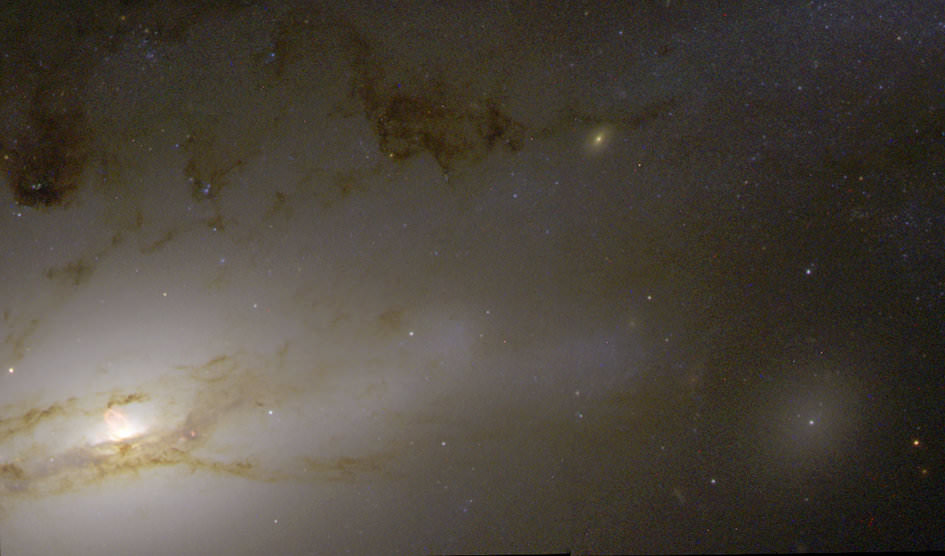

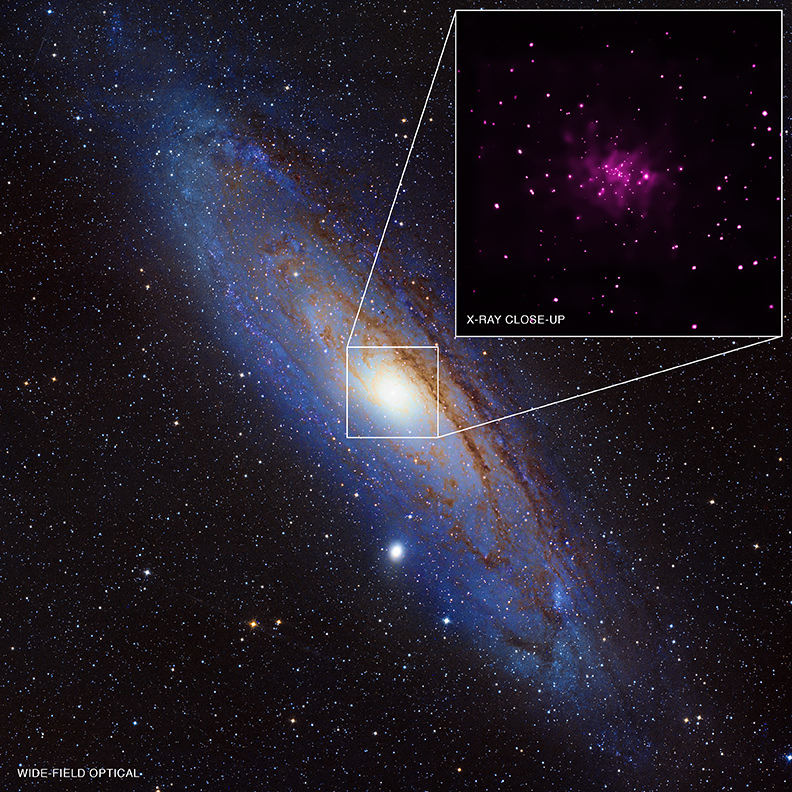

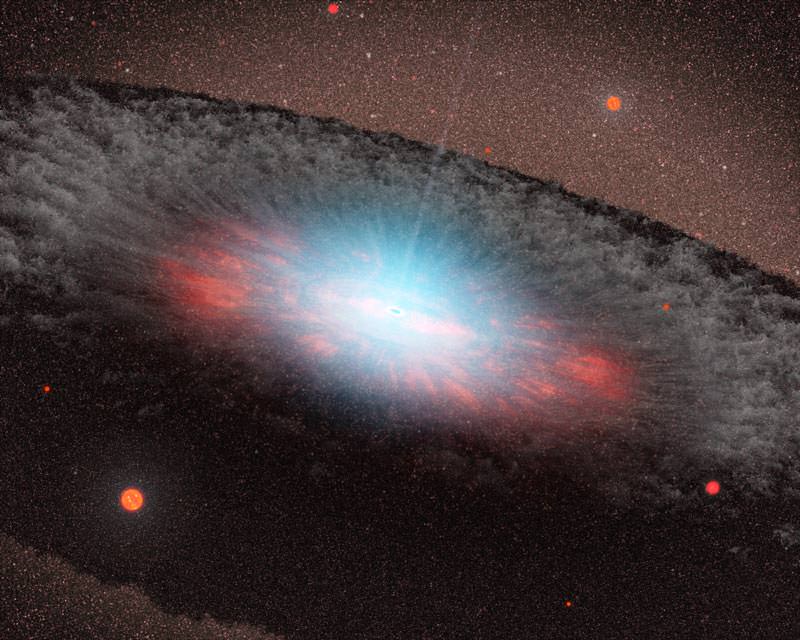

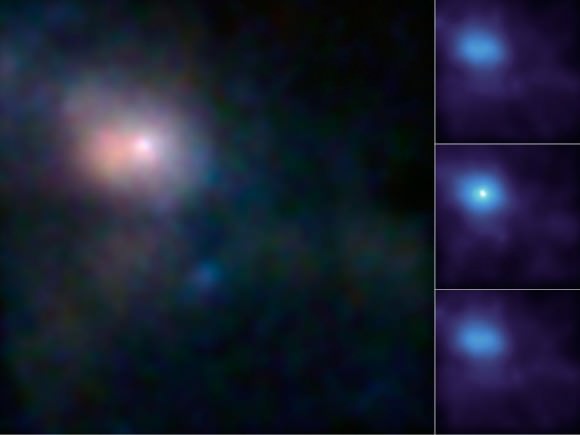

50 million light-years away a quasar resides in the hub of galaxy NGC 4438, an incredibly bright source of light and radiation that’s the result of a supermassive black hole actively feeding on nearby gas and dust (and pretty much anything else that ventures too closely.) Shining with the energy of 1,000 Milky Ways, this quasar — and others like it — are the brightest objects in the visible Universe… so bright, in fact, that they are used as beacons for interplanetary navigation by various exploration spacecraft.

“I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky,And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by.”– John Masefield, “Sea Fever”

