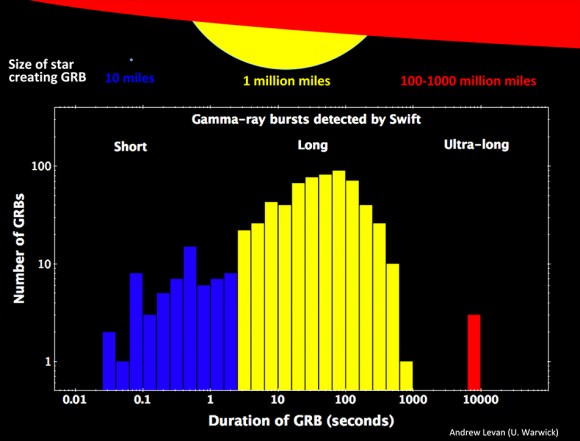

According to astronomer Andrew Levan, there’s an old adage in studying gamma ray bursts: “When you’ve seen one gamma ray burst, you’ve seen … only one gamma ray burst. They aren’t all the same,” he said during a press briefing on April 16 discussing the discovery of a very different kind of GRB – a type that comes in a new long-lasting flavor.

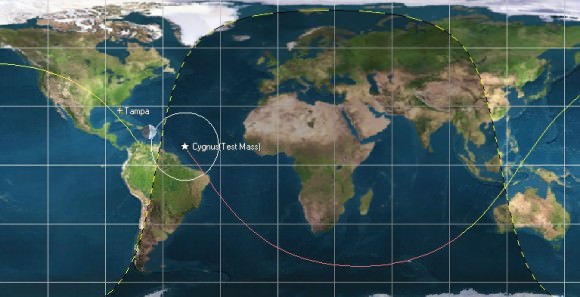

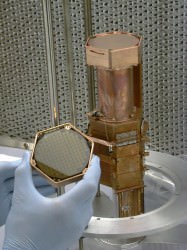

Three of these unusual long-lasting stellar explosions have recently been discovered using the Swift satellite and other international telescopes, and one, named GRB 111209A, is the longest GRB ever observed, with a duration of at least 25,000 seconds, or about 7 hours.

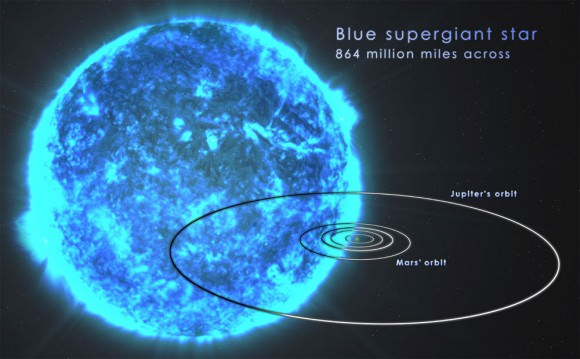

“We have observed the longest gamma ray burst in modern history, and think this event is caused by the death of a blue supergiant,” said Bruce Gendre, a researcher now associated with the French National Center for Scientific Research who led this study while at the Italian Space Agency’s Science Data Center in Frascati, Italy. “It caused the most powerful stellar explosion in recent history, and likely since the Big Bang occurred.”

