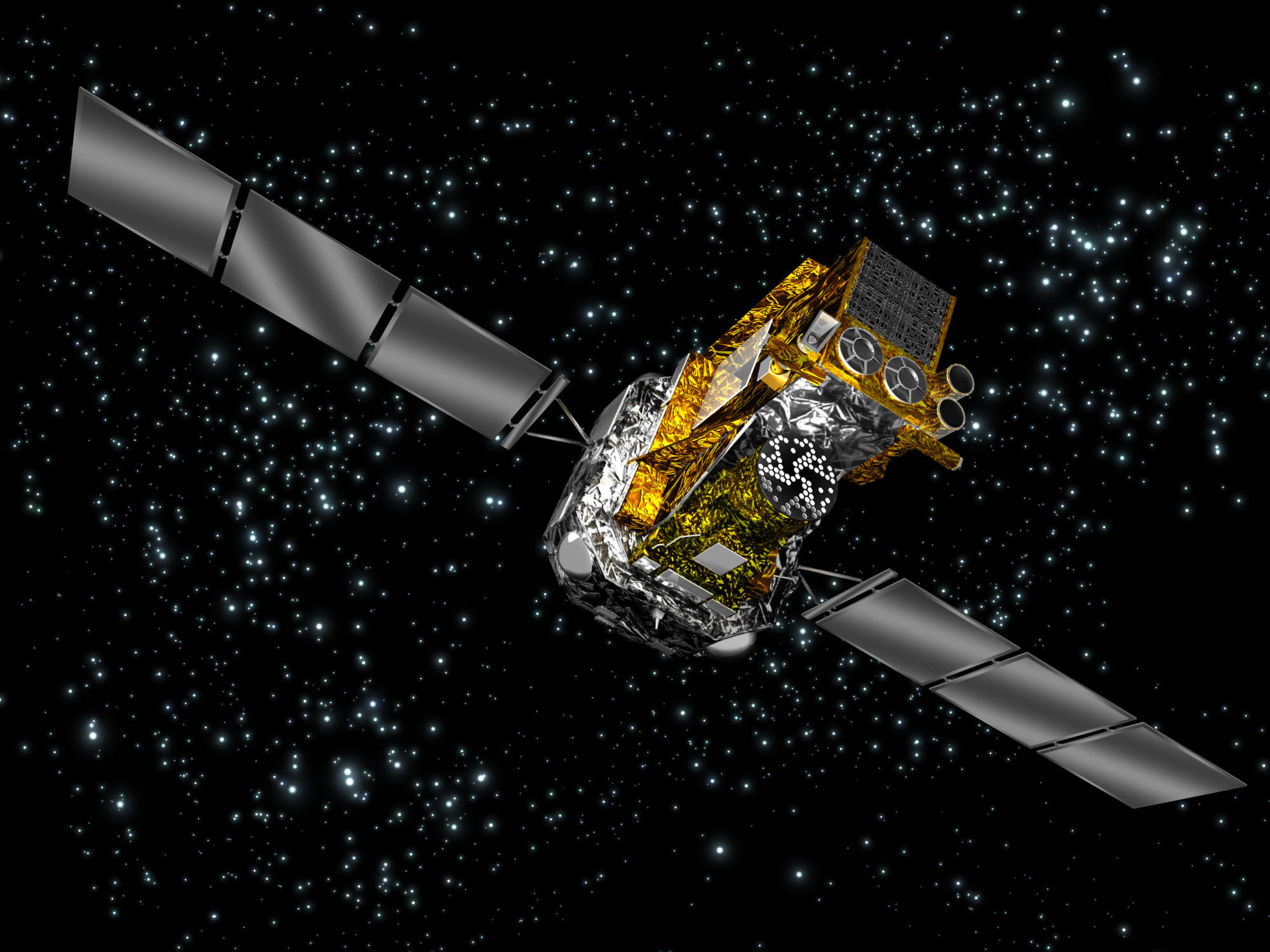

Caption: Artist’s impression of ESA’s orbiting gamma-ray observatory Integral. Image credit: ESA