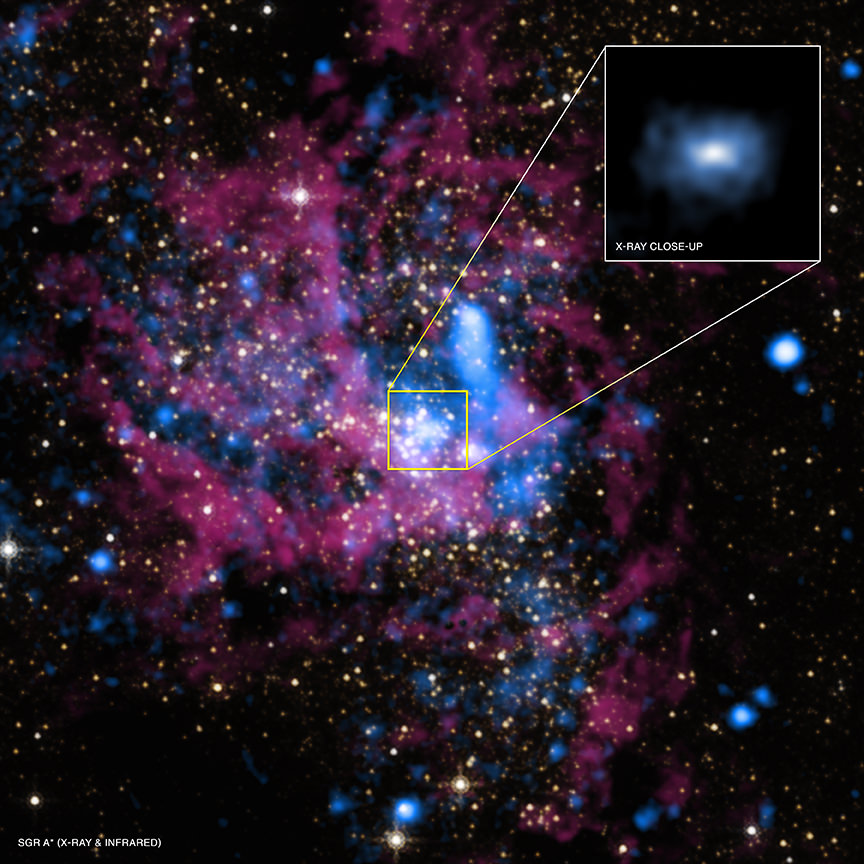

Deep-space missions require precise navigation, especially when approaching bodies such as Mars, Venus, or comets. It’s often necessary to pinpoint a spacecraft traveling 100 million km from Earth to within just 1 km. To achieve this level of accuracy, experts use quasars – the most luminous objects known in the Universe – as beacons in a technique known as Delta-Differential One-Way Ranging, or delta-DOR.

