[/caption]

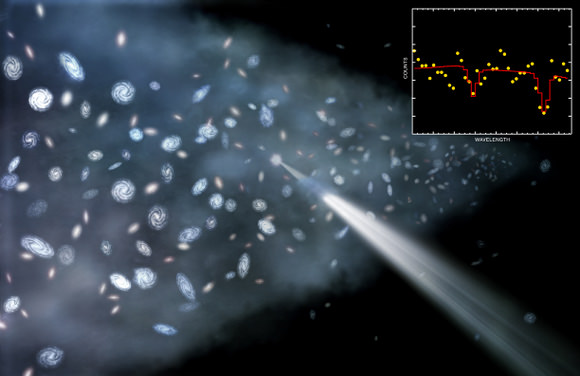

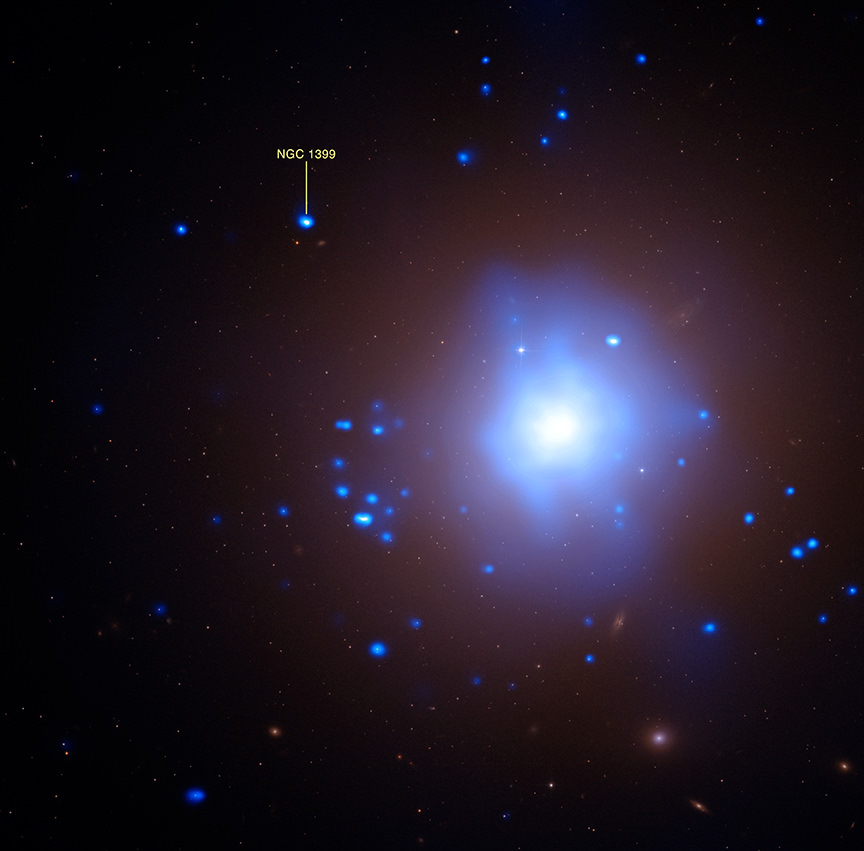

A galaxy cluster located about 10.2 billion light years from Earth has been discovered by combining data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory with optical and infrared telescopes. The cluster, JKCS041, is the most distant galaxy cluster yet observed, and we see it as when the Universe was only about a quarter of its present age. The cluster’s distance beats the previous record holder by about a billion light years.

Galaxy clusters are the largest gravitationally bound objects in the Universe. Finding such a large structure at this very early epoch can reveal important information about how the Universe evolved at this crucial stage.

JKCS041 is at the brink of when scientists think galaxy clusters can exist in the early Universe based on how long it should take for them to assemble. Therefore, studying its characteristics – such as composition, mass, and temperature – will reveal more about how the Universe took shape.

“This object is close to the distance limit expected for a galaxy cluster,” said Stefano Andreon of the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) in Milan, Italy. “We don’t think gravity can work fast enough to make galaxy clusters much earlier.”

