Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the Andromeda Galaxy, also known as Messier 31. Enjoy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

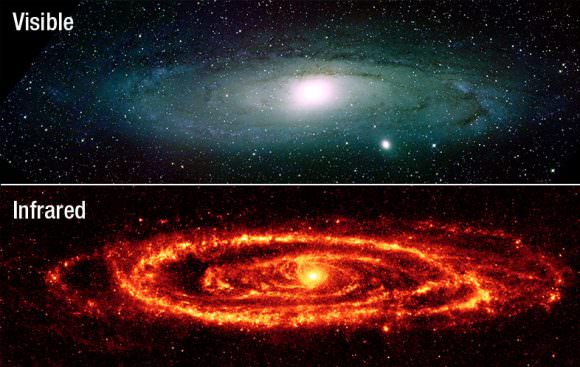

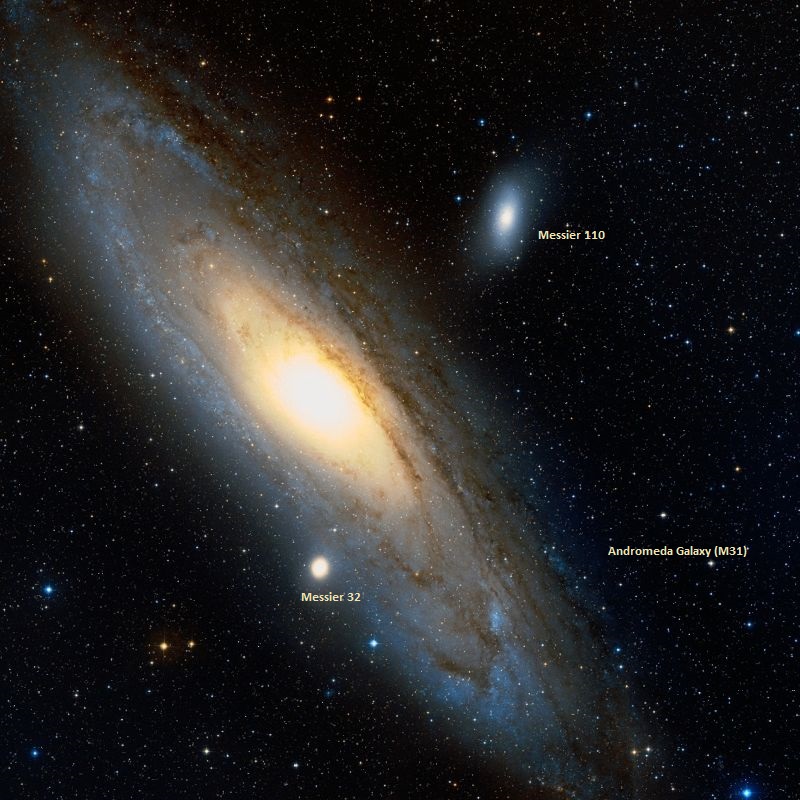

One of these objects is the famed Andromeda Galaxy, the closest spiral galaxy to the Milky Way which is named for the area of the sky it appears in (in the vicinity of the Andromeda constellation). It is the largest galaxy in the Local Group, and has the distinction of being one of the few objects that is actually getting closer to the Milky Way (and is expected to merge with us in a few billion years!).

Description:

Approaching us at roughly 300 kilometers per second, our massive galactic neighbor has been the object of studies of spiral structure, globular and open clusters, interstellar matter, planetary nebulae, supernova remnants, galactic nucleus, companion galaxies, and more for as long as we’ve been peering its way with a telescope. It’s part of our Local Group of galaxies and its two easily visible companions are only part of the eleven others that swarm around it.

One day, this galaxy will collide with our own, much as it is now consuming its neighbor – M32. However, this won’t come to pass for several billions years, so don’t go worrying about the immense gravitational disturbances just yet! And not surprisingly, a giant galaxy like Andromeda doesn’t get to be so big by keeping to itself. How many times now has the Great Andromeda Galaxy consumed another? More than once!

