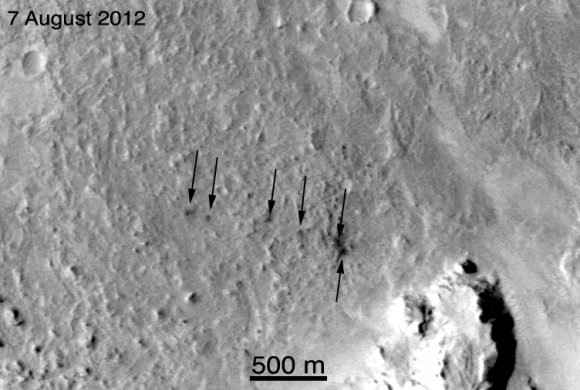

The Moon’s a very dusty museum where the exhibits haven’t changed much over the last 4 billion years. Or so we thought. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has provided researchers strong evidence the Moon’s volcanic activity slowed gradually instead of stopping abruptly a billion years ago.

Some volcanic deposits are estimated to be 100 million years old, meaning the moon was spouting lava when dinosaurs of the Cretaceous era were busy swatting giant dragonflies. There are even hints of 50-million-year-old volcanism, practically yesterday by lunar standards.

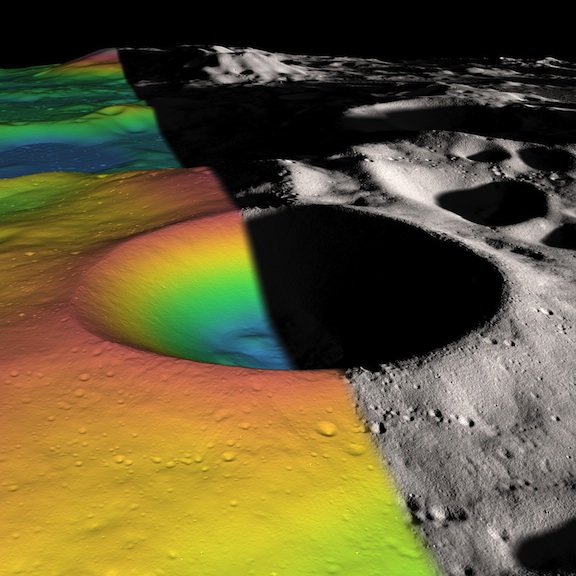

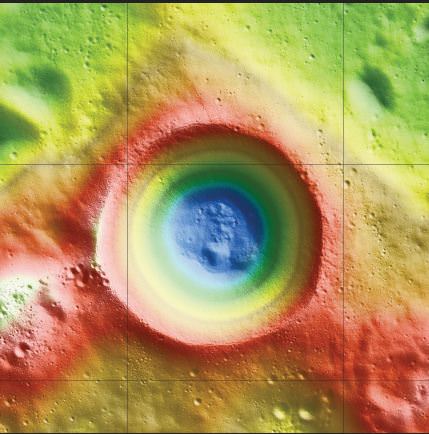

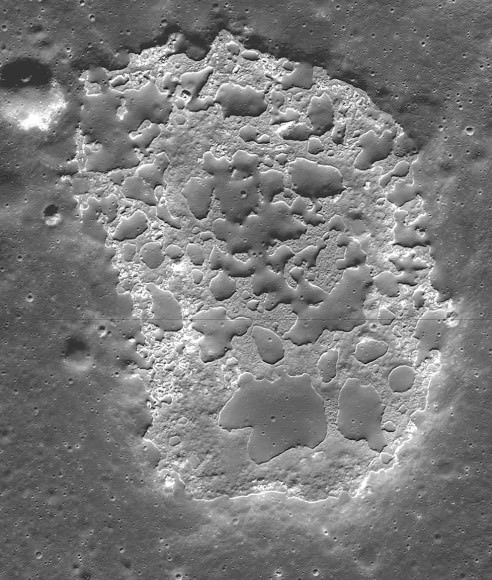

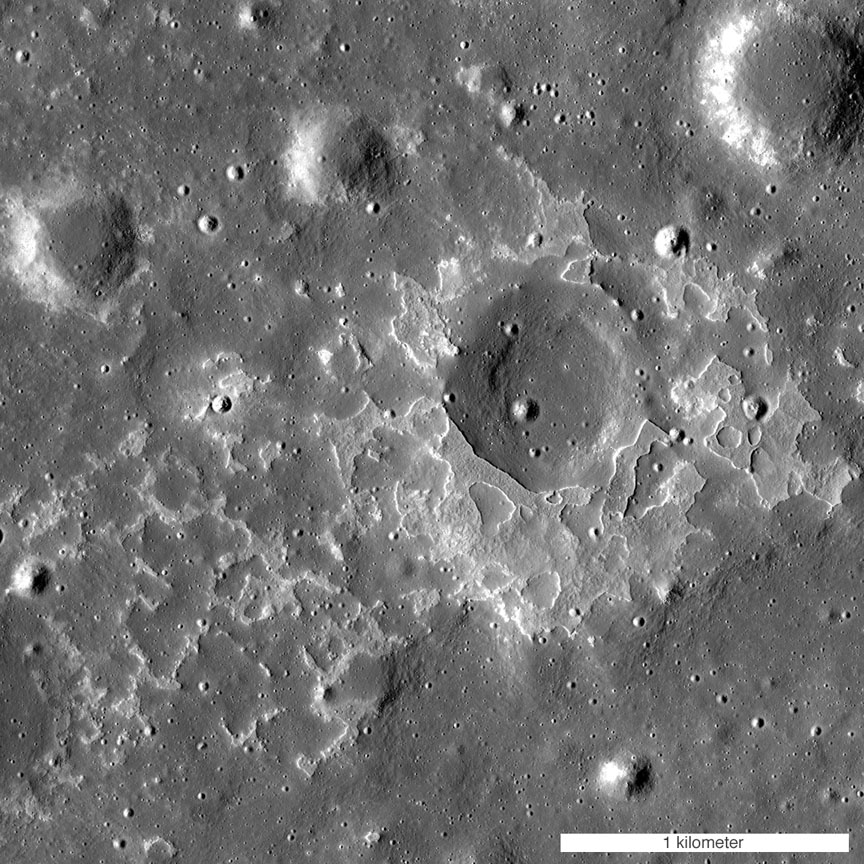

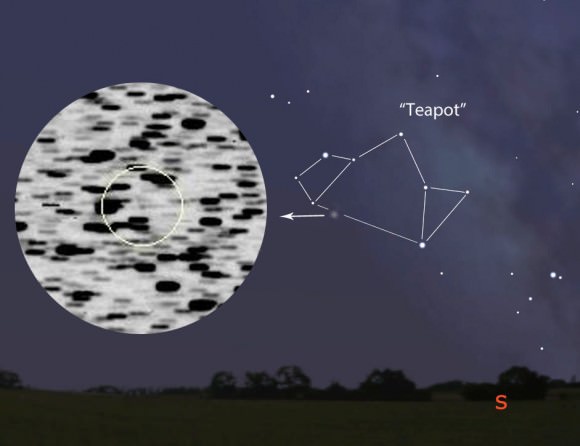

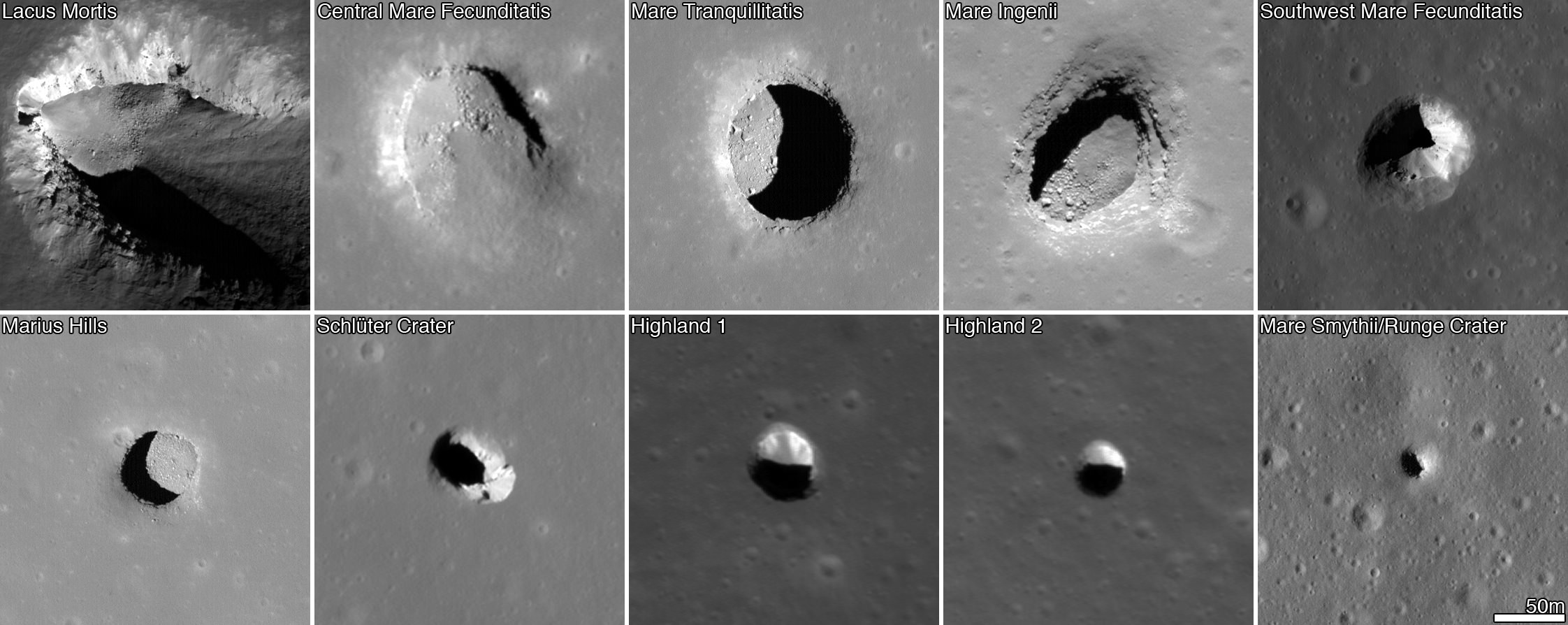

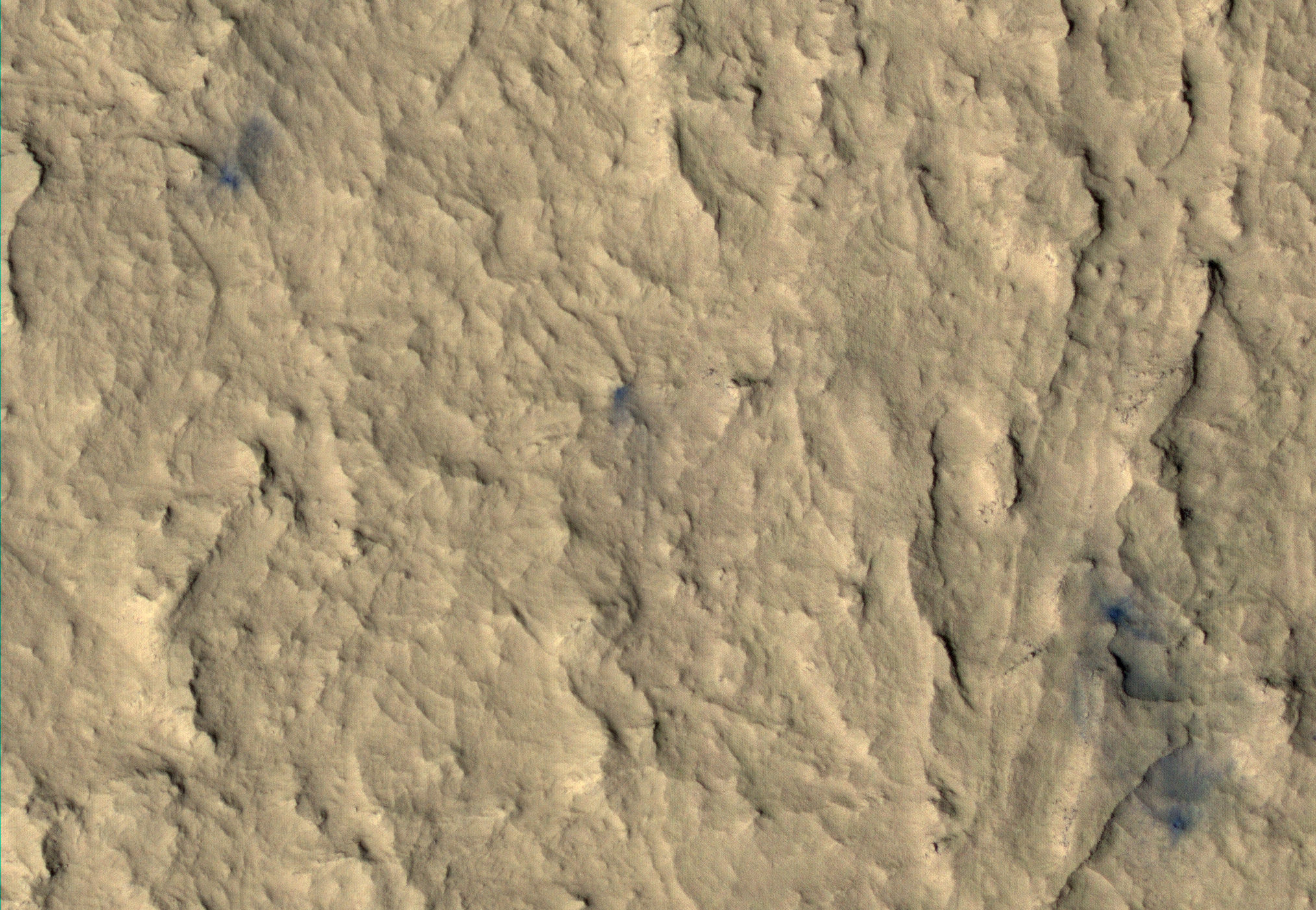

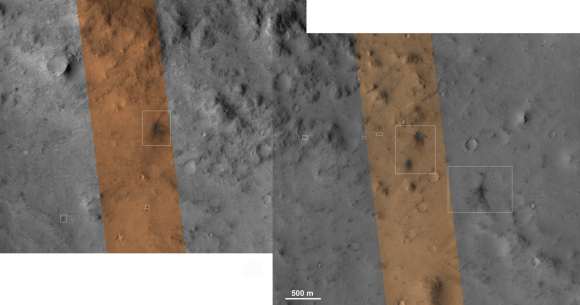

The deposits are scattered across the Moon’s dark volcanic plains (lunar “seas”) and are characterized by a mixture of smooth, rounded, shallow mounds next to patches of rough, blocky terrain. Because of this combination of textures, the researchers refer to these unusual areas as “irregular mare patches.”

