[/caption]

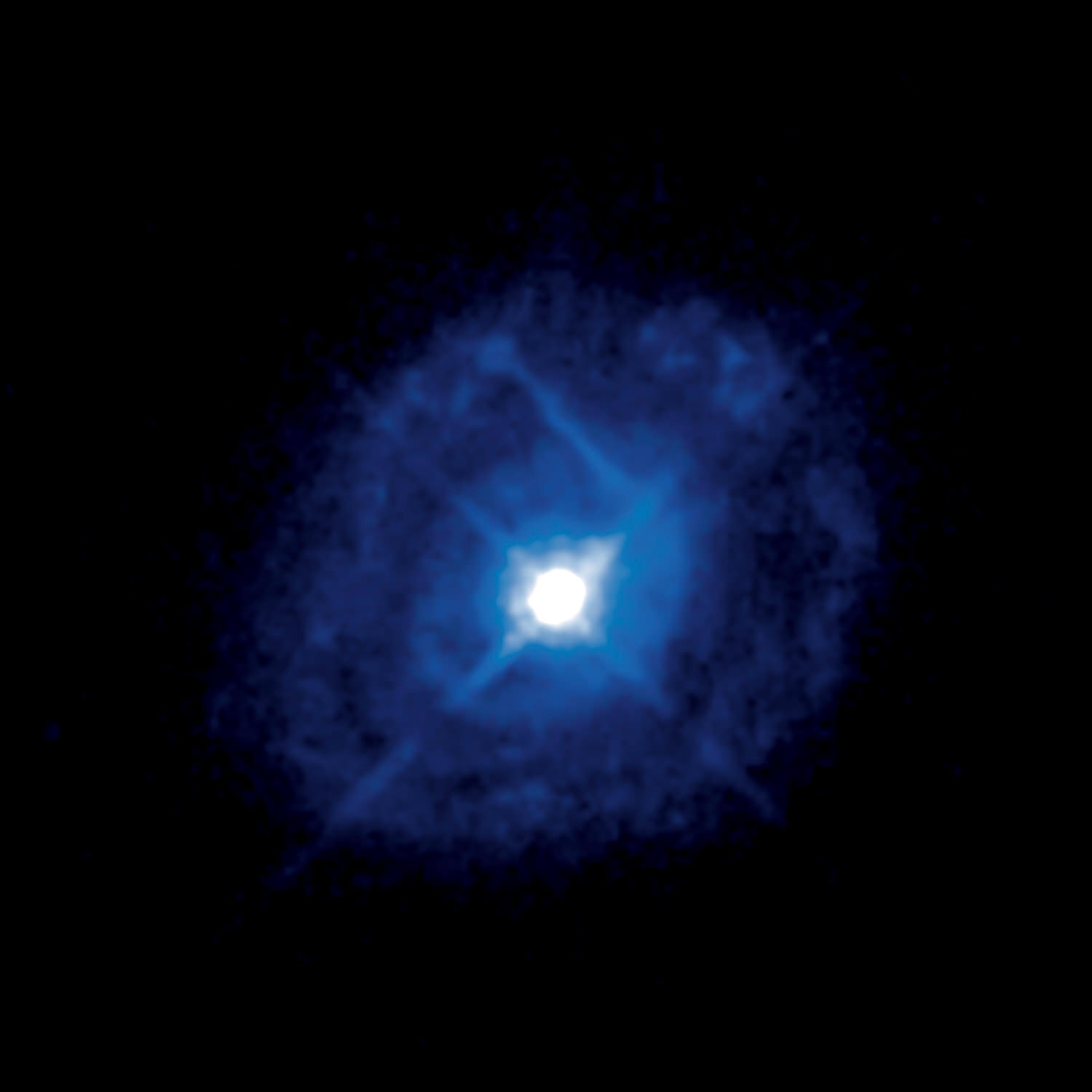

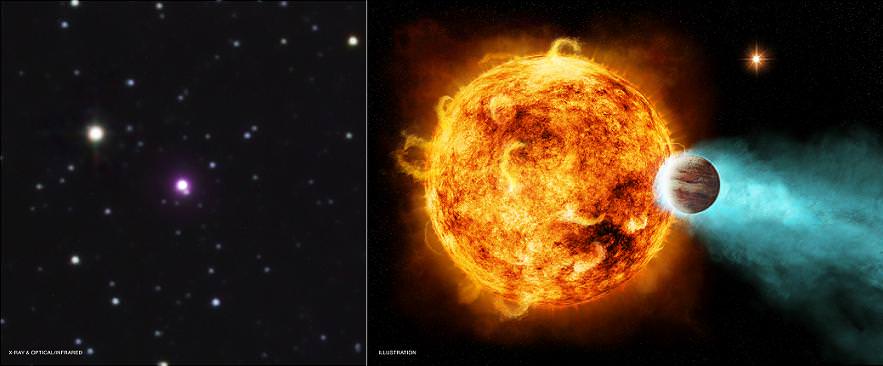

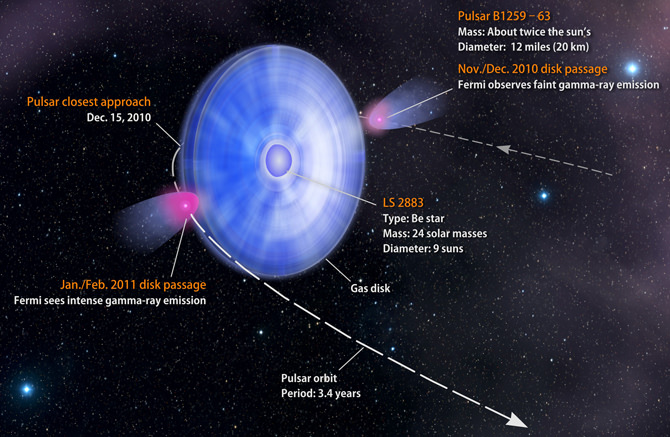

It’s a gamma-ray flare – the most extreme form of light so far known. So, what could top it? Try a pair of gamma-ray flares. Way off in the southern constellation of Crux, an extreme team of stars gave a real show to NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. In December 2010, they blew past each other at about the distance Venus orbits our Sun. Why was this encounter so unique? Because one member was hot and blue/white… and the other a pulsar.

“Even though we were waiting for this event, it still surprised us,” said Aous Abdo, a Research Assistant Professor at George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., and a leader of the research team.

