Inspired by SETI Chief, Jill Tarter’s 2009 TED ‘Prize Wish’ to “Empower Earthlings everywhere to become active participants in the ultimate search for cosmic company” the Energetic Ray Global Observatory or ERGO is an exciting new to project that aims to enlist students around the world to turn our whole planet into one massive cosmic-ray telescope to detect the energetic charged particles that arrive at Earth from space. Find out how it works and how your school can get involved Continue reading “ERGO – Students Sign up to Build the World’s Largest Telescope!”

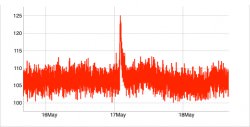

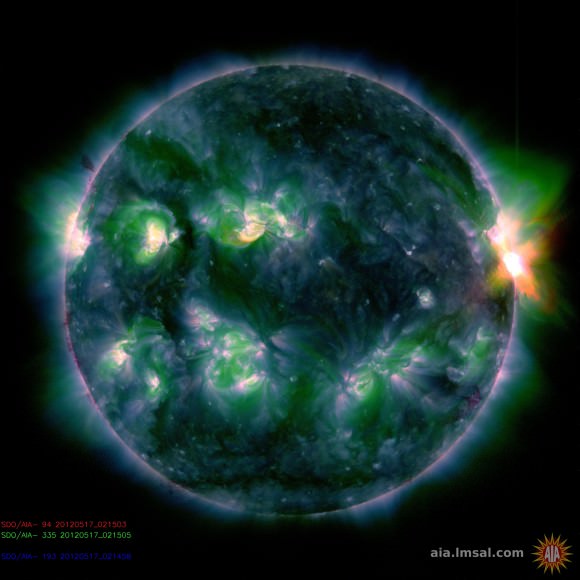

A Rare Type of Solar Storm Spotted by Satellite

[/caption]

When a moderate-sized M-class flare erupted from the Sun on May 17, it sent out a barrage of high-energy solar particles that belied its initial intensity. These particles traveled at nearly the speed of light, crossing the 93 million miles between the Sun and Earth in a mere 20 minutes and impacting our atmosphere, causing cascades of neutrons to reach the ground — a rare event known as a ground level enhancement, or GLE.

The first such event since 2006, the GLE was recorded by a joint Russian/Italian spacecraft called PAMELA and is an indicator that the peak of solar maximum is on the way.

The PAMELA spacecraft — which stands for Payload for Antimatter-Matter Exploration and Light-nuclei Astrophysics — is designed to detect high-energy cosmic rays streaming in from intergalactic space. But on May 17, scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center convinced the Russian team in charge of PAMELA to grab data from the solar event occurring much closer to home.

The result: the first observations from space of the solar particles that trigger the neutron storms that make up a GLE. Scientists hope to use the data to learn more about how GLEs are created, and why the May 17 “moderate” solar flare ended up making one.

“Usually we would expect this kind of ground level enhancement from a giant coronal mass ejection or a big X-class flare,” said Georgia de Nolfo, a space scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. “So not only are we really excited that we were able to observe these particularly high energy particles from space, but we also have a scientific puzzle to solve.”

Fewer than 100 GLEs have been recorded in the last 70 years, with the most powerful having occurred on February 23, 1956. Like most energetic solar outbursts, GLEs can have disruptive effects on sensitive electronics in orbit as well as on the ground, and based on recent studies may even have adverse effects on cellular systems and development.

Read more on the NASA news release here.

Cosmic Rays: They Aren’t What We Thought They Were

[/caption]

The origin of cosmic rays has been one of the most enduring mysteries in physics, and it looks like it’s going to stay that way for a while longer. One of the leading candidates for where cosmic rays come from is gamma ray bursts, and physicists were hoping a huge Antarctic detector called the IceCube Neutrino Observatory would confirm that theory. But observations of over 300 GRB’s turned up no evidence of cosmic rays. In short, cosmic rays aren’t what we thought they were.

But, just like Thomas Edison who said that “every wrong attempt discarded is another step forward,” physicists view this latest finding as progress.

“Although we have not discovered where cosmic rays come from, we have taken a major step towards ruling out one of the leading predictions,” said IceCube principal investigator and University of Wisconsin–Madison physics professor Francis Halzen.

Cosmic rays are electrically charged particles, such as protons, that strike Earth from all directions, with energies up to one hundred million times higher than those created in man-made accelerators. The intense conditions needed to generate such energetic particles have focused physicists’ interest on two potential sources: the massive black holes at the centers of active galaxies and gamma ray bursts (GRBs), flashes of gamma rays associated with extremely energetic explosions that have been observed in distant galaxies.

