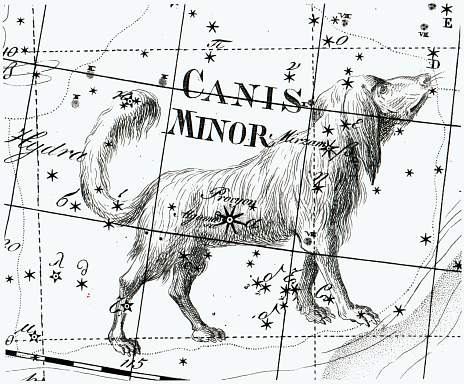

Welcome back to Constellation Friday! Today, in honor of the late and great Tammy Plotner, we will be dealing with the “little dog” – the Canis Minor constellation!

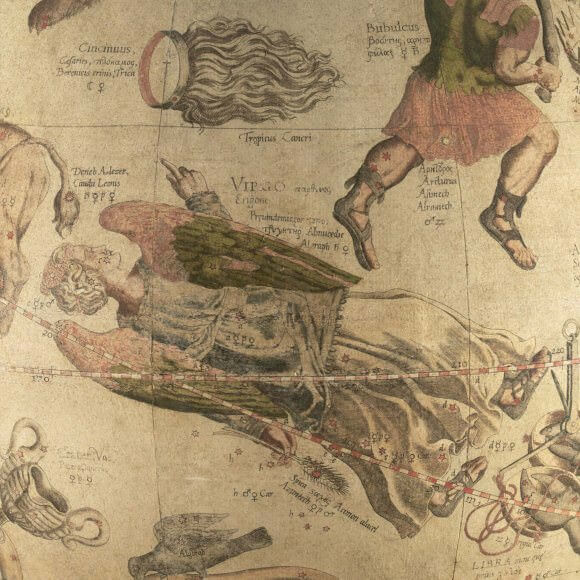

In the 2nd century CE, Greek-Egyptian astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus (aka. Ptolemy) compiled a list of all the then-known 48 constellations. This treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come, effectively becoming astrological and astronomical canon until the early Modern Age.