In 1993, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed that M31 has a double nucleus – a ‘leftover’ from another meal! As NASA and the ESA stated about the discovery at the time:

“Each of the two light-peaks contains a few million densely packed stars. The brighter object is the “classic” nucleus as studied from the ground. However, HST reveals that the true center of the galaxy is really the dimmer component. One possible explanation is that the brighter cluster is the leftover remnant of a galaxy cannibalized by M31. Another idea is that the true center of the galaxy has been divided in two by deep dust absorption across the middle, creating the illusion of two peaks. This green-light image was taken with HST’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera (WF/PC), in high resolution mode, on July 6, 1991. The two peaks are separated by 5 light-years. The Hubble image is 40 light-years across.”

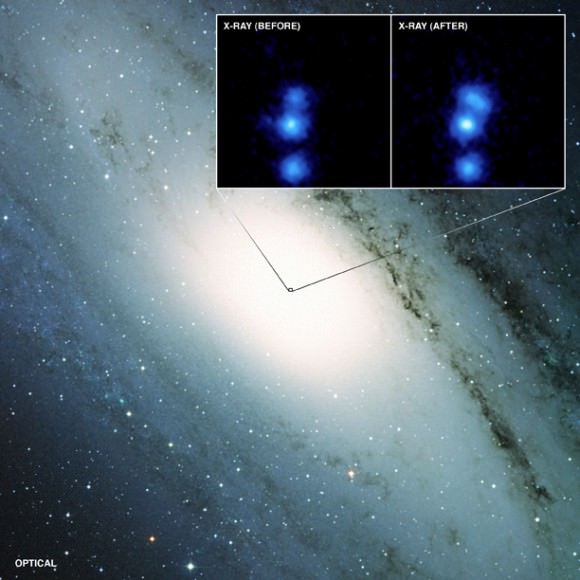

Perhaps one of the most fascinating discovery recent years in Messier 31 was made by the orbiting Chandra X-Ray Observatory. The X-ray image below, made with the Chandra X-Ray Astronomy Center’s Advanced CCD Imaging Spectrometer (ACIS), shows the central portion of the Andromeda Galaxy. The Chandra X-ray Observatory is part of NASA’s fleet of “Great Observatories” along with the Hubble Space Telescope.

The blue dot in the center of the image is a “cool” million degree X-ray source where Andromeda’s massive central object, with the mass of 30 million suns, is located, which many astronomers consider to be a supermassive black hole. Most of these are probably due to X-ray binary systems, in which a neutron star (or perhaps a stellar black hole) is in a close orbit around a normal star.”

Over the years our studies have advanced even more with the discovery of an eclipsing binary star in Messier 31. As Ignasi Ribas (et al) put it in a 2005:

“We present the first detailed spectroscopic and photometric analysis of an eclipsing binary in the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). This is a 19.3 mag semidetached system with late O and early B spectral type components. From the light and radial velocity curves we have carried out an accurate determination of the masses and radii of the components. Their effective temperatures have been estimated by modeling the absorption-line spectra. The analysis yields an essentially complete picture of the properties of the system, and hence an accurate distance determination to M31.”

In 2005, we discovered more. At that time, Scott Chapman of Caltech, Rodrigo Ibata of the Observatoire de Strasbourg, and their colleagues conducted detailed studies on the motions and metals of nearly 10,000 stars in Andromeda, which that the galaxy’s stellar halo is “metal-poor.” Essentially, this indicated that the stars lying in the outer bounds of the galaxy are lacking in elements heavier than hydrogen.

According to Chapman, this was surprising since one of the key differences thought to exist between Andromeda and the Milky Way was that the former’s stellar halo was metal-rich and the latter’s was metal-poor. If both galaxies are metal-poor, then they must have had very similar evolutions. As Chapman explained:

“Probably, both galaxies got started within a half billion years of the Big Bang, and over the next three to four billion years, both were building up in the same way by protogalactic fragments containing smaller groups of stars falling into the two dark-matter haloes.”

While no one yet knows what dark matter is made of, its existence is well established because of the mass that must exist in galaxies for their stars to orbit the galactic centers. In fact, current theories of galactic evolution assume that dark-matter wells acted as a sort of “seed” for today’s galaxies, with the dark matter pulling in smaller groups of stars as they passed nearby.