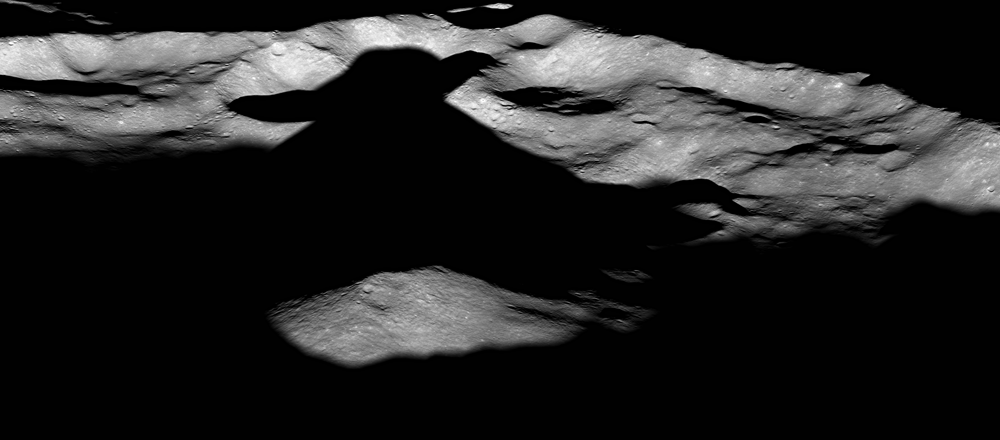

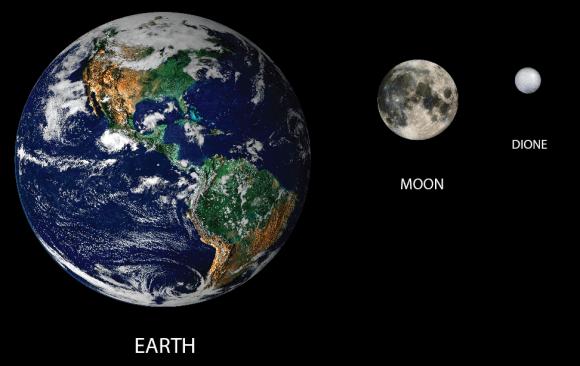

Measuring less than one-third mile (1/2 km) across, almost all are too small to see from Earth with the exception of Ina Caldera, a 2-mile-long D-shaped patch where blobs of older, crater-pitted lunar crust (darker blobs) rise some 250 feet above the younger, rubbly surface like melted cheese on pizza.

Ina was thought to be a one-of-a-kind until researchers from Arizona State University in Tempe and Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster in Germany spotted 70 more patches in close-up photos taken by the LRO. The large number and the fact that the patches are scattered all over the nearside of the Moon means that volcanic activity was not only recent but widespread.

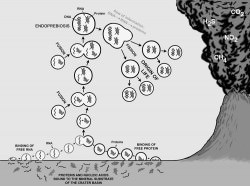

Astronomers estimate ages for features on the moon by counting crater numbers and sizes (the fewer seen, the younger the surface) and the steepness of the slopes running from the tops of the smoother domes to the rough terrain below (the steeper, the younger).

“Based on a technique that links such crater measurements to the ages of Apollo and Luna samples, three of the irregular mare patches are thought to be less than 100 million years old, and perhaps less than 50 million years old in the case of Ina,” according to the NASA press release.

The young mare patches stand in stark contrast to the ancient volcanic terrain surrounding them that dates from 3.5 to 1 billion years ago.