IceCube is using neutrinos, which are believed to accompany cosmic ray production, to explore these two theories. In a paper published in the April 19 issue of the journal Nature, IceCube scientists describe a search for neutrinos emitted from 300 gamma ray bursts observed, most recently in coincidence with the SWIFT and Fermi satellites, between May 2008 and April 2010. Surprisingly, they found none – a result that contradicts 15 years of predictions and challenges one of the two leading theories for the origin of the highest energy cosmic rays.

The detector searches for high-energy (teraelectronvolt; 1012-electronvolt) neutrinos, and in their paper the team said they found an upper limit on the flux of energetic neutrinos associated with GRBs that is at least a factor of 3.7 below the predictions. This implies that either GRBs are not the only sources of cosmic rays with energies greater than 1018More info on IceCube.

Source: IceCube/University of Wisconsin

Journal Club – Neutrino Vision

[/caption]

According to Wikipedia, a journal club is a group of individuals who meet regularly to critically evaluate recent articles in the scientific literature. And of course, the first rule of Journal Club is… don’t talk about Journal Club.

So, without further ado – today’s journal article is about the latest findings in neutrino astronomy.

Today’s article:

Gaisser Astrophysical neutrino results..

This paper presents some recent observations from the IceCube neutrino telescope at the South Pole – which acually observes neutrinos from the northern sky – using the Earth to filter out some of the background noise. Cool huh?

Firstly, a quick recap of neutrino physics. Neutrinos are sub-atomic particles of the lepton variety and are essentially neutrally charged versions of the other leptons – electrons, muons and taus – which all have a negative charge. So, we say that neutrinos come in three flavours – electron neutrinos, muon neutrinos and tau neutrinos.

Neutrinos were initially proposed by Pauli (a proposal later refined by Fermi) to explain how energy could be transported away from a system undergoing beta decay. When solar fusion began to be understood in the 1930s – the role of neutrinos was problematic since only a third or more of the neutrinos that were predicted to be produced by fusion were being detected – an issue which became known as the solar neutrino problem in the 1960’s.

The solar neutrino problem was only resolved in the late 1990s when the three neutrino flavours idea gained wide acceptance and each were finally detected in 2001 – confirming that solar neutrinos in transit actually oscillate between the three flavours (electron, muon and tau) – which means that if your detector is set up to detect only one flavour you will detect only about one third of all the neutrinos coming from the Sun.

Ten years later, the Ice Cube the neutrino observatory is using our improved understanding of neutrinos to try and detect high energy neutrinos of extragalactic origin. The first challenge is to distinguish atmospheric neutrinos (produced in abundance as cosmic rays strike the atmosphere) from astrophysical neutrinos.

Using what we have learnt from solving the solar neutrino problem, we can be confident that any neutrinos from distant sources have had time to oscillate – and hence should arrive at Earth in approximately equal ratios. Atmospheric neutrinos produced from close sources (also known as ‘prompt’ neutrinos) don’t have time to oscillate before being detected.

When looking for point sources of high energy astrophysical neutrinos, IceCube is most sensitive to muon neutrinos – which are detected when the neutrino weakly interacts with an ice molecule – emitting a muon. A high energy muon will then generate Cherenkov radiation – which is what IceCube actually detects. Unfortunately muon neutrinos are also the most common source of cosmic ray induced atmospheric neutrinos, but we are steadily getting better at determining what energy levels represent astrophysical rather than atmospheric neutrinos.

So, it’s still early days with this technology – with much of the effort going in to learning how to observe, rather than just observing. But maybe one day we will be observing the cosmic neutrino background – and hence the first second of the Big Bang. One day…

So… comments? Are neutrinos the fundamentally weirdest fundamental particle out there? Could IceCube be used to test the faster-than-light neutrino hypothesis? Want to suggest an article for the next edition of Journal Club?