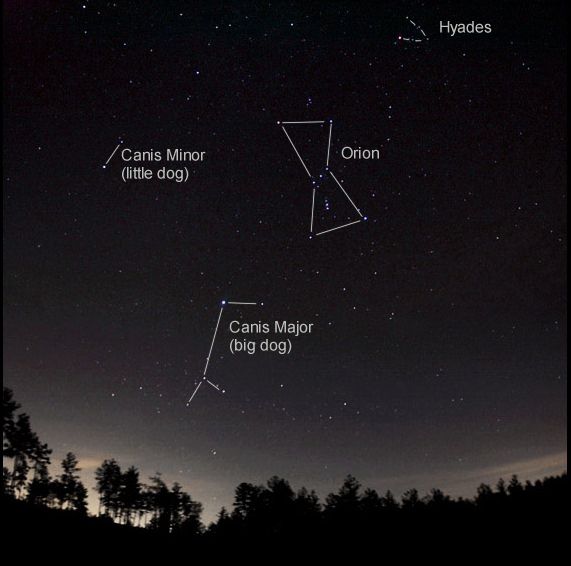

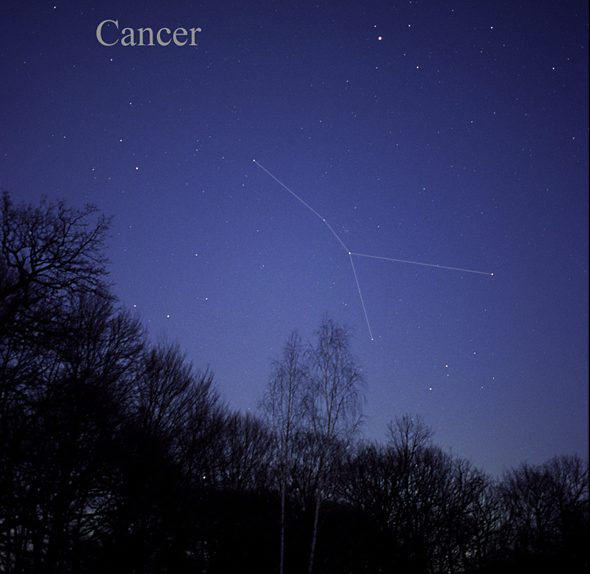

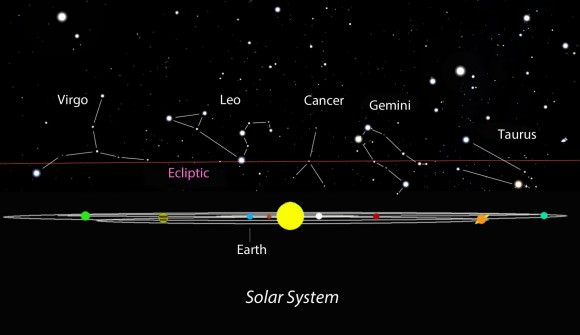

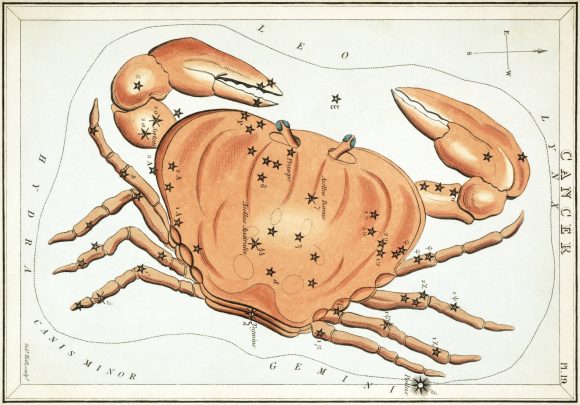

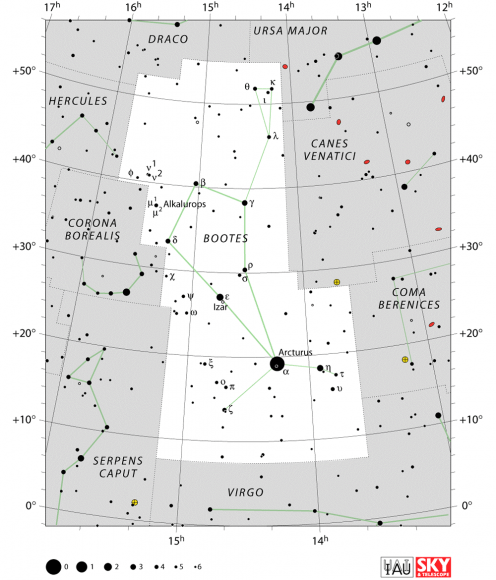

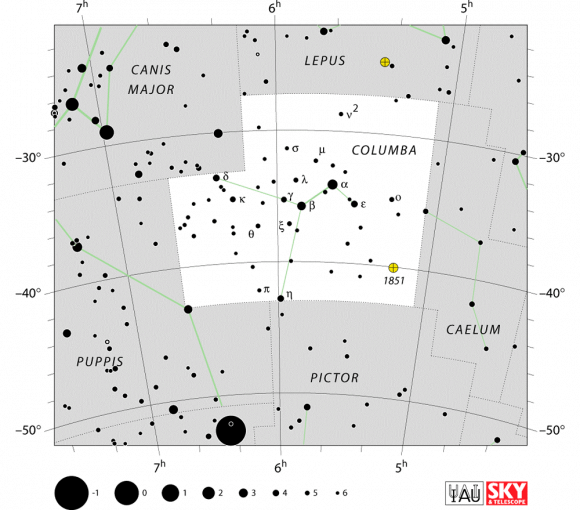

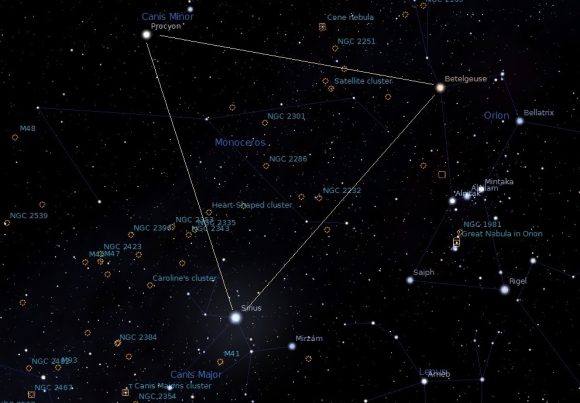

One of these constellations was Canis Minor, a small constellation in the northern hemisphere. As a relatively dim collection of stars, it contains only two particularly bright stars and only faint Deep Sky Objects. Today, it is one of the 88 constellations recognized by the International Astronomical Union, and is bordered by the Monoceros, Gemini, Cancer and Hydra constellation.