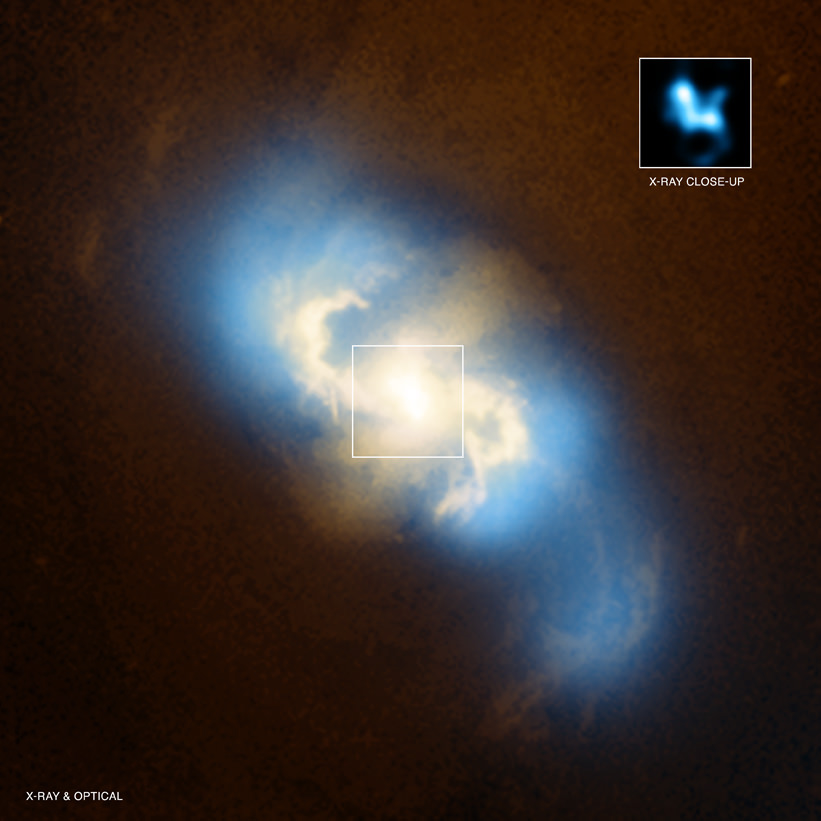

Astronomers were aware that PSR B1259-63 and LS 2883 made a close pass to each other about every 3 to 4 years and were eagerly anticipating the action. Residing at about 8,000 light years away, the signature signal from PSR B1259-63 was discovered in 1989 by the Parkes radio telescope in Australia. It is suspected to be quite small – about the size of Washington, DC and weighs about twice as much as Sol. What’s cool is it rotates at a dizzying 21 times per second… shooting of a powerful beam of electromagnetic energy that sweeps around like a search light. Next door the blue/white companion star lay embedded in gas, measuring in about 9 times larger size and weighing in at about 24 solar masses. Of these “odd couples” only four are known to produce gamma-rays and only this particular system is known to contain a pulsar… one that punches through the gas disk both coming and going during orbit.

“During these disk passages, energetic particles emitted by the pulsar can interact with the disk, and this can lead to processes that accelerate particles and produce radiation at different energies,” said study co-author Simon Johnston of the Australia Telescope National Facility in Epping, New South Wales. “The frustrating thing for astronomers is that the pulsar follows such an eccentric orbit that these events only happen every 3.4 years.”

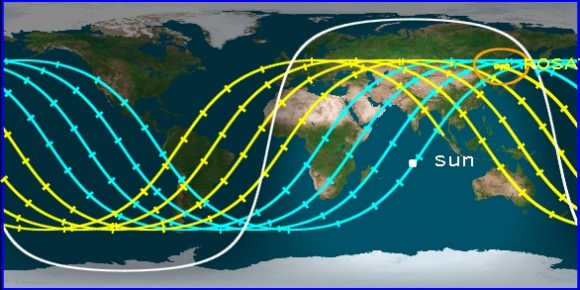

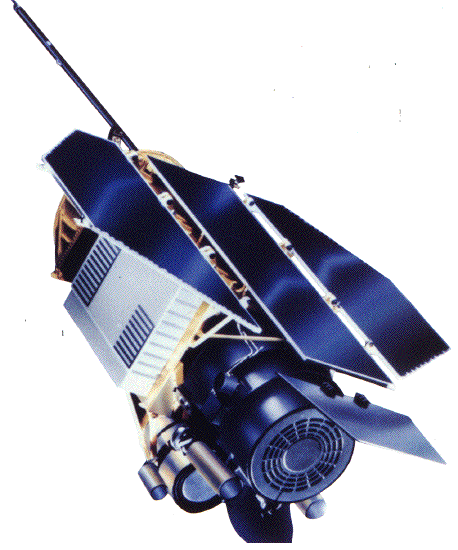

On December 15, 2010, all “eyes” and “ears” were turned the system’s way in anticipation of the dual gamma-ray burst. The observatories included Fermi and NASA’s Swift spacecraft; the European space telescopes XMM-Newton and INTEGRAL; the Japan-U.S. Suzaku satellite; the Australia Telescope Compact Array; optical and infrared telescopes in Chile and South Africa; and the High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.), a ground-based observatory in Namibia that can detect gamma rays with energies of trillions of electron volts, beyond Fermi’s range.