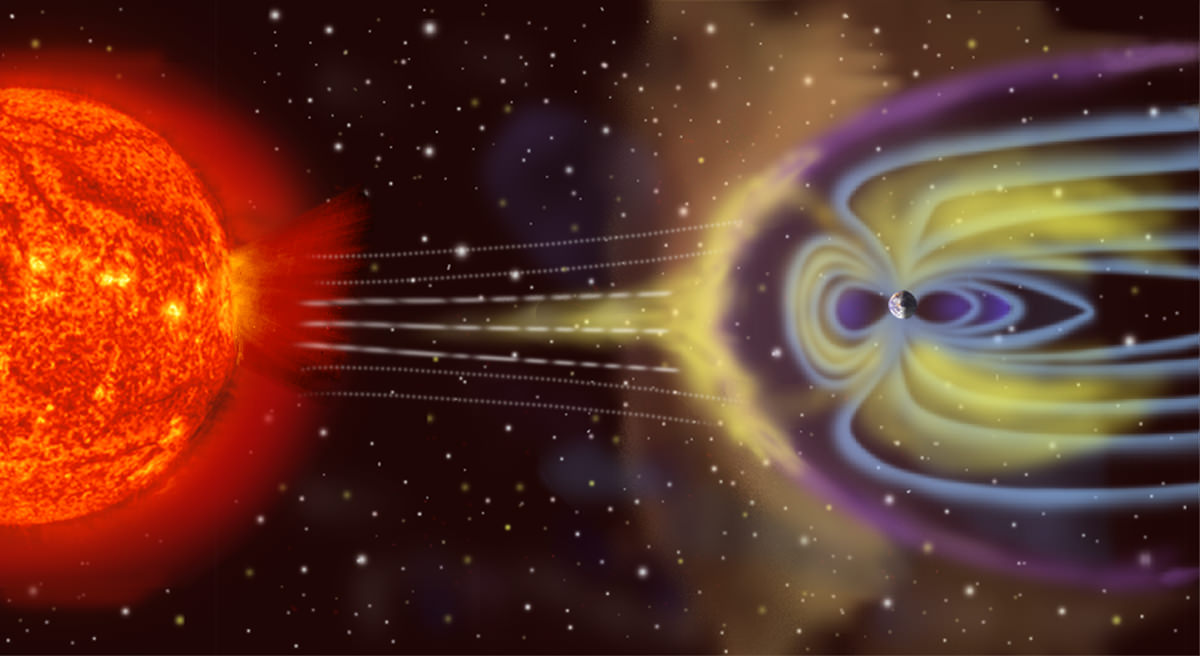

Can Solar Flares Hurt Astronauts?

[/caption]

Solar flares, coronal mass ejections, high-energy photons, cosmic rays… space is full of various forms of radiation that a human wouldn’t want to be exposed to for very long. Energized particles traveling into and through the body can cause a host of nasty health problems, from low blood count to radiation sickness to cataracts and cancer… and potentially even death. Luckily Earth’s magnetic field and atmosphere protects us on the surface from much of this radiation, but what about the astronauts aboard the Space Station? How could events such as today’s powerful near-X-class solar flare and last week’s CME affect them, orbiting 240 miles above Earth’s surface?

Surprisingly, they are safer than you might think.

The M8.7-class flare that erupted from the Sun early on Jan. 23 sent a huge wave of high-energy protons Earthward, creating the largest solar storm seen since 2005. The cloud of energetic particles raced outwards through the Sun’s atmosphere at speeds well over a million miles per hour, blowing past our planet later the same day. (More slower-moving charged particles will impact the magnetosphere in the coming days.) We are safe on Earth but astronauts exposed to such radiation could have faced serious health risks. Fortunately, most solar protons cannot pass through the hull of the Space Station and so as long as the astronauts stay inside, they are safe.

Of course, this is not the case with more dangerous cosmic rays.

According to the NASA Science site:

Cosmic rays are super-charged subatomic particles coming mainly from outside our solar system. Sources include exploding stars, black holes and other characters that dwarf the sun in violence. Unlike solar protons, which are relatively easy to stop with materials such as aluminum or plastic, cosmic rays cannot be completely stopped by any known shielding technology.

Even inside their ships, astronauts are exposed to a slow drizzle of cosmic rays coming right through the hull. The particles penetrate flesh, damaging tissue at the microscopic level. One possible side-effect is broken DNA, which can, over the course of time, cause cancer, cataracts and other maladies.

In a nutshell, cosmic rays are bad. Especially in large, long-term doses.

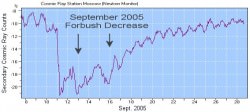

Now the astronauts aboard the ISS are still well within Earth’s protective magnetic field and so are shielded from much of the cosmic radiation that passes through our solar system daily. And, strangely enough, when solar flares occur – such as today’s – the amount of cosmic radiation the ISS encounters actually decreases.

Why?

The solar particles push them away.

In an effect known as the “Forbush decrease”, magnetically-charged particles ejected from the Sun during flares and CMEs reduce the amount of cosmic radiation the ISS experiences, basically because they “sweep away” other charged particles of more cosmic origin.

Because cosmic rays can easily penetrate the Station’s hull, and solar protons are much less able to, the irony is that astronauts are actually a degree safer during solar storms than they would be otherwise.

And it’s not just in low-Earth orbit, either: Wherever CMEs go, cosmic rays are deflected. Forbush decreases have been observed on Earth and in Earth orbit onboard Mir and the ISS. The Pioneer 10 and 11 and Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft have experienced them, too, beyond the orbit of Neptune. (via NASA Science.)

