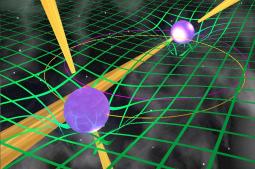

Einstein’s theory of General Relativity has been around for 93 years, and it just keeps hanging in there. With advances in technology has come the ability to put the theory under some scrutiny. Recently, taking advantage of a unique cosmic coincidence, as well as a pretty darn good telescope, astronomers looked at the strong gravity from a pair of superdense neutron stars and measured an effect predicted by General Relativity. The theory came through with flying colors.

Einstein’s 1915 theory predicted that in a close system of two very massive objects, such as neutron stars, one object’s gravitational tug, along with an effect of its spinning around its axis, should cause the spin axis of the other to wobble, or precess. Studies of other pulsars in binary systems had indicated that such wobbling occurred, but could not produce precise measurements of the amount of wobbling.

“Measuring the amount of wobbling is what tests the details of Einstein’s theory and gives a benchmark that any alternative gravitational theories must meet,” said Scott Ransom of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

The astronomers used the National Science Foundation’s Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope (GBT) to make a four-year study of a double-star system unlike any other known in the Universe. The system is a pair of neutron stars, both of which are seen as pulsars that emit lighthouse-like beams of radio waves.

“Of about 1700 known pulsars, this is the only case where two pulsars are in orbit around each other,” said Rene Breton, a graduate student at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. In addition, the stars’ orbital plane is aligned nearly perfectly with their line of sight to the Earth, so that one passes behind a doughnut-shaped region of ionized gas surrounding the other, eclipsing the signal from the pulsar in back.

Animation of double pulsar system

The eclipses allowed the astronomers to pin down the geometry of the double-pulsar system and track changes in the orientation of the spin axis of one of them. As one pulsar’s spin axis slowly moved, the pattern of signal blockages as the other passed behind it also changed. The signal from the pulsar in back is absorbed by the ionized gas in the other’s magnetosphere.

The pair of pulsars studied with the GBT is about 1700 light-years from Earth. The average distance between the two is only about twice the distance from the Earth to the Moon. The two orbit each other in just under two and a half hours.

“A system like this, with two very massive objects very close to each other, is precisely the kind of extreme ‘cosmic laboratory’ needed to test Einstein’s prediction,” said Victoria Kaspi, leader of McGill University’s Pulsar Group.

Theories of gravity don’t differ significantly in “ordinary” regions of space such as our own Solar System. In regions of extremely strong gravity fields, such as near a pair of close, massive objects, however, differences are expected to show up. In the binary-pulsar study, General Relativity “passed the test” provided by such an extreme environment, the scientists said.

“It’s not quite right to say that we have now ‘proven’ General Relativity,” Breton said. “However, so far, Einstein’s theory has passed all the tests that have been conducted, including ours.”

Original News Source: Jodrell Bank Observatory