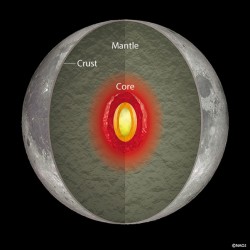

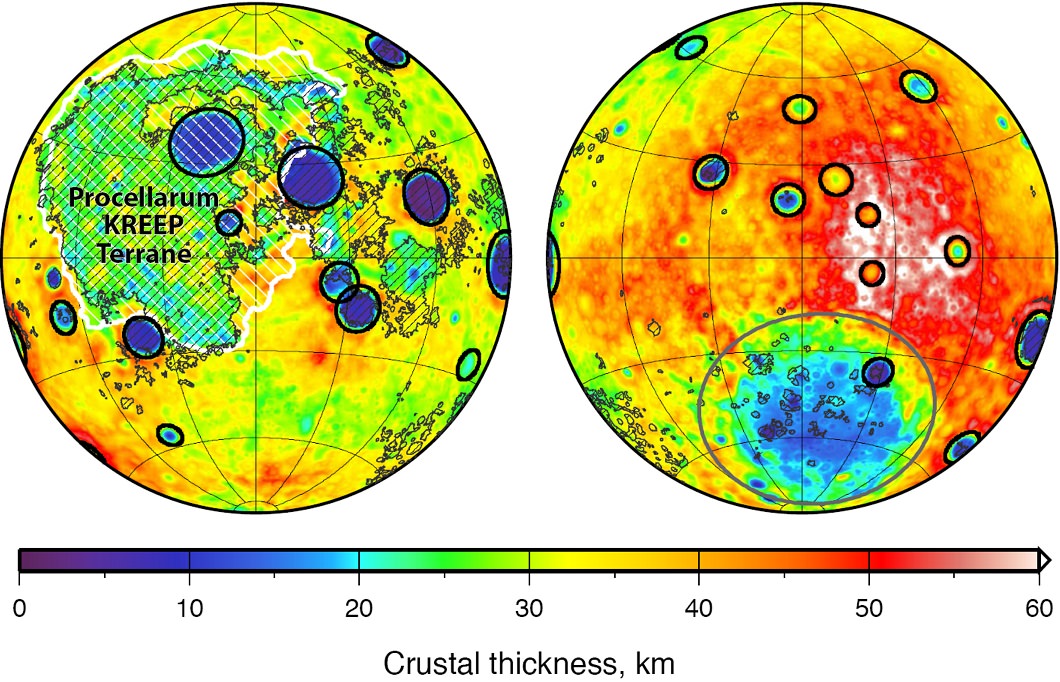

For lava to flow you need a hot mantle, the deep layer of rock beneath the crust that extends to the Moon’s metal core. And a hot mantle means a core that’s still cranking out a lot of heat.

Scientists thought the Moon had cooled off a billion or more years ago, making recent flows all but impossible. Apparently the moon’s interior remained piping hot far longer than anyone had supposed.

“The existence and age of the irregular mare patches tell us that the lunar mantle had to remain hot enough to provide magma for the small-volume eruptions that created these unusual young features,” said Sarah Braden, a recent Arizona State University graduate and the lead author of the study.

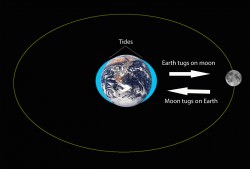

One way to keep the Moon warm is through tidal interaction with the Earth. A recent study points out that strains caused by Earth’s gravitational tug on the Moon (nearside vs. farside) heats up its interior. Could this be the source of the relatively recent lava flows?

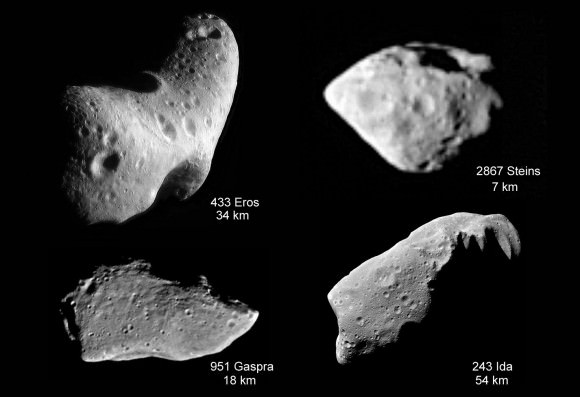

So the pendulum swings. Prior to 1950 it was thought that lunar craters and landforms were all produced by volcanic activity. But the size and global distribution of craters – and the volcanoes required to produce them – would be impossible on a small body like the Moon. In the 1950s and beyond, astronomers came to realize through the study of nuclear bomb tests and high-velocity impact experiments that explosive impacts from asteroids large and small were responsible for the Moon’s craters.

