should be getting to the 10-centimeter-per-second limit in no time at all. This is the level of sensitively required for detecting Earth analogs – aka. the brass ring for exoplanet-hunters. As Feng indicated:

“Our detection of such weak wobbles is a milestone in the search for Earth analogs and the understanding of the Earth’s habitability through comparison with these analogs. We have introduced new methods to remove the noise in the data in order to reveal the weak planetary signals.”

Think of it! In no time at all, exoplanet-hunters could be finding a plethora of planets that are not only very close in size and mass to Earth, but also orbiting within their stars habitable zones. At that point, scientists are sure to dispense with decidedly vague terms like “potentially habitable” and “Earth-like” and begin using terms like “Earth-analog” confidently. No more ambiguity, just the firm conviction that Earth is not unique!

With an estimated 100 billion planets in our galaxy alone, we’re sure to find several Earths out here. One can only hope they have given rise to complex life like our own, and that they are in the mood to chat!