Due to this unexpected side effect of solar activity it’s quite possible that future manned missions to the Moon, Mars, an asteroid, etc. would be scheduled during a period of solar maximum, like the one we are in the middle of right now. The added protection from cosmic rays would be a big benefit for long-duration missions since we really don’t know all the effects that cosmic radiation may have on the human body. We simply haven’t been traveling in space long enough. But the less exposure to radiation, the better it is for astronauts.

Maybe solar storms aren’t so bad after all.

Read more about solar radiation and the Forbush decrease on NASA Science here.

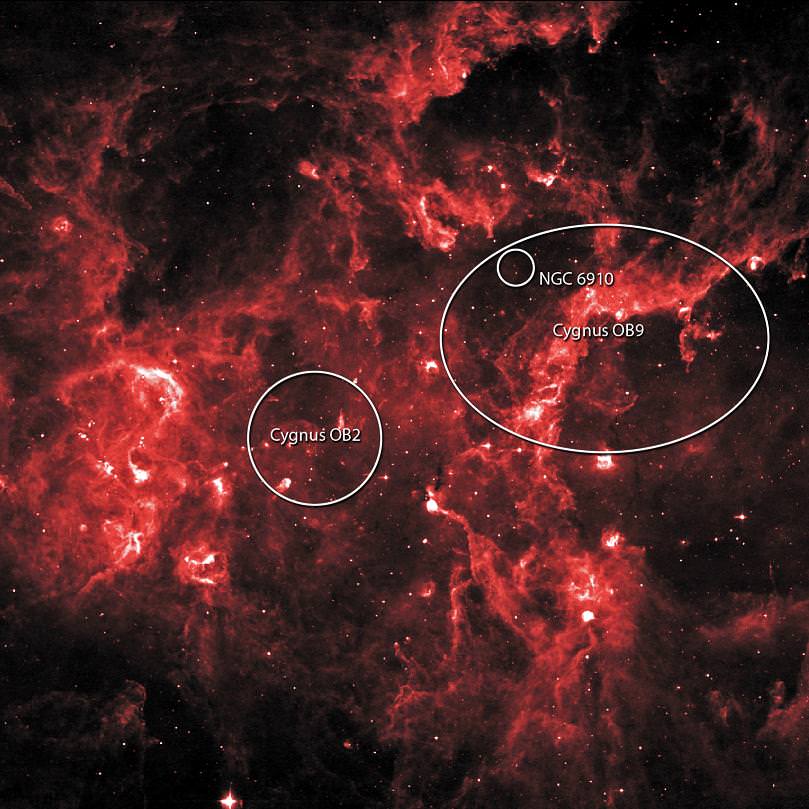

Cygnus X – A Cosmic-ray Cocoon

[/caption]

Situated about 4,500 light-years away in the constellation of Cygnus is a veritable star factory called Cygnus X… one estimated to have enough “raw materials” to create as many as two million suns. Caught in the womb are stellar clusters and OB associations. Of particular interest is one labeled Cygnus OB2 which is home to 65 of the hottest, largest and meanest O-type stars known – and close to 500 B members. The O boys blast out holes in the dust clouds in intense outflows, disrupting cosmic rays. Now, a study using data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is showing us this disturbance can be traced back to its source.

Discovered some 60 years ago in radio frequencies, the Cygnus X region has long been of interest, but dust-veiled at optical wavelengths. By employing NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, scientists are now able to peer behind the obscuration and take a look at the heart through gamma ray observations. In regions of star formation like Cygnus X, subatomic particles are produced and these cosmic rays shoot across our galaxy at light speed. When they collide with interstellar gas, they scatter – making it impossible to trace them to their point of origin. However, this same collision produces a gamma ray source… one that can be detected and pinpointed.

“The galaxy’s best candidate sites for cosmic-ray acceleration are the rapidly expanding shells of ionized gas and magnetic field associated with supernova explosions.” says the FERMI team. “For stars, mass is destiny, and the most massive ones — known as types O and B — live fast and die young.”

Because these star types aren’t very common, regions like Cygnus X become important star laboratories. Its intense outflows and huge amount of mass fills the prescription for study. Within its hollowed-out walls, stars reside in layers of thin, hot gas enveloped in ribbons of cool, dense gas. It is this specific area in which Fermi’s LAT instrumentation excels – detecting an incredible amount of gamma rays.

