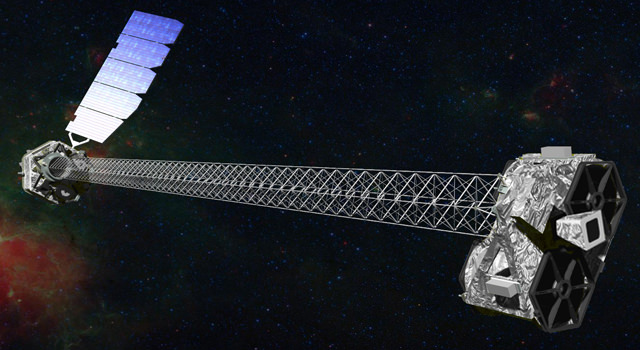

Nine days after launch — and right on schedule — the newest space mission has deployed its unique mast, giving it the ability to see the highest energy X-rays in our universe. The Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array, or NuSTAR, successfully deployed its lengthy 10-meter (33-foot) mast on June 21, and mission scientists say they are one step closer to beginning its hunt for black holes hiding in our Milky Way and other galaxies.

“It’s a real pleasure to know that the mast, an accomplished feat of engineering, is now in its final position,” said Yunjin Kim, the NuSTAR project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Kim was also the project manager for the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, which flew a similar mast on the Space Shuttle Endeavor in 2000 and made topographic maps of Earth.

NuSTAR will search out the most elusive and most energetic black holes, to help in our understanding of the structure of the universe.

NuSTAR has many innovative technologies to allow the telescope to take the first-ever crisp images of high-energy X-ray, and the long mast separates the telescope mirrors from the detectors, providing the distance needed to focus the X-rays.

This is the first deployable mast ever used on a space telescope; the mast was folded up in a small canister during launch.

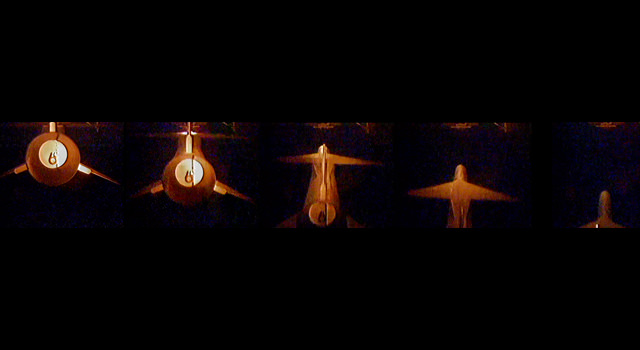

At 10:43 a.m. PDT (1:43 p.m. EDT) engineers at NuSTAR’s mission control at UC Berkeley in California sent a signal to the spacecraft to start extending the mast, a stable, rigid structure consisting of 56 cube-shaped units. Driven by a motor, the mast steadily inched out of a canister as each cube was assembled one by one. The process took about 26 minutes. Engineers and astronomers cheered seconds after they received word from the spacecraft that the mast was fully deployed and secure.

The NuSTAR team will now begin to verify the pointing and motion capabilities of the satellite, and fine-tune the alignment of the mast. In about five days, the team will instruct NuSTAR to take its “first light” pictures, which are used to calibrate the telescope.

Less than 20 days later, science operations are scheduled to begin.

“With its unprecedented spatial and spectral resolution to the previously poorly explored hard X-ray region of the electromagnetic spectrum, NuSTAR will open a new window on the universe and will provide complementary data to NASA’s larger missions, including Fermi, Chandra, Hubble and Spitzer,” said Paul Hertz, NASA’s Astrophysics Division Director.

NuSTAR launched on an Orbital Science Corporation’s Pegasus rocket, which was dropped from a carrier plane, the L-1011 “Stargazer,” also from Orbital.

Lead image caption: Artist’s concept of NuSTAR in orbit. NuSTAR has a 33-foot (10-meter) mast that deploys after launch to separate the optics modules (right) from the detectors in the focal plane (left). Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Source: JPL