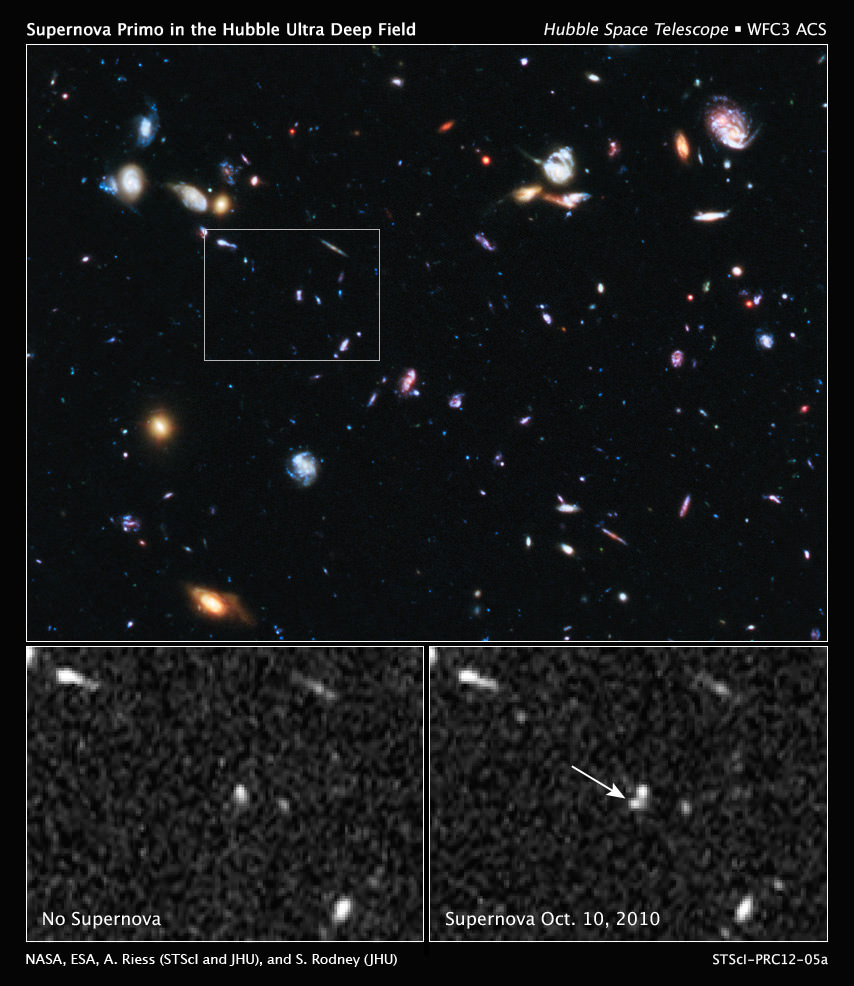

Integral, ESA’s International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory launched ten years ago this week. This is a good time to look back at some of the highlights of the mission’s first decade and forward to its future, to study at the details of the most sensitive, accurate, and advanced gamma-ray observatory ever launched. But the mission has also had some recent exciting research of a supernova remnant.

Integral is a truly international mission with the participation of all member states of ESA and United States, Russia, the Czech Republic, and Poland. It launched from Baikonur, Kazakhstan on October 17th 2002. It was the first space observatory to simultaneously observe objects in gamma rays, X-rays, and visible light. Gamma rays from space can only be detected above Earth’s atmosphere so Integral circles the Earth in a highly elliptical orbit once every three days, spending most of its time at an altitude over 60 000 kilometres – well outside the Earth’s radiation belts, to avoid interference from background radiation effects. It can detect radiation from events far away and from the processes that shape the Universe. Its principal targets are gamma-ray bursts, supernova explosions, and regions in the Universe thought to contain black holes.

5 metres high and more than 4 tonnes in weight Integral has two main parts. The service module is the lower part of the satellite which contains all spacecraft subsystems, required to support the mission: the satellite systems, including solar power generation, power conditioning and control, data handling, telecommunications and thermal, attitude and orbit control. The payload module is mounted on the service module and carries the scientific instruments. It weighs 2 tonnes, making it the heaviest ever placed in orbit by ESA, due to detectors’ large area needed to capture sparse and penetrating gamma rays and to shield the detectors from background radiation in order to make them sensitive. There are two main instruments detecting gamma rays. An imager producing some of the sharpest gamma-ray images and a spectrometer that gauges gamma-ray energies very precisely. Two other instruments, an X-ray monitor and an optical camera, help to identify the gamma-ray sources.

During its extended ten year mission Integral has has charted in extensive detail the central region of our Milky Way, the Galactic Bulge, rich in variable high-energy X-ray and gamma-ray sources. The spacecraft has mapped, for the first time, the entire sky at the specific energy produced by the annihilation of electrons with their positron anti-particles. According to the gamma-ray emission seen by Integral, some 15 million trillion trillion trillion pairs of electrons and positrons are being annihilated every second near the Galactic Centre, that is over six thousand times the luminosity of our Sun.