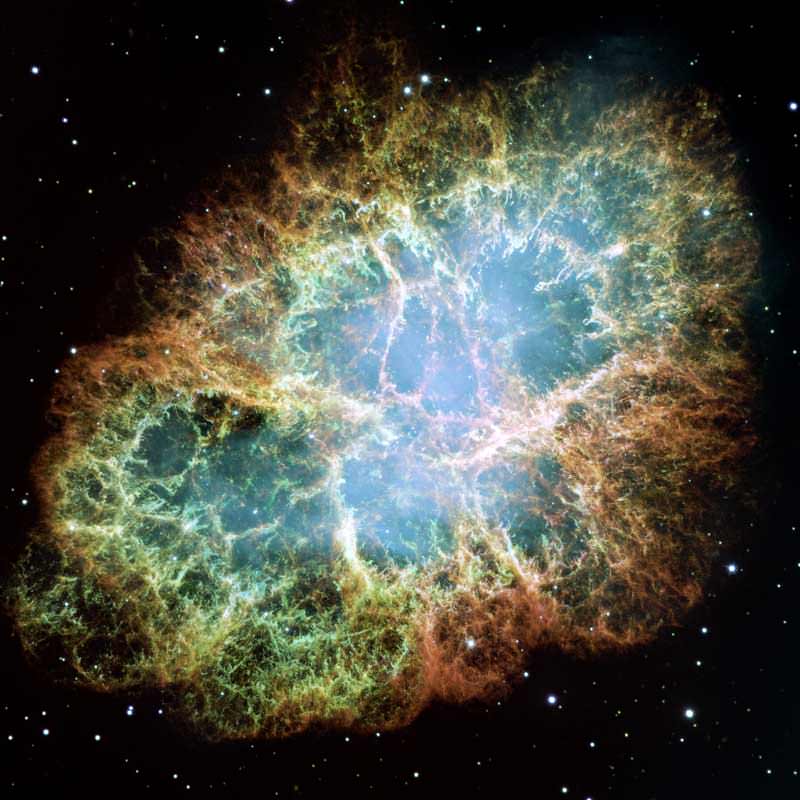

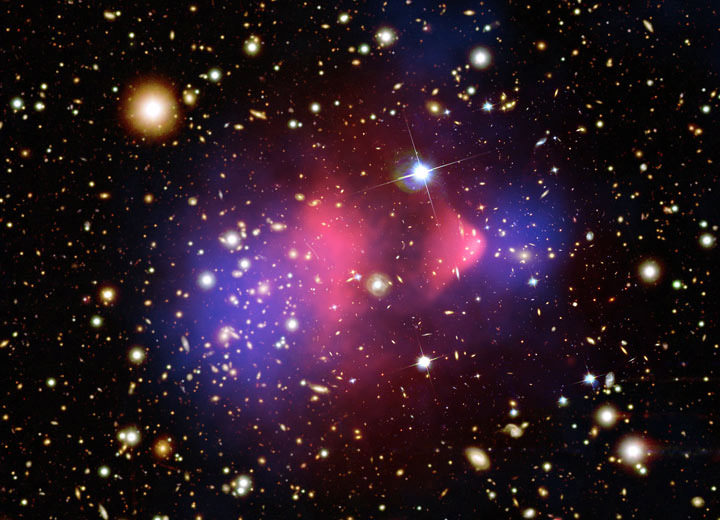

The astronomers said these three GRBs represent a previously unrecognized class of these stellar explosions, which arise from the catastrophic deaths of supergiant stars hundreds of times larger than our Sun. GRBs are the most luminous and mysterious explosions in the Universe. The blasts emit surges of gamma rays — the most powerful form of light — as well as X-rays, and they produce afterglows that can be observed at optical and radio energies.

Swift, the Fermi telescope and other spacecraft detect an average of about one GRB each day. As to why this type of GRB hasn’t been detected before, Levan explained this new type appears to be difficult to find because of how long they last.

“Gamma ray telescopes usually detect a quick spike, and you look for a burst — at how many gamma rays come from the sky,” Levan told Universe Today. “But these new GRBs put out energy over a long period of time, over 10,000 seconds instead of the usual 100 seconds. Because it is spread out, it is harder to spot, and only since Swift launched do we have the ability to build up images of GBSs across the sky. To detect this new kind, you have to add up all the light over a long period of time.”

Levan is an astronomer at the University of Warwick in Coventry, England.

He added that these long-lasting GRBs were likely more common in the Universe’s past.

Traditionally, astronomers have recognized two types of GRBs: short and long, based on the duration of the gamma-ray signal. Short bursts last two seconds or less and are thought to represent a merger of compact objects in a binary system, with the most likely suspects being neutron stars and black holes. Long GRBs may last anywhere from several seconds to several minutes, with typical durations falling between 20 and 50 seconds. These events are thought to be associated with the collapse of a star many times the Sun’s mass and the resulting birth of a new black hole.