What’s more, galaxies like Andromeda and the Milky Way have each probably gobbled up about 200 smaller galaxies and protogalactic fragments over the last 12 billion years. Chapman and his colleagues arrived at the conclusion about the metal-poor Andromeda halo by obtaining careful measurements of the speed at which individual stars are coming directly toward or moving directly away from Earth.

This measure is called the radial velocity, and can be determined very accurately with the spectrographs of major instruments such as the 10-meter Keck-II telescope, which was used in the study. Of the approximately 10,000 Andromeda stars for which the researchers have obtained radial velocities, about 1,000 turned out to be stars in the giant stellar halo that extends outward by more than 500,000 light-years.

These stars, because of their lack of metals, are thought to have formed quite early, at a time when the massive dark-matter halo had captured its first protogalactic fragments. The stars that dominate closer to the center of the galaxy, by contrast, are those that formed and merged later, and contain heavier elements due to stellar evolution processes.In addition to being metal-poor, the stars of the halo follow random orbits and are not in rotation.

By contrast, the stars of Andromeda’s visible disk are rotating at speeds upwards of 200 kilometers per second.According to Ibata, the study could lead to new insights on the nature of dark matter. “This is the first time we’ve been able to obtain a panoramic view of the motions of stars in the halo of a galaxy,” says Ibata. “These stars allow us to weigh the dark matter, and determine how it decreases with distance.”

History of Observation:

Andromeda was known as the “Little Cloud” to Persian astronomer Abd-al-Rahman Al-Sufi, who described and depicted it in 964 AD in his Book of Fixed Stars. This wonderful galaxy was also cataloged by Giovanni Batista Hodierna in 1654, Edmund Halley in 1716, by Bullialdus 1664, and again by Charles Messier in 1764.

Like most of the objects he added to the Messier Catalog, he mistook the galaxy initially for a nebulous object. As he wrote of the object in his notes:

“The sky has been very good in the night of August 3 to 4, 1764; and the constellation Andromeda was near the Meridian, I have examined with attention the beautiful nebula in the girdle of Andromeda, which was discovered in 1612 by Simon Marius, and which has been observed since with great care by different astronomers, and at last by M. le Gentil who has given a very ample and detailed description in the volume of the Memoirs of the Academy for 1759, page 453, with a drawing of its appearance. I will not report here what I have written in my Journal: I have employed different instruments for examining that nebula, and above all an excellent Gregorian telescope of 30 pouces focal length, the large mirror having 6 pouces in diameter, and magnifying 104 times these objects: the middle of that nebula appeared rather bright with this instrument, without any appearance of stars; the light went diminishing up to extinguishing; it resembles two cones or pyramids of light, opposed at their bases, of which the axis was in the direction form North-West to South-East; the two points of light or the two summits are about 40 minutes of arc apart; I say about, because of the difficulty to recognize these two extremities. The common base of the two pyramids is 15 minutes: these measures have been made with a Newtonian telescope of 4 feet and a half focal length, equipped with a micrometer of silk wires. With the same instrument I have compared the middle of the summits of the two cones of light with the star Gamma Andromedae of fourth magnitude which is very near to it, and little distant from its parallel. From these observations, I have concluded the right ascension of the middle of this nebula as 7d 26′ 32″, and its declination as 39d 9′ 32″ north. Since fifteen years during which I viewed and observed this nebula, I have not noticed any change in its appearances; having always perceived it in the same shape.”

A great many astronomers would observe the Andromeda Galaxy over the years, each colorfully describing it. However, as we know from history, it would be quite some time before its true nature as an external galaxy would be discovered. Here is where we must give the utmost respect to Sir William Herschel, who knew way ahead of everyone else, that there was something very, very different about Messier’s Object 31!