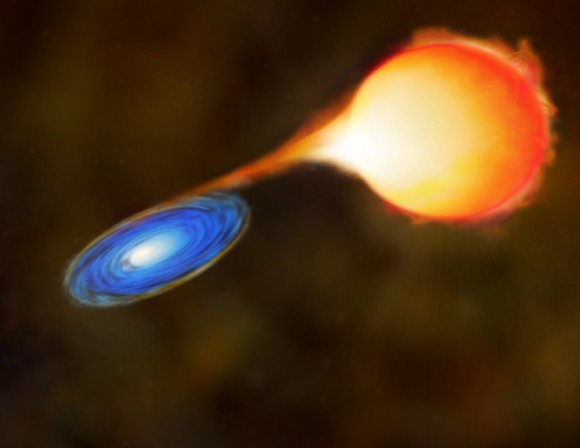

A black-hole binary, Cygnus X-1, is currently in the process of ripping a companion star to pieces and gorging on its gas. Studying this extremely hot matter just a millisecond before it plunges into the jaws of the black hole, Integral has discovered that some of it might be escaping along structured magnetic field lines. By studying the alignment of the waves of high-energy radiation originating from the Crab Nebula, Integral found that the radiation is strongly aligned with the rotation axis of the pulsar. This implies that a significant fraction of the particles generating the intense radiation must originate from an extremely organised structure very close to the pulsar, perhaps even directly from the powerful jets beaming out from the spinning stellar core.