Name and Meaning:

Like most asterisms named by the Greeks and Romans, the first recorded mention of this constellation goes back to ancient Mesopotamia. Specifically, Canis Minor’s brightest stars – Procyon and Gomeisa – were mentioned in the Three Stars Each tablets (ca. 1100 BCE), where they were referred to as MASH.TAB.BA (or “twins”).

In the later texts that belong to the MUL.APIN, the constellation was given the name DAR.LUGAL (“the star which stands behind it”) and represented a rooster. According to ancient Greco-Roman mythology, Canis Minor represented the smaller of Orion’s two hunting dogs, though they did not recognize it as its own constellation.

In Greek mythology, Canis Minor is also connected with the Teumessian Fox, a beast turned into stone with its hunter (Laelaps) by Zeus. He then placed them in heaven as Canis Major (Laelaps) and Canis Minor (Teumessian Fox). According to English astronomer and biographer of constellation history Ian Ridpath:

“Canis Minor is usually identified as one of the dogs of Orion. But in a famous legend from Attica (the area around Athens), recounted by the mythographer Hyginus, the constellation represents Maera, dog of Icarius, the man whom the god Dionysus first taught to make wine. When Icarius gave his wine to some shepherds for tasting, they rapidly became drunk. Suspecting that Icarius had poisoned them, they killed him. Maera the dog ran howling to Icarius’s daughter Erigone, caught hold of her dress with his teeth and led her to her father’s body. Both Erigone and the dog took their own lives where Icarius lay.

