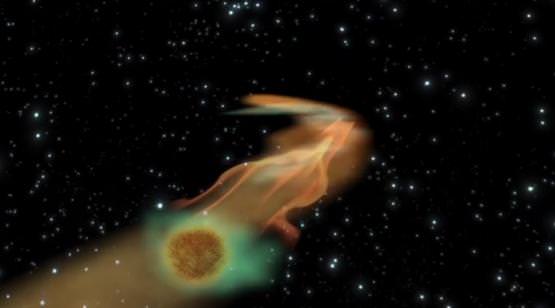

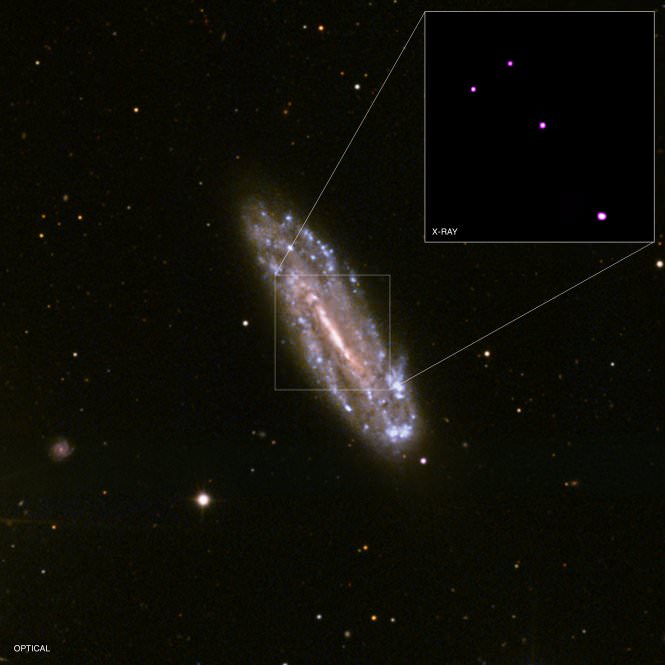

The Hubble image above shows a strange galaxy, known as Mrk 273. The odd shape – including the infrared bright center and the long tail extending into space for 130 thousand light-years – is strongly indicative of a merger between galaxies.

Near-infrared observations have revealed a nucleus with multiple components, but for years the details of such a sight have remained obscured by dust. With further data from the Keck Telescope, based in Hawaii, astronomers have verified that this object is the result of a merger between galaxies, with the infrared bright center consisting of two active galactic nuclei – intensely luminous cores powered by supermassive black holes.

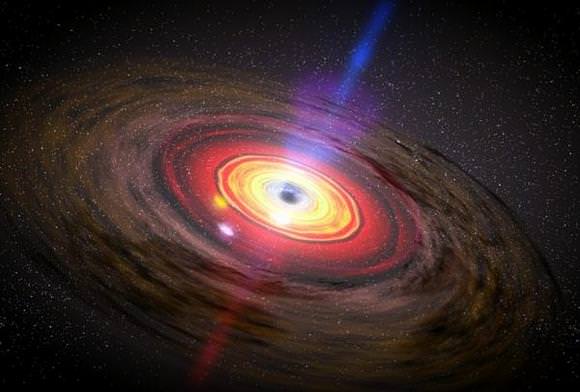

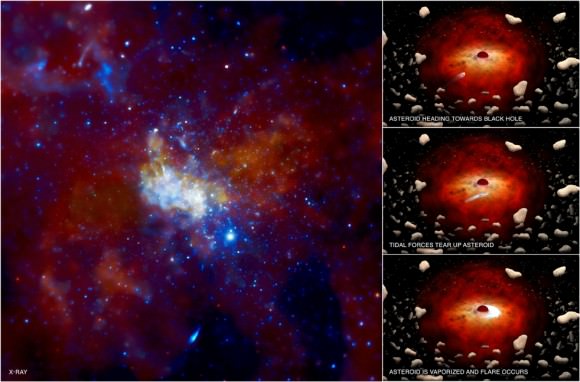

At the center of every single galaxy is a supermassive black hole. While the name sounds exciting, our supermassive black hole, Sgr A* is pretty quiescent. But at the center of every early galaxy looms the opposite: an active galactic nuclei (AGN for short). There are plenty of AGN in the nearby Universe as well, but the question stands: how and when do these black holes become active?