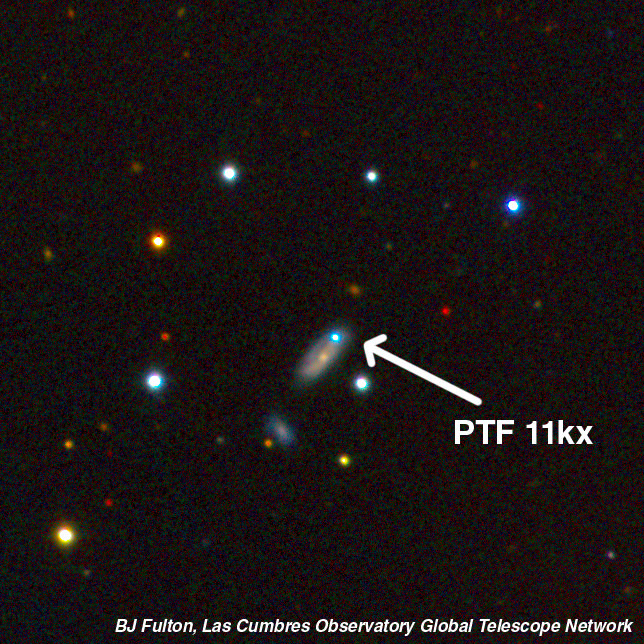

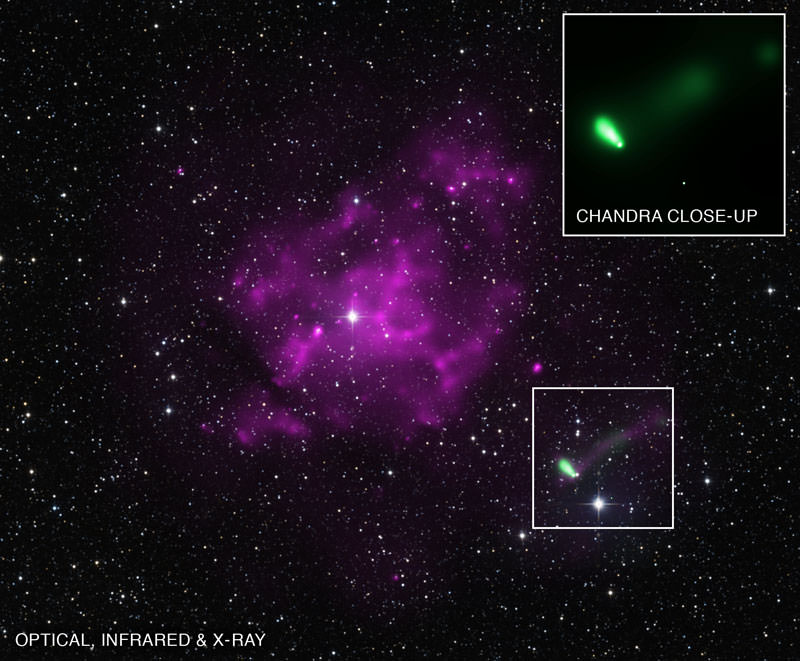

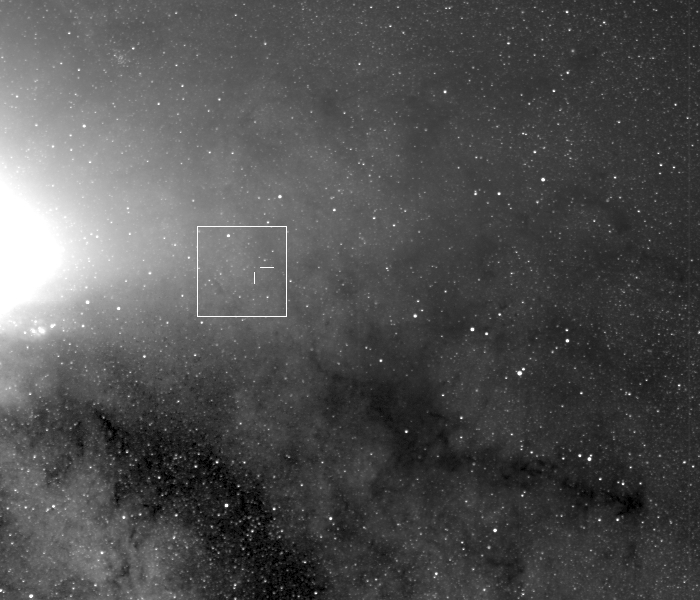

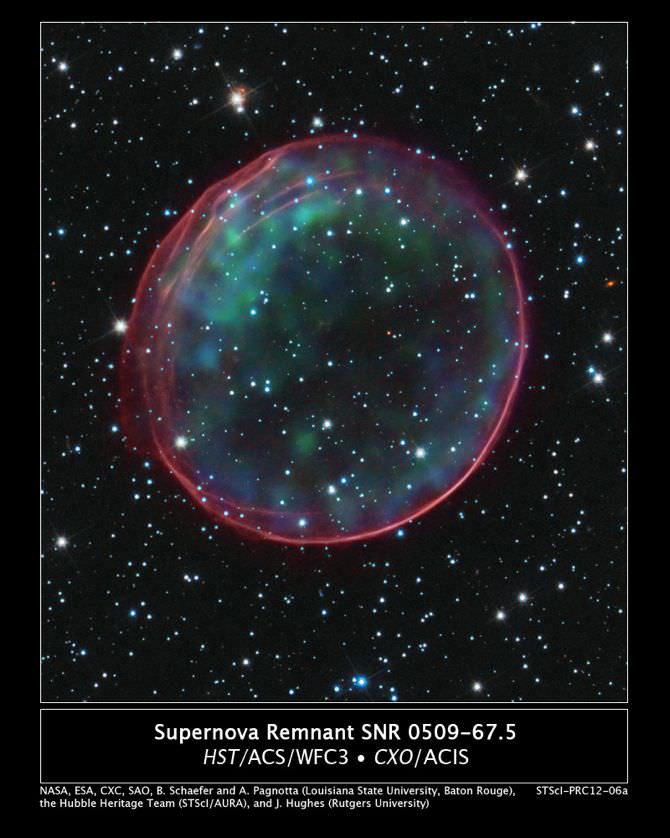

Just today ESA reported that Integral has made the first direct detection of radioactive titanium associated with supernova remnant 1987A. Supernova 1987A, located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, was close enough to be seen by the naked eye in February 1987, when its light first reached Earth. Supernovae can shine as brightly as entire galaxies for a brief time due to the enormous amount of energy released in the explosion, but after the initial flash has faded, the total luminosity comes from the natural decay of radioactive elements produced in the explosion. The radioactive decay might have been powering the glowing remnant around Supernova 1987A for the last 20 years.

During the peak of the explosion elements from oxygen to calcium were detected, which represent the outer layers of the ejecta. Soon after, signatures of the material from the inner layers could be seen in the radioactive decay of nickel-56 to cobalt-56, and its subsequent decay to iron-56. Now, after more than 1000 hours of observation by Integral, high-energy X-rays from radioactive titanium-44 in supernova remnant 1987A have been detected for the first time. It is estimated that the total mass of titanium-44 produced just after the core collapse of SN1987A’s progenitor star amounted to 0.03% of the mass of our own Sun. This is close to the upper limit of theoretical predictions and nearly twice the amount seen in supernova remnant Cas A, the only other remnant where titanium-44 has been detected. It is thought both Cas A and SN1987A may be exceptional cases

Christoph Winkler, ESA’s Integral Project Scientist says “Future science with Integral might include the characterisation of high-energy radiation from a supernova explosion within our Milky Way, an event that is long overdue.”

Find out more about Integral here

and about Integral’s study of Supernova 1987A here