This latest revelation gives us a more nuanced view of how volcanism may continue to play a role in the formation of lunar features.

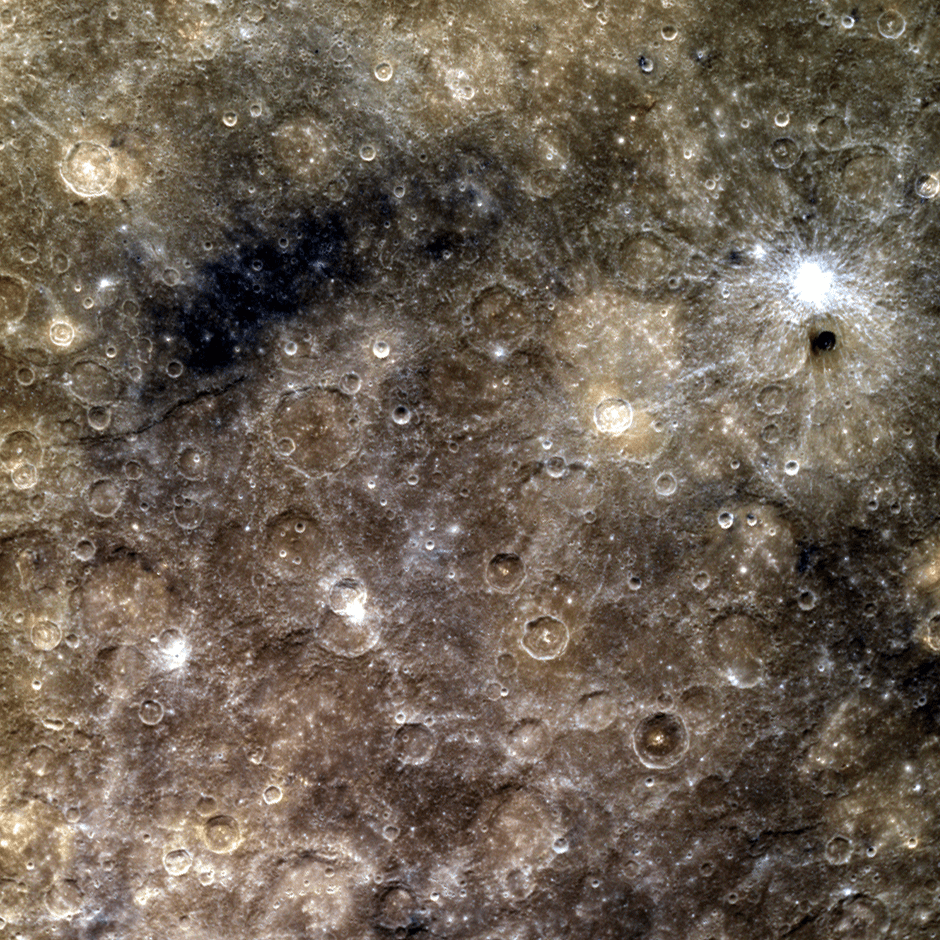

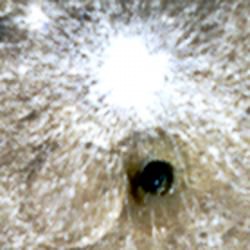

This scene lies between Mercury’s Moody and Amaral craters, spanning an area of about 1200 km (745 miles). The patch of dark blue Low Reflectance Material (LRM) in the upper left of the image and the bright rayed crater on the right make this a diverse view of Mercury’s surface. Note the curious small, dark crater just below the bright rayed crater on the right.

This scene lies between Mercury’s Moody and Amaral craters, spanning an area of about 1200 km (745 miles). The patch of dark blue Low Reflectance Material (LRM) in the upper left of the image and the bright rayed crater on the right make this a diverse view of Mercury’s surface. Note the curious small, dark crater just below the bright rayed crater on the right.