Although he never publicly published his observing notes on another astronomer’s discoveries, it’s a shame he did not for this is what he had to say:

“.. But when an object is of such a construction, or at such a distance from us, that the highest power of penetration, which hitherto has been applied to it, leaves it undetermined whether it belongs to the class of nebulae or of stars, it may be called ambiguous. As there is, however, a considerable difference in the ambiguity of such objects, I have arranged 71 of them into the following four collections. The first contains seven objects that may be supposed to consist of stars, but where the observations hitherto made, of either their appearance or form, leave it undecided into which class they should be placed. Connoiss. 31 [M31] is: A large nucleus with very extensive nebulous branches, but the nucleus is very gradually joined to them. The stars which are scattered over it appear to be behind it, and seem to lose part of their lustre in the passage of their light through the nebulosity; there are not more of them scattered over the immediate neighborhood. I examined it in the meridian with a mirror of 24 inches in diameter, and saw it in high perfection; but its nature remains mysterious. Its light, instead of appearing resolvable with this aperture, seemed to be more milky. The objects in this collection must at present remain ambiguous.”

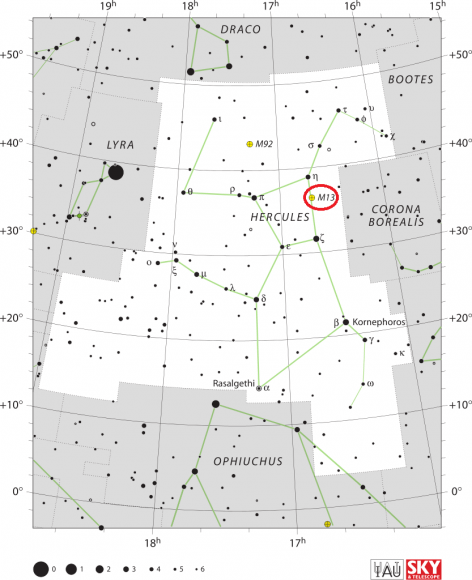

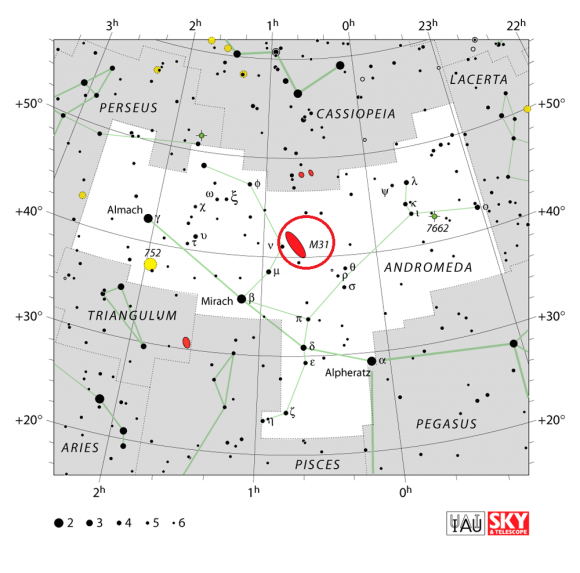

Locating Messier 31:

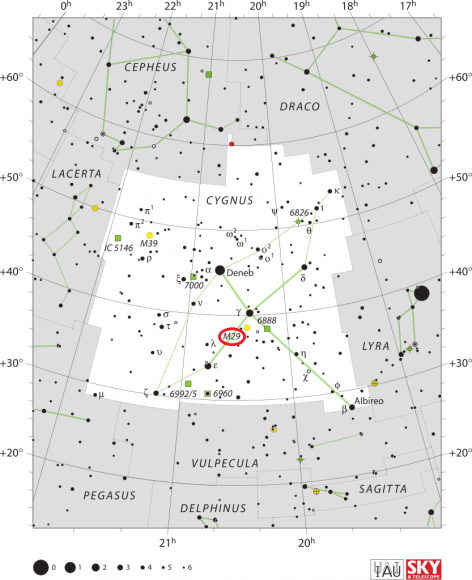

Even under moderately light polluted skies the Great Andromeda Galaxy, located in the Andromeda constellation, can be easily be found with the unaided eye – if you know where to look. Seasoned amateur astronomers can literally point to the sky and show you the location of M31, but perhaps you have never tried to find it. Believe it or not, this is an easy galaxy to spot even under the moonlight.