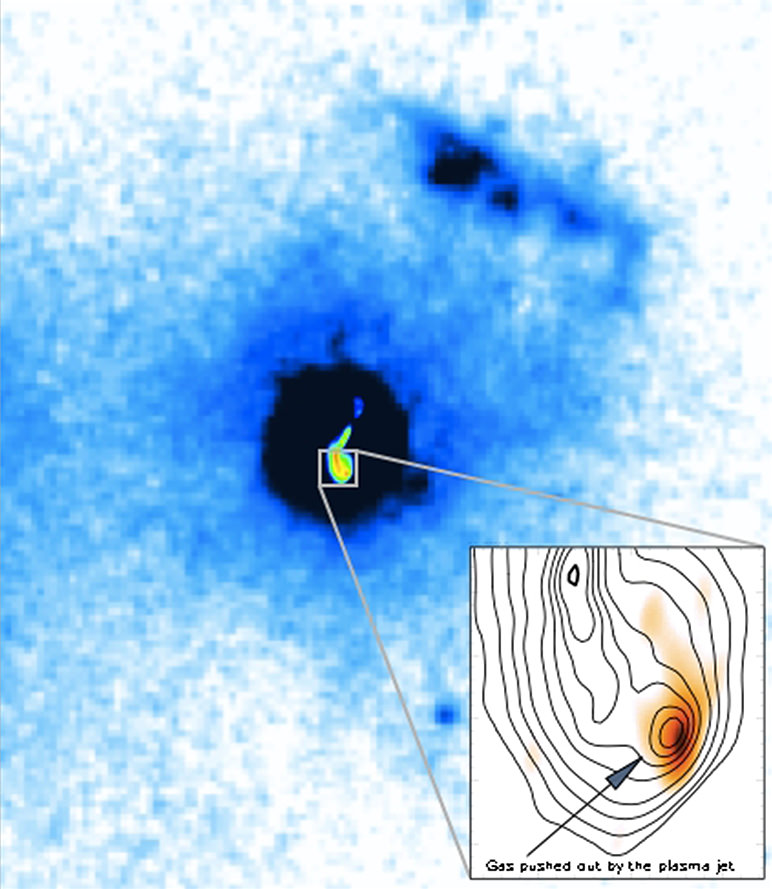

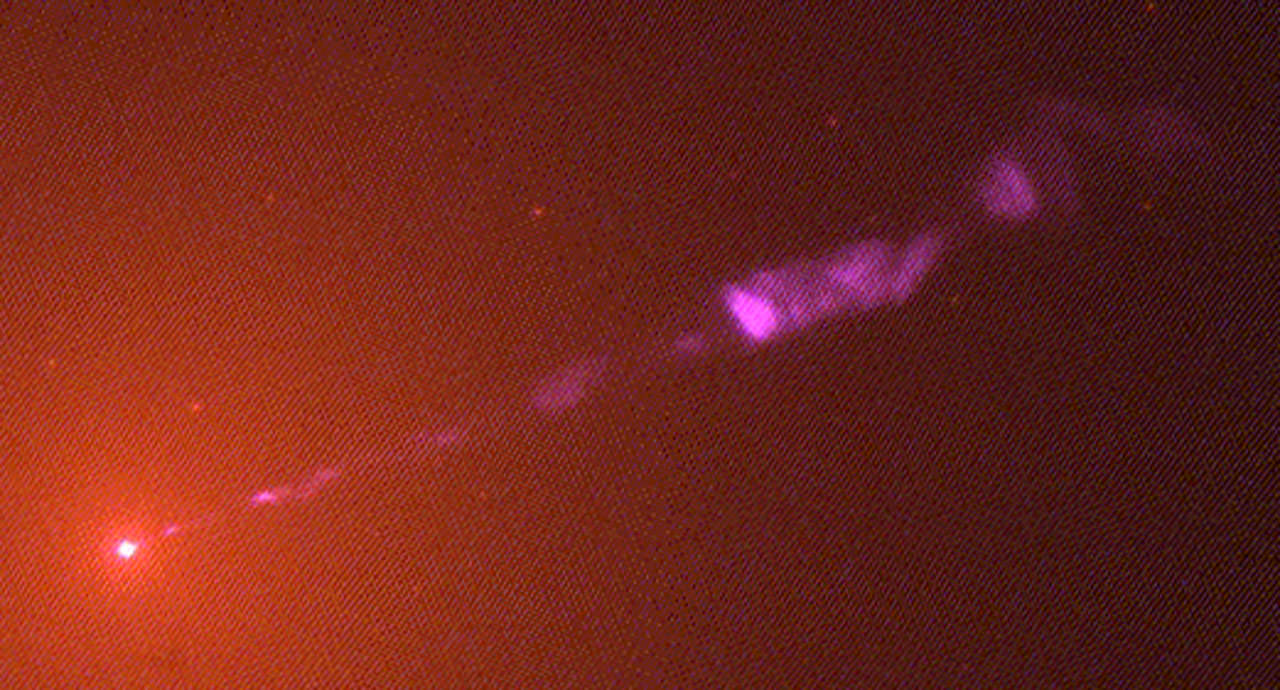

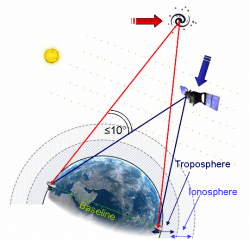

Delta-DOR uses two antennas in distant locations on Earth (such as Goldstone in California and Canberra in Australia) to simultaneously track a transmitting spacecraft in order to measure the time difference (delay) between signals arriving at the two stations.

Unfortunately the delay can be affected by several sources of error, such as the radio waves traveling through the troposphere, ionosphere, and solar plasma, as well as clock instabilities at the ground stations.

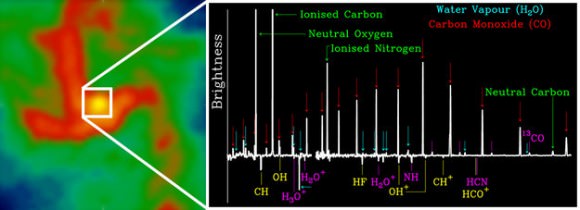

Delta-DOR corrects these errors by tracking a quasar that is located near the spacecraft for calibration — usually within ten degrees. The chosen quasar’s direction is already known extremely well through astronomical measurements, typically to closer than 50 billionths of a degree (one nanoradian, or 0.208533 milliarcsecond). The delay time of the quasar is subtracted from that of the spacecraft’s, providing the delta-DOR measurement and allowing for amazingly high-precision navigation across long distances.

“Quasar locations define a reference system. They enable engineers to improve the precision of the measurements taken by ground stations and improve the accuracy of the direction to the spacecraft to an order of a millionth of a degree.”

– Frank Budnik, ESA flight dynamics expert

So even though the quasar in NGC 4438 is located 50 million light-years from Earth, it can help engineers position a spacecraft located 100 million kilometers away to an accuracy of several hundred meters. Now that’s a star to steer her by!

Read more about Delta-DOR here and here.

Source: ESA Operations