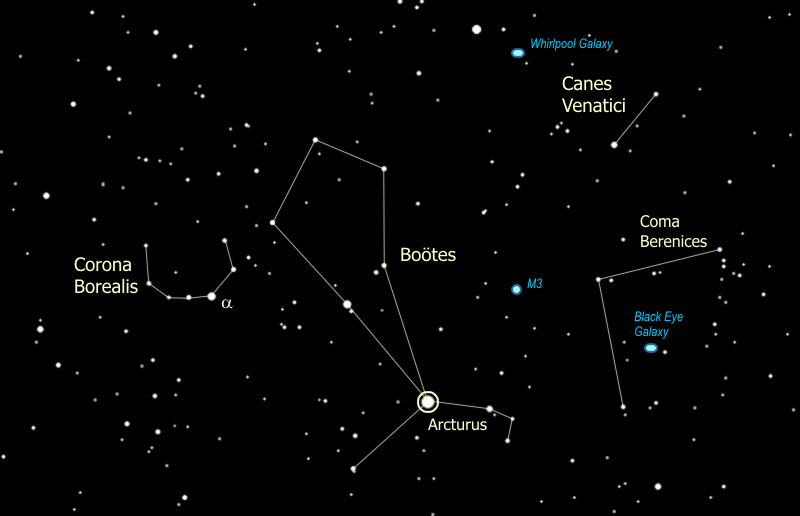

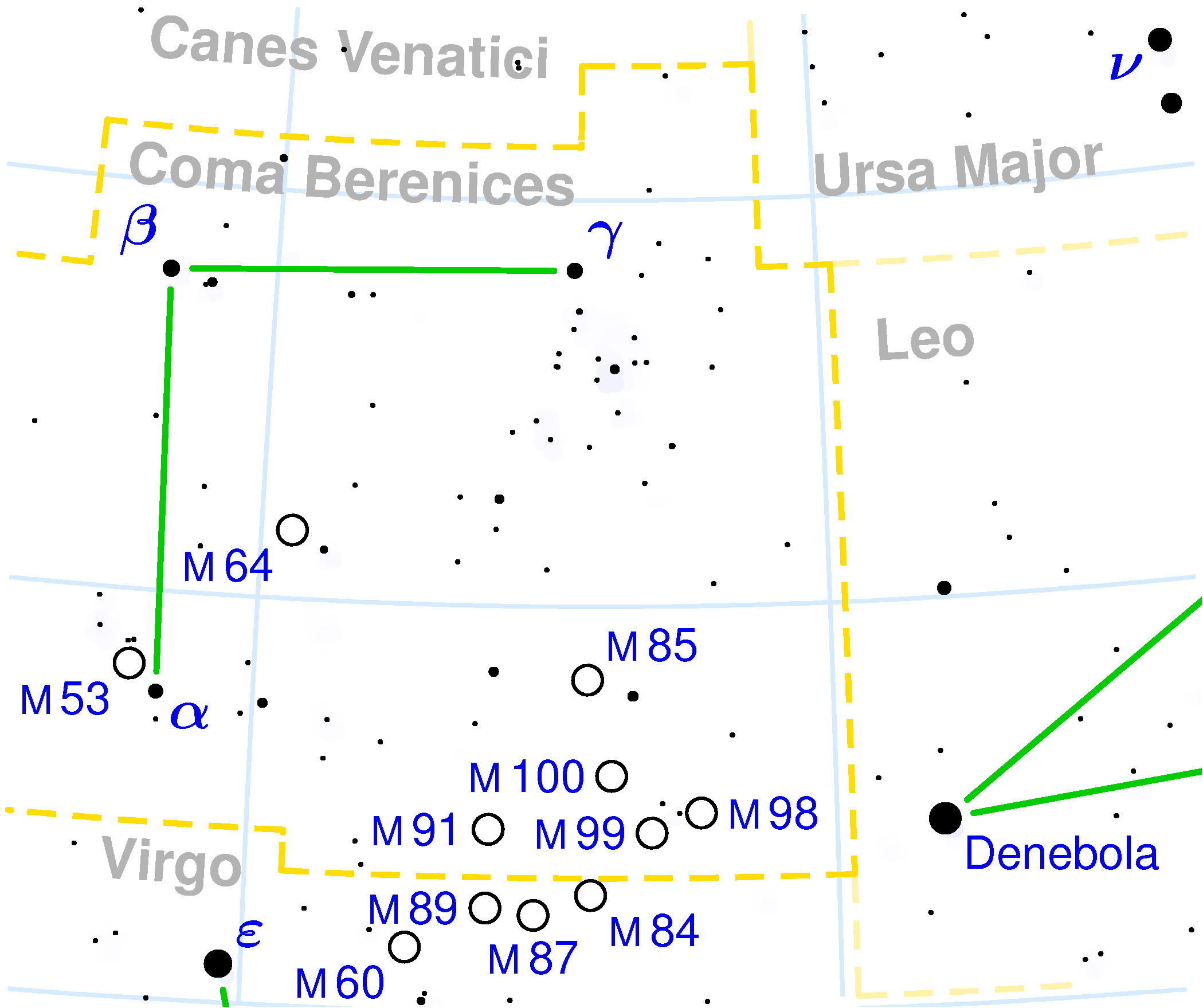

“Zeus placed their images among the stars as a reminder of the unfortunate affair. To atone for their tragic mistake, the people of Athens instituted a yearly celebration in honour of Icarius and Erigone. In this story, Icarius is identified with the constellation Boötes, Erigone is Virgo and Maera is Canis Minor.”

To the ancient Egyptians, this constellation represented Anubis, the jackal god. To the ancient Aztecs, the stars of Canis Minor were incorporated along with stars from Orion and Gemini into as asterism known as “Water”, which was associated with the day. Procyon was also significant in the cultural traditions of the Polynesians, the Maori people of New Zealand, and the Aborigines of Australia.

In Chinese astronomy, the stars corresponding to Canis Minor were part of the The Vermilion Bird of the South. Along with stars from Cancer and Gemini, they formed the asterisms known as the Northern and Southern River, as well as the asterism Shuiwei (“water level”), which represented an official who managed floodwaters or a marker of the water level.

History of Observation:

Canis Minor was one of the original 48 constellations included by Ptolemy in his the Almagest. Though not recognized as its own asterism by the Ancient Greeks, it was added by the Romans as the smaller of Orion’s hunting dogs. Thanks to Ptolemy’s inclusion of it in his 2nd century treatise, it would go on to become part of astrological and astronomical traditions for a thousand years to come.