Simply identify the large diamond-shaped pattern of stars that is the Great Square of Pegasus. The northernmost star is Alpha, and it is here we will begin our hop. Stay with the northern chain of stars and look four finger widths away from Alpha for an easily seen star. The next along the chain is about three more finger widths away. Two more finger widths to the north and you will see a dimmer star that looks like it has something smudgy nearby.

Point your binoculars there, because that’s no cloud – it’s the Andromeda Galaxy! Now aim your binoculars or small telescope its way… Perhaps one of the most outstanding of all galaxies to the novice observer, M31 spans so much sky that it takes up several fields of view in a larger telescope, and even contains its own clusters and nebulae with New General Catalog designations.

If you have a slightly larger telescope, you may also be able to pick up M31’s two companions – M32 and M110. Even with no scope or binoculars, it’s pretty amazing that we can see something – anything! – that is over two million light-years away!

Enjoy this wonderful and mysterious galaxy at any and every opportunity! Even the most modest of optical aids will reveal it for what it is… Another island universe!

And here are ye’ ole’ quick facts. Enjoy!

Object Name: Messier 31

Alternative Designations: M31, NGC 224, Andromeda Galaxy

Object Type: Type Sb Galaxy

Constellation: Andromeda

Right Ascension: 00 : 42.7 (h:m)

Declination: +41 : 16 (deg:m)

Distance: 2900 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 3.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 178×63 (arc min)

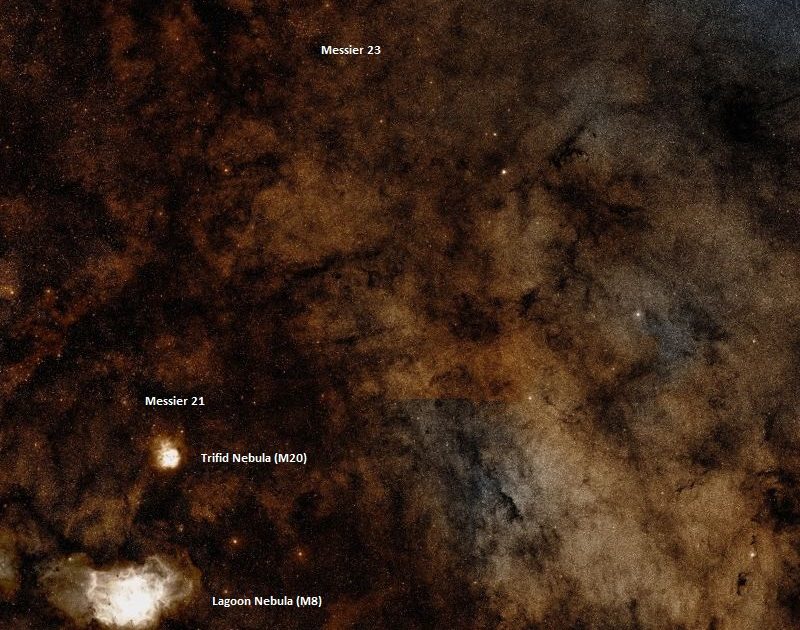

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources:

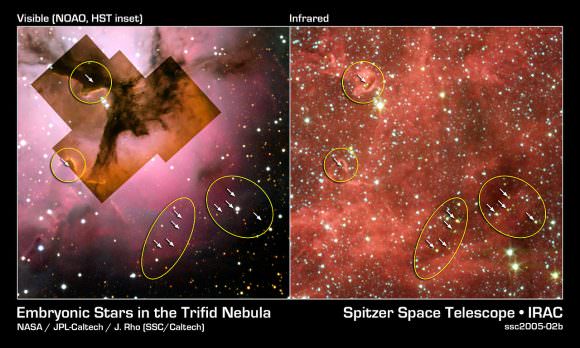

![The Trifid nebula (M20, NGC NGC 6514) in pseudocolor. Image taken with the Palomar 1.5-m telescope. The field of view is 16’ ´ 16’. Red shows [S II] ll 6717+6731. Green shows Ha l 6563. Blue shows [O III] l 5007. The WFPC2 field of view is indicated. Image: Jeff Hester (Arizona State University), Palomar telescope.](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/Trifid-Nebula-M20-e1469471610624-580x515.jpg)