“We are seeing young cosmic rays, with energies comparable to those produced by the most powerful particle accelerators on Earth. They have just started their galactic voyage, zig-zagging away from their accelerator and producing gamma rays when striking gas or starlight in the cavities,” said co-author Luigi Tibaldo, a physicist at Padova University and the Italian National Institute of Nuclear Physics.

Clocked at up to 100 billion electron volts by the LAT, these highly accelerated particles are revealing the extreme origin of gamma-ray emission. For example, visible light is only two to three electron volts! But why is Cygnus X so special? It entangles its sources in complex magnetic fields and keeps the majority of them from escaping. All thanks to those high mass stars…

“These shockwaves stir the gas and twist and tangle the magnetic field in a cosmic-scale jacuzzi so the young cosmic rays, freshly ejected from their accelerators, remain trapped in this turmoil until they can leak into quieter interstellar regions, where they can stream more freely,” said co-author Isabelle Grenier, an astrophysicist at Paris Diderot University and the Atomic Energy Commission in Saclay, France.

However, there’s more to the story. The Gamma Cygni supernova remnant is also nearby and may impact the findings as well. At this point, the Fermi team considers it may have created the initial “cocoon” which holds the cosmic rays in place, but they also concede the accelerated particles may have originated through multiple interactions with stellar winds.

“Whether the particles further gain or lose energy inside this cocoon needs to be investigated, but its existence shows that cosmic-ray history is much more eventful than a random walk away from their sources,” Tibaldo added.

Original Story Source: NASA Fermi News.

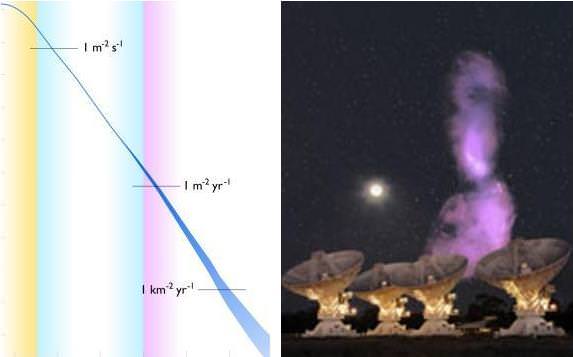

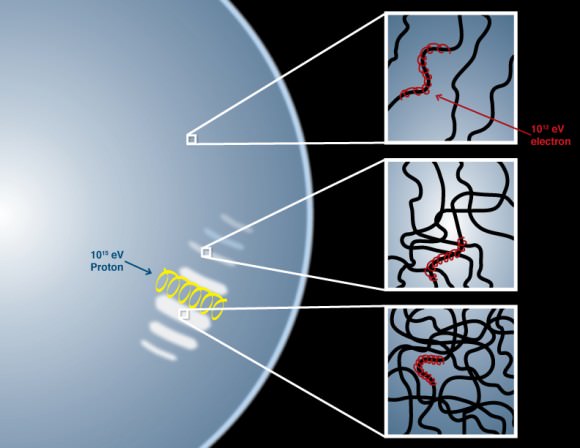

Astronomy Without A Telescope – Oh-My-God Particles

[/caption]

Cosmic rays are really sub-atomic particles, being mainly protons (hydrogen nuclei) and occasionally helium or heavier atomic nuclei and very occasionally electrons. Cosmic ray particles are very energetic as a result of them having a substantial velocity and hence a substantial momentum.

The Oh-My-God particle detected over Utah in 1991 was probably a proton traveling at 0.999 (and add another 20 x 9s after that) of the speed of light and it allegedly carried the same kinetic energy as a baseball traveling at 90 kilometers an hour.

Its kinetic energy was estimated at 3 x 1020 electron volts (eV) and it would have had the collision energy of 7.5 x 1014 eV when it hit an atmospheric particle – since it can’t give up all its kinetic energy in the collision. Fast moving debris carries some of it away and there’s some heat loss too. In any case, this is still about 50 times the collision energy we expect the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) will be able to generate at full power. So, this gives you a sound basis to scoff at doomsayers who are still convinced that the LHC will destroy the Earth.

Now, most cosmic ray particles are low energy, up to 1010 eV – and arise locally from solar flares. Another more energetic class, up to 1015 eV, are thought originate from elsewhere in the galaxy. It’s difficult to determine their exact source as the magnetic fields of the galaxy and the solar system alter their trajectories so that they end up having a uniform distribution in the sky – as though they come from everywhere.

But in reality, these galactic cosmic rays probably come from supernovae – quite possibly in a delayed release process as particles bounce back and forth in the persisting magnetic field of a supernova remnant, before being catapulted out into the wider galaxy.