For medieval Arabic astronomers, Canis Minor continued to be depicted as a dog, and was known as “al-Kalb al-Asghar“. It was included in the Book of Fixed Stars by Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi, who assigned a canine figure to his stellar diagram. Procyon and Gomeisa were also named for their proximity to Sirius; Procyon being named the “Syrian Sirius (“ash-Shi’ra ash-Shamiya“) and Gomeisa the “Sirius with bleary eyes” (“ash-Shira al-Ghamisa“).

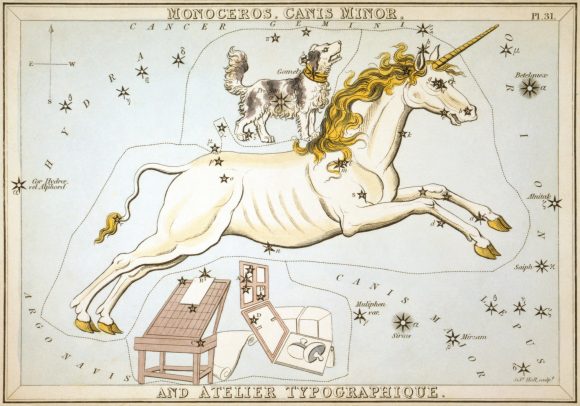

The constellation was included in Syndey Hall’s Urania’s Mirror (1825) alongside Monoceros and the now obsolete constellation Atelier Typographique. Many alternate names were suggested between the 17th and 19th centuries in an attempt to simplify celestial charts. However, Canis Minor has endured; and in 1922, it became one the 88 modern constellations to be recognized by the IAU.

Notable Features:

Canis Minor contains two primary stars and 14 Bayer/Flamsteed designated stars. It’s brightest star, Procyon (Alpha Canis Minoris), is also the seventh brightest star in the sky. With an apparent visual magnitude of 0.34, Procyon is not extraordinarily bright in itself. But it’s proximity to the Sun – 11.41 light years from Earth – ensures that it appears bright in the night sky.

The star’s name is derived from the Greek word which means “before the dog”, a reference to the fact that it appears to rise before Sirius (the “Dog Star”) when observed from northern latitudes. Procyon is a binary star system, composed of a white main sequence star (Procyon A) and Procyon B, a DA-type faint white dwarf as the companion.