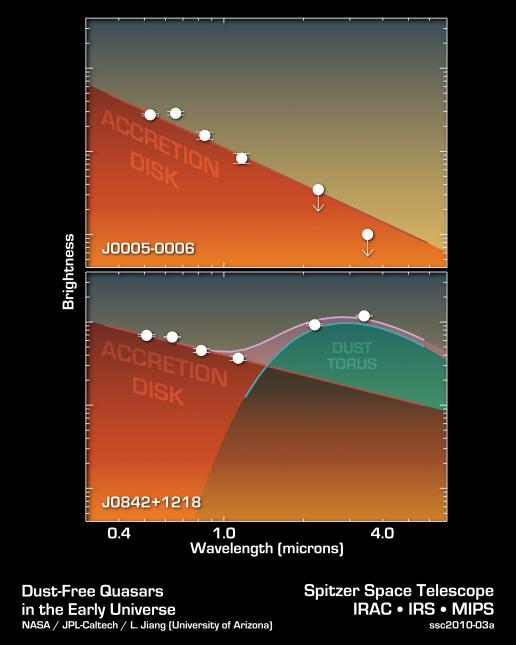

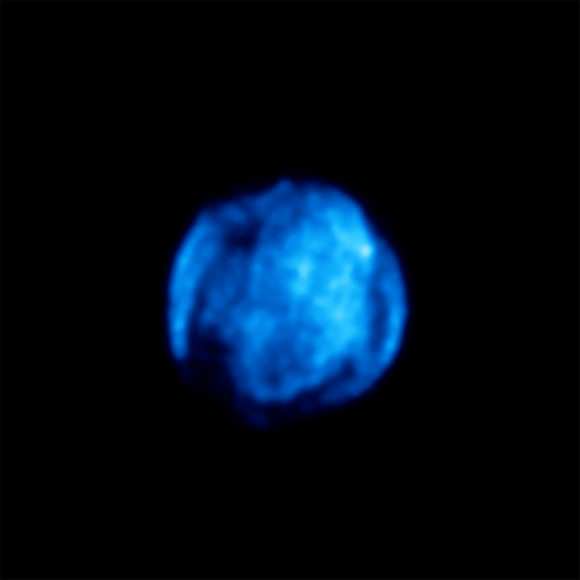

JKCS041 was originally detected in 2006 in a survey from the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope (UKIRT). The distance to the cluster was then determined from optical and infrared observations from UKIRT, the Canada-France-Hawaii telescope in Hawaii and NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. Infrared observations are important because the optical light from the galaxies at large distances is shifted into infrared wavelengths because of the expansion of the universe.

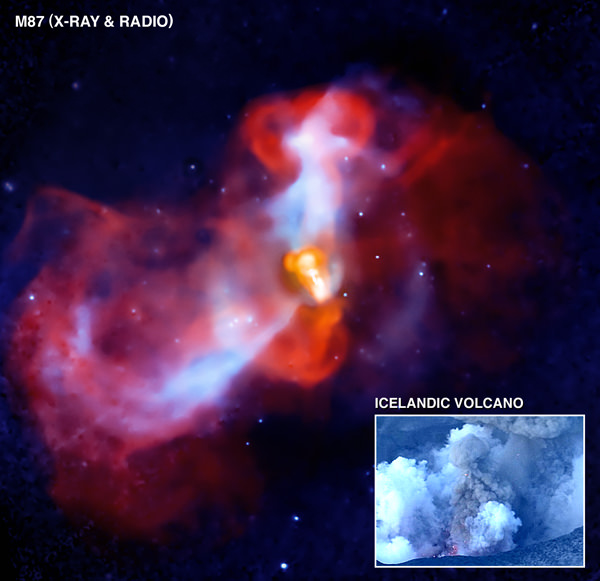

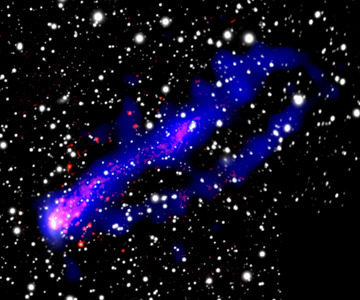

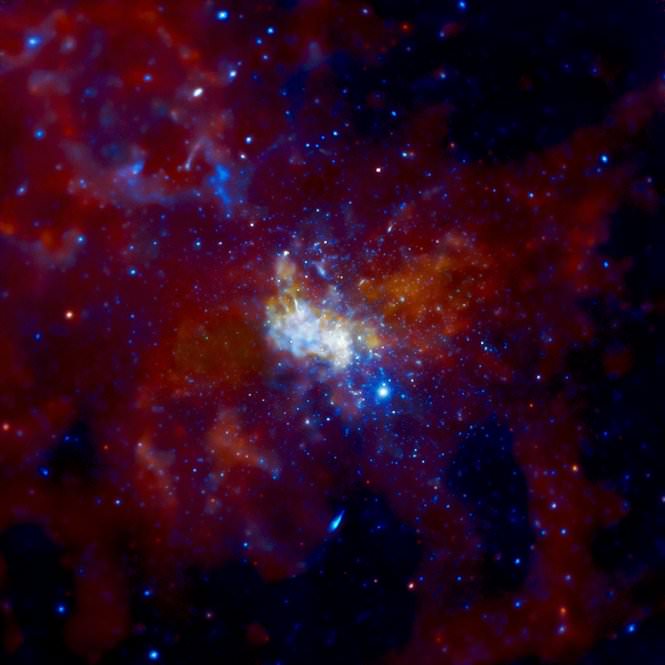

The Chandra data were the final – but crucial – piece of evidence as they showed that JKCS041 was, indeed, a genuine galaxy cluster. The extended X-ray emission seen by Chandra shows that hot gas has been detected between the galaxies, as expected for a true galaxy cluster rather than one that has been caught in the act of forming.

Also, without the X-ray observations, the possibility remained that this object could have been a blend of different groups of galaxies along the line of sight, or a filament, a long stream of galaxies and gas, viewed front on. The mass and temperature of the hot gas detected estimated from the Chandra observations rule out both of those alternatives.

The extent and shape of the X-ray emission, along with the lack of a central radio source argue against the possibility that the X-ray emission is caused by scattering of cosmic microwave background light by particles emitting radio waves.

It is not yet possible, with the detection of just one extremely distant galaxy cluster, to test cosmological models, but searches are underway to find other galaxy clusters at extreme distances.

“This discovery is exciting because it is like finding a Tyrannosaurus Rex fossil that is much older than any other known,” said co-author Ben Maughan, from the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom. “One fossil might just fit in with our understanding of dinosaurs, but if you found many more, you would have to start rethinking how dinosaurs evolved. The same is true for galaxy clusters and our understanding of cosmology.”

The previous record holder for a galaxy cluster was 9.2 billion light years away, XMMXCS J2215.9-1738, discovered by ESA’s XMM-Newton in 2006. This broke the previous distance record by only about 0.1 billion light years, while JKCS041 surpasses XMMXCS J2215.9 by about ten times that.

“What’s exciting about this discovery is the astrophysics that can be done with detailed follow-up studies,” said Andreon.

Among the questions scientists hope to address by further studying JKCS041 are: What is the build-up of elements (such as iron) like in such a young object? Are there signs that the cluster is still forming? Do the temperature and X-ray brightness of such a distant cluster relate to its mass in the same simple way as they do for nearby clusters?

Source: EurekAlert