And then there are extragalactic cosmic rays, which are of the Oh-My-God variety, with energy levels exceeding 1015 eV, even rarely exceeding 1020 eV – which are more formally titled ultra-high-energy cosmic rays. These particles travel very close to the speed of light and must have had a heck of kick to attain such speeds.

However, a perhaps over-exaggerated aura of mystery has traditionally surrounded the origin of extragalactic cosmic rays – as exemplified in the Oh-My-God title.

In reality, there are limits to just how far away an ultra-high-energy particle can originate from – since, if they don’t collide with anything else, they will eventually come up against the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin (GZK) limit. This represents the likelihood of a fast moving particle eventually colliding with a cosmic microwave background photon, losing momentum energy and velocity in the process. It works out that extragalactic cosmic rays retaining energies of over 1019 eV cannot have originated from a source further than 163 million light years from Earth – a distance known as the GZK horizon.

Recent observations by the Pierre Auger Observatory have found a strong correlation between extragalactic cosmic rays patterns and the distribution of nearby galaxies with active galactic nuclei. Biermann and Souza have now come up with an evidence-based model for the origin of galactic and extragalactic cosmic rays – which has a number of testable predictions.

They propose that extragalactic cosmic rays are spun up in supermassive black hole accretion disks, which are the basis of active galactic nuclei. Furthermore, they estimate that nearly all extragalactic cosmic rays that reach Earth come from Centaurus A. So, no huge mystery – indeed a rich area for further research. Particles from an active supermassive black hole accretion disk in another galaxy are being delivered to our doorstep.

Further reading: Biermann and Souza On a common origin of galactic and extragalactic cosmic rays.

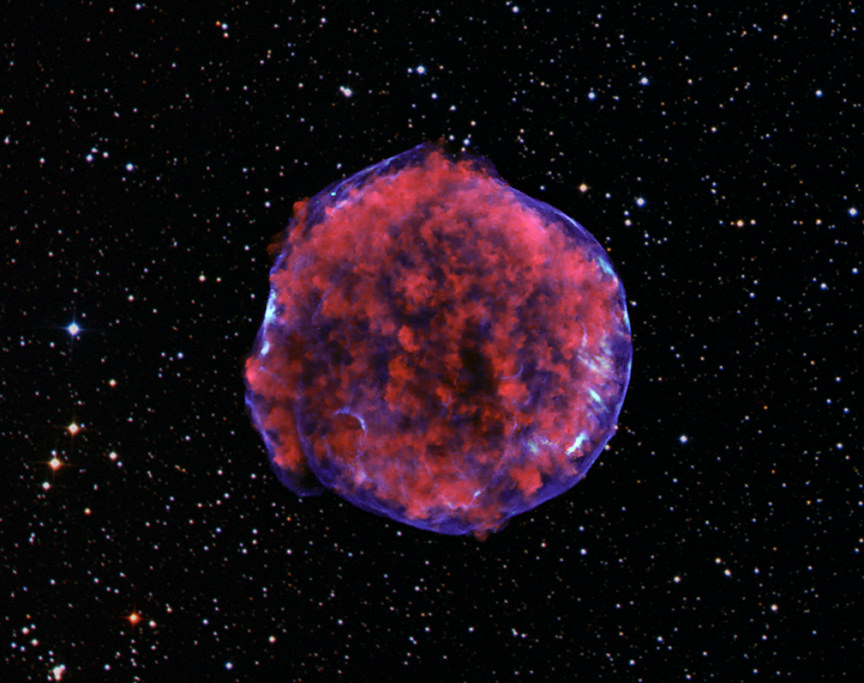

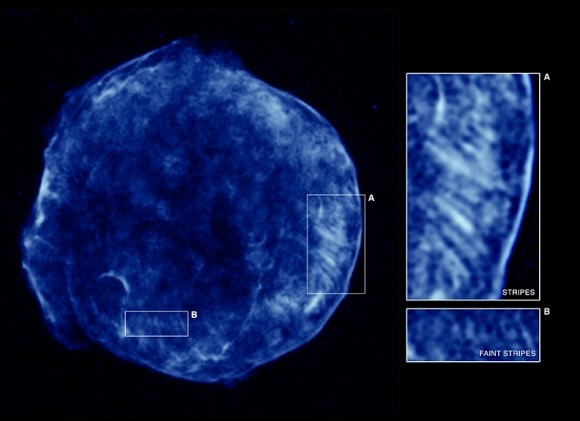

New Look Inside Tycho Supernova Remnant Hints at Cosmic Ray Origins

[/caption]

The Chandra X-Ray Observatory has taken a brand new, deep look inside the Tycho Supernova Remnant and found a pattern of X-ray “stripes.” The three-dimensional-like nature of this incredible image notwithstanding, nothing like these stripe-like features has ever been seen before inside the leftovers of an exploding star, but astronomers believe they could explain how some cosmic rays are created. Additionally, the stripes provide support for a theory about how magnetic fields can be dramatically amplified in supernova blast waves.