“It’s a very random process and every GRB looks very different,” said Levan during the briefing. “They all have a range of durations and a range of energies. It will take much bigger sample to see if this new type have more complexities than regular gamma rays bursts.”

All GRBs give rise to powerful jets that propel matter at nearly the speed of light in opposite directions. As they interact with matter in and around the star, the jets produce a spike of high-energy light.

Gendre and his colleagues made a detailed study of GRB 111209A, which erupted on Dec. 9, 2011, using gamma-ray data from the Konus instrument on NASA’s Wind spacecraft, X-ray observations from Swift and the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton satellite, and optical data from the TAROT robotic observatory in La Silla, Chile. The 7-hour burst is by far the longest-duration GRB ever recorded.

Another event, GRB 101225A, exploded on December 25, 2010 and produced high-energy emission for at least two hours. Subsequently nicknamed the “Christmas burst,” the event’s distance was unknown, which led two teams to arrive at radically different physical interpretations. One group concluded the blast was caused by an asteroid or comet falling onto a neutron star within our own galaxy. Another team determined that the burst was the outcome of a merger event in an exotic binary system located some 3.5 billion light-years away.

“We now know that the Christmas burst occurred much farther off, more than halfway across the observable universe, and was consequently far more powerful than these researchers imagined,” said Levan.

Using the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii, Levan and his team obtained a spectrum of the faint galaxy that hosted the Christmas burst. This enabled the scientists to identify emission lines of oxygen and hydrogen and determine how much these lines were displaced to lower energies compared to their appearance in a laboratory. This difference, known to astronomers as a redshift, places the burst some 7 billion light-years away.

Levan’s team also examined 111209A and the more recent burst 121027A, which exploded on Oct. 27, 2012. All show similar X-ray, ultraviolet and optical emission and all arose from the central regions of compact galaxies that were actively forming stars. The astronomers have concluded that all three GRBs constitute a new kind of GRB, which they are calling “ultra-long” bursts.

“Ultra-long GRBs arise from very large stars,” said Levan, “perhaps as big as the orbit of Jupiter. Because the material falling onto the black hole from the edge of the star has further to fall it takes longer to get there. Because it takes longer to get there, it powers the jet for a longer time, giving it time to break out of the star.”

Levan said that Wolf-Rayet stars best fit the description. “They are born with more than 25 times the Sun’s mass, but they burn so hot that they drive away their deep, outermost layer of hydrogen as an outflow we call a stellar wind,” he said. Stripping away the star’s atmosphere leaves an object massive enough to form a black hole but small enough for the particle jets to drill all the way through in times typical of long GRBs

John Graham and Andrew Fruchter, both astronomers at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, provided details that these blue supergiant contain relatively modest amounts of elements heavier than helium, which astronomers call metals. This fits an apparent puzzle piece, that these ultra-long GRBs seem to have a strong intrinsic preference for low metallicity environments that contain just trace amounts of elements other than hydrogen and helium.

“High metalicity long duration GRBs do exist but are rare,” said Graham. “They occur at about 1/25th the rate (per unit of star formation) of the low metallicity events. This is good news for us here on Earth, as the likelihood of this type of GRB going off in our own galaxy is far less than previously thought.”

The astronomers discussed their findings Tuesday at the 2013 Huntsville Gamma-ray Burst Symposium in Nashville, Tenn., a meeting sponsored in part by the University of Alabama at Huntsville and NASA’s Swift and Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope missions. Gendre’s findings appear in the March 20 edition of The Astrophysical Journal.

Paper: “The Ultra-long Gamma-Ray Burst 111209A: The Collapse of a Blue Supergiant?” B. Genre et al.

Paper: “The Metal Aversion of LGRBs.” J. F. Graham and A. S. Fruchter.

Sources: Teleconference, NASA, University of Warwick, CNRS