“When you know you have a chance of observing this system only once every few years, you try to arrange for as much coverage as you can,” said Abdo, the principal investigator of the NASA-funded international campaign. “Understanding this system, where we know the nature of the compact object, may help us understand the nature of the compact objects in other, similar systems”.

While the EGRET telescope aboard NASA’s Compton Gamma-Ray Observatory had been observing this rare pair since the 1990s, no gamma-ray emission in the billion-electron-volt (GeV) energy range had ever been recorded. But, as the time of passage approached, the Large Area Telescope (LAT) aboard Fermi began to pick up faint gamma-ray emission. “During the first disk passage, which lasted from mid-November to mid-December, the LAT recorded faint yet detectable emission from the binary. We assumed that the second passage would be similar, but in mid-January 2011, as the pulsar began its second passage through the disk, we started seeing surprising flares that were many times stronger than those we saw before,” Abdo said.

To make this strange scenario even more unusual, radio and x-ray readings were nominal as the gamma-rays flared. “The most intense days of the flare were Jan. 20 and 21 and Feb. 2, 2011,” said Abdo. “What really surprised us is that on any of these days, the source was more than 15 times brighter than it was during the entire month-and-a-half-long first passage.”

It won’t happen again until May, 2014… But you can bet astronomers will be tuned in to catch the action!

Original Story Source: NASA / Fermi News.