Cosmic rays are made up of electrons, positrons and atomic nuclei and they constantly bombard the Earth. In their near light-speed journey across the galaxy, the particles are deflected by magnetic fields, which scramble their paths and mask their origins. Supernova remnants have long been thought to be the source of cosmic rays, up to the “knee” of the cosmic ray spectrum at 10^15 eV, but so far, no specific sources have been located.

In 2010, the Fermi gamma ray telescope found evidence – also from supernova remnants – where radiation is emitted that is a billion times more energetic than visible light.

But the stripes seen by Chandra, shown above in high-energy X-rays (blue), are thought to be regions where the turbulence is greater and the magnetic fields more tangled than surrounding areas. Electrons become trapped in these regions and emit X-rays as they spiral around the magnetic field lines. Regions with enhanced turbulence and magnetic fields were expected in supernova remnants, but the motion of the most energetic particles — mostly protons — was predicted to leave a messy network of holes and dense walls corresponding to weak and strong regions of magnetic fields, respectively.

Therefore, the detection of stripes was a surprise.

The size of the holes was expected to correspond to the radius of the spiraling motion of the highest energy protons in the supernova remnant. These energies equal the highest energies of cosmic rays thought to be produced in our Galaxy. The spacing between the stripes corresponds to this size, providing evidence for the existence of these extremely energetic protons.

“We interpret the stripes as evidence for acceleration of particles to near the knee of the CR spectrum in regions of enhanced magnetic turbulence, while the observed highly ordered pattern of these features provides a new challenge to models of diffusive shock acceleration,” writes Kristoffer A. Eriksen and his team in their paper, “Evidence For Particle Acceleration to the Knee of the Cosmic Ray Spectrum in Tycho’s Supernova Remnant.”

Source: Chandra

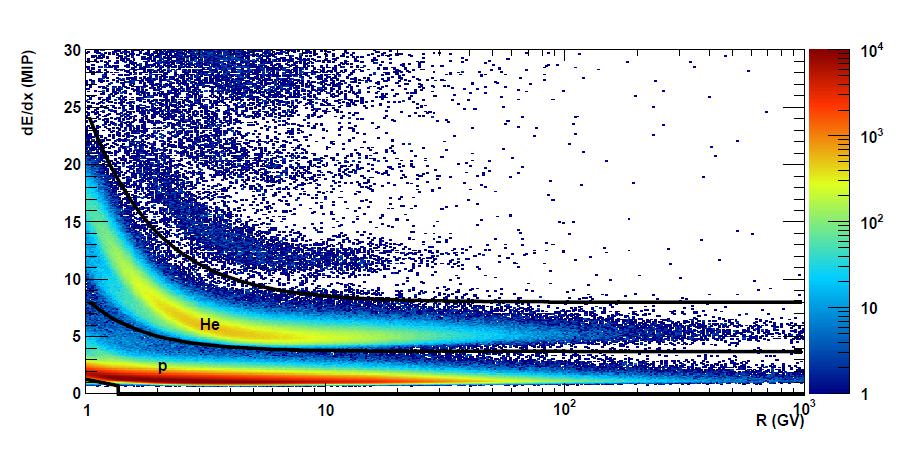

PAMELA Uncovers Cosmic Ray Surprise

[/caption]

High energy particles called cosmic rays are constantly bombarding Earth from all directions, and have been thought to come from the blast waves of supernova remnants. But new observations from the PAMELA cosmic ray detector show an unexpected difference in the speeds of protons and helium nuclei, the most abundant components of cosmic rays. The difference is extremely small, but if they were accelerated from the same event, the speeds should be the same.

PAMELA, the Payload for Anti-Matter Exploration and light-Nuclei Astrophysics, is on board the Earth-orbiting Russian Resurs-DK1 satellite. It uses a permanent magnet spectrometer along with a variety of specialized detectors to measure the abundance and energy spectra of cosmic rays electrons, positrons, antiprotons and light nuclei over a very large range of energy from 50 MeV to hundreds of GeV.

Just as astronomers use light to view the Universe, scientists use galactic cosmic rays to learn more about the composition and structure of our galaxy, as well as to find out how things like how nuclei can accelerate to nearly the speed of light.

Oscar Adriani and his colleagues using the PAMELA instrument say their new findings are a challenge to our current understanding of how cosmic rays are accelerated and propagated. “We find that the spectral shapes of these two species are different and cannot be well described by a single power law,” the team writes in their paper. “These data challenge the current paradigm of cosmic-ray acceleration in supernova remnants followed by diffusive propagation in the Galaxy.”