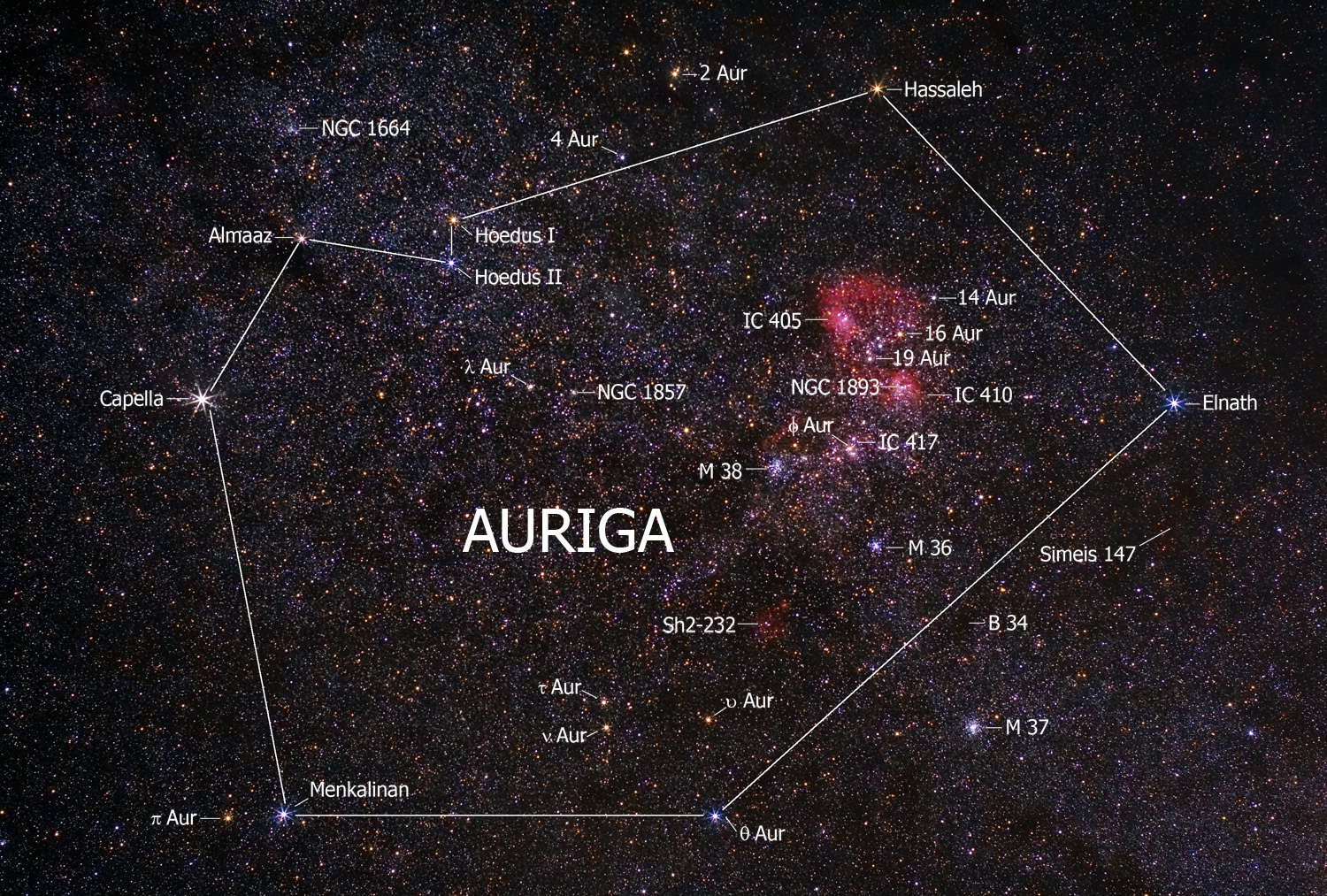

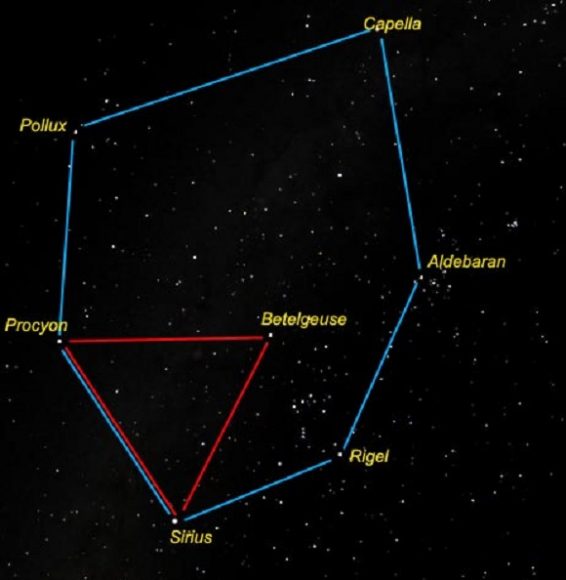

Procyon is part of the Winter Triangle asterism, along with Sirius in Canis Major and Betelgeuse in the constellation Orion. It is also part of the Winter Hexagon, along with the stars Capella in Auriga, Aldebaran in Taurus, Castor and Pollux in Gemini, Rigel in Orion and Sirius in Canis Major.

Next up is Gomeisa, the second brightest star in Canis Minor. This hot, B8-type main sequence star is classified as a Gamma Cassiopeiae variable, which means that it rotates rapidly and exhibits irregular variations in luminosity because of the outflow of matter. Gomeisa is approximately 170 light years from Earth and the name is derived from the Arabic “al-ghumaisa” (“the bleary-eyed woman”).