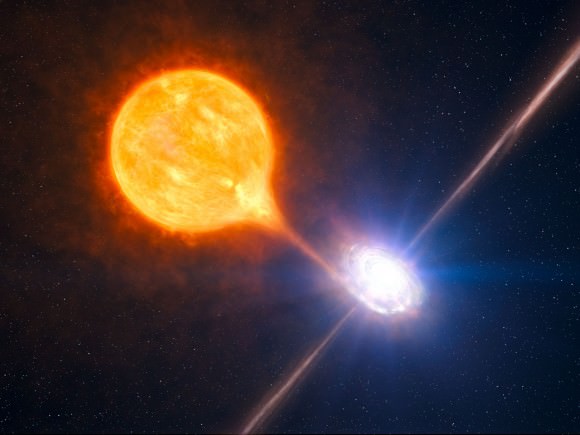

In order to find the answer astronomers are looking at merging galaxies. When two galaxies collide, the supermassive black holes fall toward the center of the merged galaxy, resulting in a binary black hole system. At this stage they remain quiescent black holes, but are likely to become active soon.

“The accretion of material onto a quiescent black hole at the center of a galaxy will enable it to grow in size, leading to the event where the nucleus is “turned on” and becomes active,” Dr. Vivian U, lead author on the study, told Universe Today. “Since galaxy interaction provides means for gaseous material in the progenitor galaxies to lose angular momentum and funnels toward the center of the system, it is thought to play a role in triggering AGN. However, it has been difficult to pinpoint exactly how and when in a merging system this triggering occurs.”

While it has been known that an AGN can “turn on” before the final coalescence of the two black holes, it is unknown as to when this will happen. Quite a few systems do not host dual AGN. For those that do, we do not know whether synchronous ignition occurs or not.

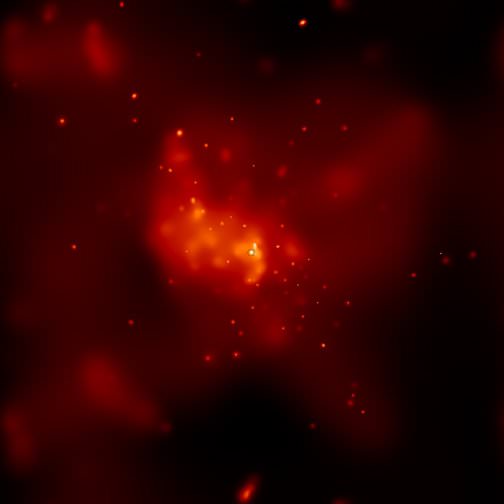

Mrk 273 provides a powerful example to study. The team used near-infrared instruments on the Keck Telescope in order to probe past the dust. Adaptive optics also removed the blurring affects caused by the Earth’s atmosphere, allowing for a much cleaner image – matching the Hubble Space Telescope, from the ground.

“The punch line is that Mrk 273, an advanced late-stage galaxy merger system, hosts two nuclei from the progenitor galaxies that have yet to fully coalesce,” explains Dr. U. The presence of two supermassive black holes can be easily discerned from the rapidly rotating gas disks that surround the two nuclei.

“Both nuclei have already been turned on as evidenced by collimated outflows (a typical AGN signature) that we observe” Dr. U told me. Such a high amount of energy released from both supermassive black holes suggests that Mrk 273 is a dual AGN system. These exciting results mark a crucial step in understanding how galaxy mergers may “turn on” a supermassive black hole.

The team has collected near-infrared data for a large sample of galaxy mergers at different merging states. With the new data set, Dr. U aims “to understand how the nature of the nuclear star formation and AGN activity may change as a galaxy system progresses through the interaction.”

The results will be published in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint available here).