Instead, the team concludes, the acceleration and propagation of cosmic rays may be controlled by now unknown and more complex processes.

Supernova remnants are expanding clouds of gas and magnetic fields and can last for thousands of years. Within this cloud, particles are accelerated by bouncing back and forth in the magnetic field of the remnant, and some of the particles gain energy, and eventually they build up enough speed that the remnant can no longer contain them, and they escape into the Galaxy as cosmic rays.

One key question that scientists hope to answer with PAMELA data is whether the cosmic rays are continuously accelerated over their entire lifetime, whether the acceleration occurs just once, or if there is any deceleration.

Scientists say that determining the fluxes in the proton and helium nuclei will give information about the early Universe as well as the origin and evolution of material in our galaxy.

Adriani and his team hope to uncover more information with PAMELA to help better understand the origins of cosmic rays. They say possible contributions could be from additional galactic sources, such as pulsars or dark matter.

Abstract: PAMELA Measurements of Cosmic-Ray Proton and Helium Spectra

Source: Science

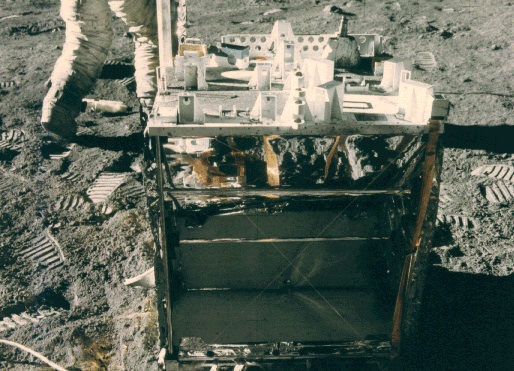

Astronomy Without A Telescope – A Universe Free Of Charge?

[/caption]

If there were equal amounts of matter and anti-matter in the universe, it would be easy to deduce that the universe has a net charge of zero, since a defining ‘opposite’ of matter and anti-matter is charge. So if a particle has charge, its anti-particle will have an equal but opposite charge. For example, protons have a positive charge – while anti-protons have a negative charge.

But it’s not apparent that there is a lot of anti-matter around as neither the cosmic microwave background, nor the more contemporary universe contain evidence of annihilation borders – where contact between regions of large scale matter and large scale anti-matter should produce bright outbursts of gamma rays.

So, since we do apparently live in a matter-dominated universe – the question of whether the universe has a net charge of zero is an open question.

It’s reasonable to assume that dark matter has either a net zero charge – or just no charge at all – simply because it is dark. Charged particles and larger objects like stars with dynamic mixtures of positive and negative charges, produce electromagnetic fields and electromagnetic radiation.

So, perhaps we can constrain the question of whether the universe has a net charge of zero to just asking whether the total sum of all non-dark matter has. We know that most cold, static matter – that is in an atomic, rather than a plasma, form – should have a net charge of zero, since atoms have equal numbers of positively charged protons and negatively charged electrons.

Stars composed of hot plasma might also be assumed to have a net charge of zero, since they are the product of accreted cold, atomic material which has been compressed and heated to create a plasma of dissociated nuclei (+ve) and electrons (-ve).

The principle of charge conservation (which is accredited to Benjamin Franklin) has it that the amount of charge in a system is always conserved, so that the amount flowing in will equal the amount flowing out.

An experiment which has been suggested to enable measurement of the net charge of the universe, involves looking at the solar system as a charge-conserving system, where the amount flowing in is carried by charged particles in cosmic rays – while the amount flowing out is carried by charged particles in the Sun’s solar wind.

If we then look at a cool, solid object like the Moon, which has no magnetic field or atmosphere to deflect charged particles, it should be possible to estimate the net contribution of charge delivered by cosmic rays and by solar wind. And when the Moon is shadowed by the tail of the Earth’s magnetosphere, it should be possible to detect the flux attributable to just cosmic rays – which should represent the charge status of the wider universe.

Drawing on data collected from sources including Apollo surface experiments, the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the WIND spacecraft and the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer flown on a space shuttle (STS 91), the surprising finding is a net overbalance of positive charges arriving from deep space, implying that there is an overall charge imbalance in the cosmos.

Either that or a negative charge flux occurs at energy levels lower than the threshold of measurement that was achievable in this study. So perhaps this study is a bit inconclusive, but the question of whether the universe has a net charge of zero still remains an open question.

Further reading: Simon, M.J. and Ulbricht, J. (2010) Generating an electrical potential on the Moon by cosmic rays and solar wind?