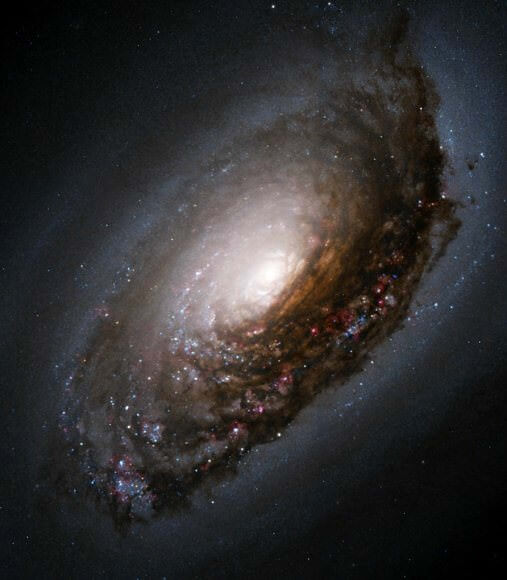

Canis Minor also has a number of Deep Sky Objects located within it, but all are very faint and difficult to observe. The brightest is the spiral galaxy NGC 2485 (apparent magnitude of 12.4), which is located 3.5 degrees northeast of Procyon. There is one meteor shower associated with this constellation, which are the Canis-Minorids.

Finding Canis Minor:

Though it is relatively faint, Canis Minor and its stars can be viewed using binoculars. Start with the brightest, Procyon – aka. Alpha Canis Minoris (Alpha CMi). If you’re unsure of which bright star is, you’ll find it in the center of the diamond shape grouping in the southwest area. Known to the ancients as Procyon – “The Little Dog Star” – it’s the seventh brightest star in the night sky and the 13th nearest to our solar system.

For over 100 years, astronomers have known this brilliant star had a companion. Being 15,000 times fainter than the parent star, Procyon B is an example of a white dwarf whose diameter is only about twice that of Earth. But its density exceeds two tons per cubic inch! (Or, a third of a metric ton per cubic centimeter). While only very large telescopes can resolve this second closest of the white dwarf stars, even the moonlight can’t dim its beauty.

Now hop over to Beta CMi. Known by the very strange name of Gomeisa (“bleary-eyed woman”), it refers to the weeping sister left behind when Sirius and Canopus ran to the south to save their lives. Located about 170 light years away from our Solar System, Beta is a blue-white class B main sequence dwarf star with around 3 times the mass of our Sun and a stellar luminosity over 250 times that of Sol.

Gomeisa is a fast rotator, spinning at its equator with a speed of at least 250 kilometers per second (125 times our Sun’s rotation speed) giving the star a rotation period of about a day. Sunspots would appear to move very quickly there! According to Jim Kaler, Professor Emeritus of Astronomy at the University of Illinois:

“Since we may be looking more at the star’s pole than at its equator, it may be spinning much faster, and indeed is rotating so quickly that it is surrounded by a disk of matter that emits radiation, rendering Gomeisa a “B-emission” star rather like Gamma Cassiopeiae and Alcyone. Like these two, Gomeisa is distinguished by having the size of its disk directly measured, the disk’s diameter almost four times larger than the star. Like quite a number of hot stars (including Adhara, Nunki, and many others), Gomeisa is also surrounded by a thin cloud of dusty interstellar gas that it helps to heat.”

Now hop over to Gamma Canis Minoris, an orange K-type giant with an apparent magnitude of +4.33. It is a spectroscopic binary, has an unresolved companion which has an orbital period of 389 days, and is approximately 398 light years from Earth. And next is Epsilon Canis Minoris, a yellow G-type bright giant (apparent magnitude of +4.99) which is approximately 990 light years from Earth.

For smaller telescopes, the double star Struve 1149 is a lovely sight, consisting of a yellow primary star and a faintly blue companion. For larger telescopes and GoTo telescopes, try NGC 2485 (RA 07 56.7 Dec +07 29), a magnitude 13 spiral galaxy that has a small, round glow, sharp edges and a very bright, stellar nucleus. If you want one that’s even more challenging, try NGC 2508 (RA 08 02 0 Dec +08 34).

Canis Minor lies in the second quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ2) and can be seen at latitudes between +90° and -75°. The neighboring constellations are Cancer, Gemini, Hydra, and Monoceros, and it is best visible during the month of March.

We have written many interesting articles about the constellation here at Universe Today. Here is What Are The Constellations?, What Is The Zodiac?, and Zodiac Signs And Their Dates.

Be sure to check out The Messier Catalog while you’re at it!

For more information, check out the IAUs list of Constellations, and the Students for the Exploration and Development of Space page on Canes Venatici and Constellation Families.

Sources: