ISS astronauts Barry “Butch” Wilmore, NASA, Samantha Cristoforetti, ESA and Terry Virts, NASA send Christmas 2014 greetings from the space station to the people of Earth. Credit: NASA/ESA

Story/pics expanded. Send holiday tweet to crew below![/caption]

There is a long tradition of Christmas greetings from spacefarers soaring around the High Frontier and this year is no exception!

The Expedition 42 crew currently serving aboard the International Space Station has decorated the station for the Christmas 2014 holiday season and send their greetings to all the people of Earth from about 240 miles (400 km) above!

“Merry Christmas from the International Space Station!” said astronauts Barry Wilmore and Terry Virts of NASA and Samantha Cristoforetti of ESA, who posed for the group shot above.

“It’s beginning to look like Christmas on the International Space Station,” said NASA in holiday blog update.

“The stockings are out, the tree is up and the station residents continue advanced space research to benefit life on Earth and in space.”

And the six person crew including a trio of Russian cosmonauts, Aleksandr Samokutyayev, Yelena Serova, and Anton Shkaplerov who celebrate Russian Orthodox Christmas, are certainly hoping for and encouraging a visit from Santa. Terry Virts even tweeted a picture of the special space style milk and cookies awaiting Santa and his Reindeer for the imminent arrival!

“No chimney up here- so I left powdered milk and freeze dried cookies in the airlock. Fingers crossed,” tweeted Virts.

And here’s a special Christmas video greeting from Wilmore and Virts:

Video Caption: Aboard the International Space Station, Expedition 42 Commander Barry Wilmore and Flight Engineer Terry Virts of NASA offered their thoughts and best wishes to the world for the Christmas holiday during downlink messages from the orbital complex on Dec. 17. Wilmore has been aboard the research lab since late September and will remain in orbit until mid-March 2015. Virts arrived at the station in late November and will stay until mid-May 2015. Credit: NASA

“We wish you all a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year. Christmas for us is a time of worship. It’s a time that we think back to the birth of what we consider our Lord. And we do that in our homes and we plan to do the same thing up here and take just a little bit of time just to reflect on those topics and, also, just as the Wise Men gave gifts, we have a couple of gifts,” Wilmore says in the video.

“It’s such an honor and so much fun to be able to celebrate Christmas up here. This is definitely a Christmas that we’ll remember, getting a chance to see the beautiful Earth,” added Virts. “Have fun with your family. Merry Christmas!”

And you can send a holiday tweet to the crew – here:

Meanwhile the crew is still hard at work doing science and preparing for the next space station resupply mission launch by SpaceX from Cape Canaveral, Florida.

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket is now set to blastoff on Jan. 6, 2015 carrying the Dragon cargo freighter on the CRS-5 mission bound for the ISS.

The launch was postponed from Dec. 19 when a static fire test of the first stage engines on Dec. 17 shut down prematurely.

A second static fire test of the SpaceX Falcon 9 went the full duration and cleared the path for the Jan. 6 liftoff attempt.

Among the science studies ongoing according to NASA are:

“Behavioral testing for the Neuromapping study to assess changes in a crew member’s perception, motor control, memory and attention during a six-month space mission. Results will help physicians understand brain structure and function changes in space, how a crew member adapts to returning to Earth and develop effective countermeasures.”

“Another study is observing why human skin ages at a quicker rate in space than on Earth. The Skin B experiment will provide scientists a model to study the aging of other human organs and help future crew members prepare for long-term missions beyond low-Earth orbit.”

Merry Christmas to All!

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

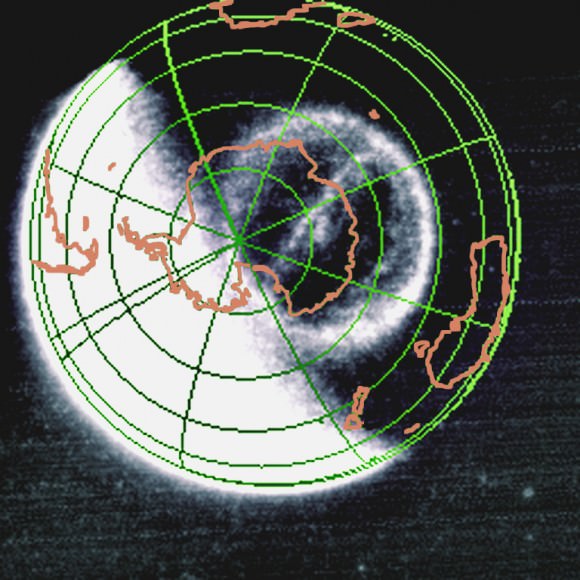

![A video of an observed major geomagnetic storm (July 15, 2000) taken by the Far Ultraviolet Imaging System (FUV) on IMAGE. IMAGE operated from 2000 to December 2005 when communications were lost. (Credit: NASA/SWRI) [click to view the animated gif]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/IMAGE_Aurora-200007151-580x461.gif)