According to modern cosmological models, the Universe began in a cataclysm event known as the Big Bang. This took place roughly 13.8 billion years ago, and was followed by a period of expansion and cooling. During that time, the first hydrogen atoms formed as protons and electrons combined and the fundamental forces of physics were born. Then, about 100 million years after the Big Bang, that the first stars and galaxies began to form.

The formation of the first stars was also what allowed for the creation of heavier elements, and therefore the formation of planets and all life as we know it. However, until now, how and when this process took place has been largely theoretical since astronomers did not know where the oldest stars in our galaxy were to be found. But thanks to a new study by a team of Spanish astronomers, we may have just found the oldest star in the Milky Way!

The study, titled “J0815+4729: A chemically primitive dwarf star in the Galactic Halo observed with Gran Telescopio Canarias“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Led by David S. Aguado of the Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias (IAC), the team included members from the University of La Laguna and the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC).

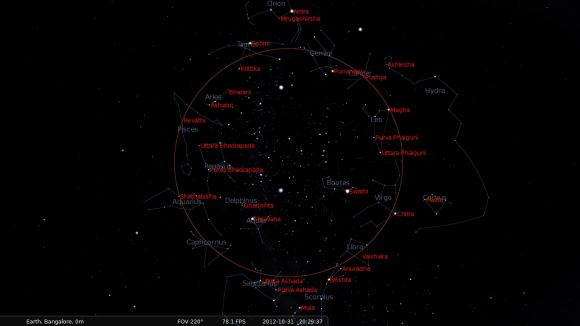

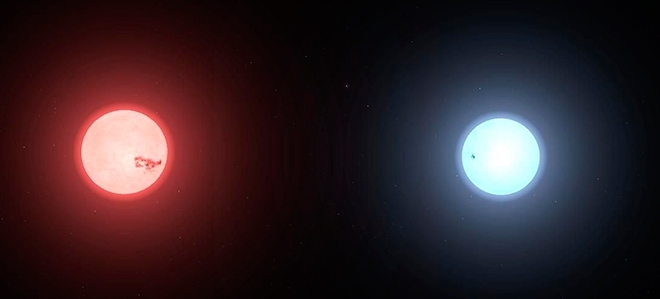

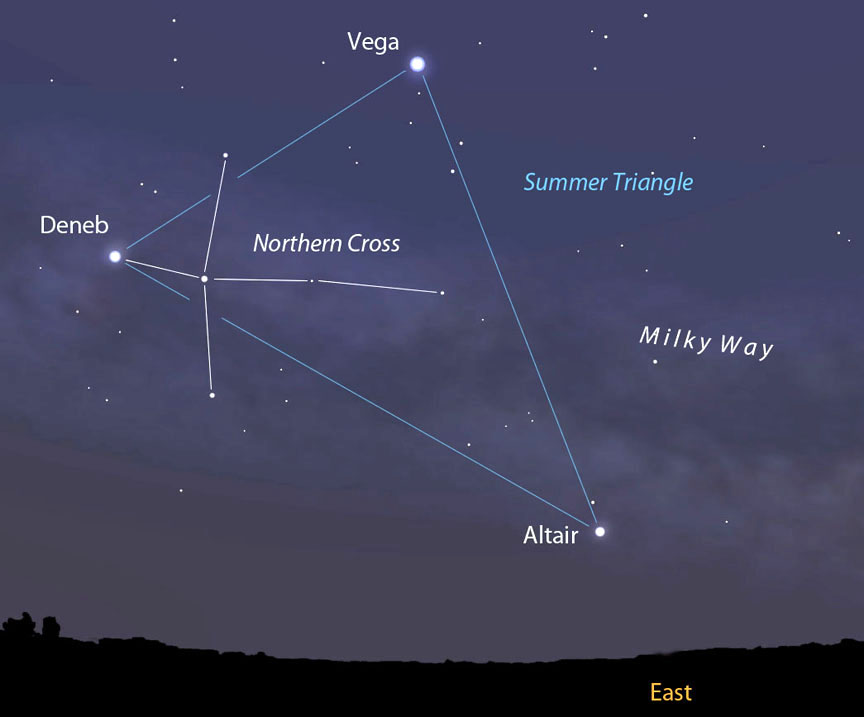

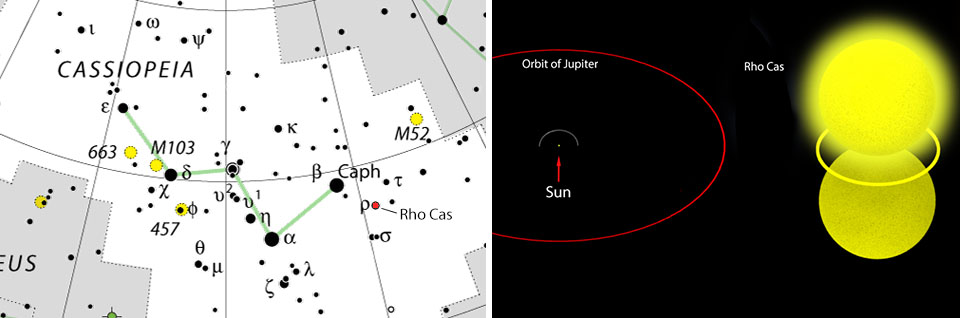

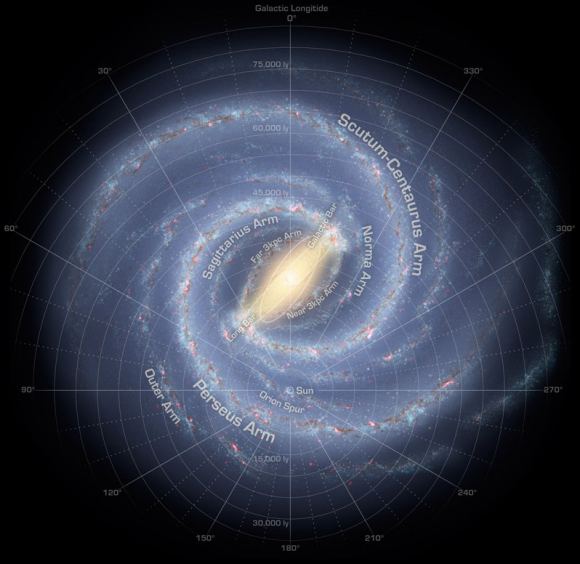

This star is located roughly 7,500 light years from the Sun, and was found in the halo of the Milky Way along the line of sight to the Lynx constellation. Known as J0815+4729, this star is still in its main sequence and has a low mass, (around 0.7 Solar Masses), though the research team estimates that it has a surface temperature that is about 400 degrees hotter – 6,215 K (5942 °C; 10,727 °F) compared to 5778 K (5505 °C; 9940 °F).

For the sake of their study, the team was looking for a star that showed signs of being metal-poor, which would indicate that it has been in its main sequence for a very long time. The team first selected J0815+4729 from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (SDSS-III/BOSS) and then conducted follow-up spectroscopic investigations to determine its composition (and hence its age).

This was done using the Intermediate dispersion Spectrograph and Imaging System (ISIS) at the William Herschel Telescope (WHT) and the Optical System for Imaging and low-intermediate-Resolution Integrated Spectroscopy (OSIRIS) at Gran Telescopio de Canarias (GTC), both of which are located at the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos on the island of La Palma.

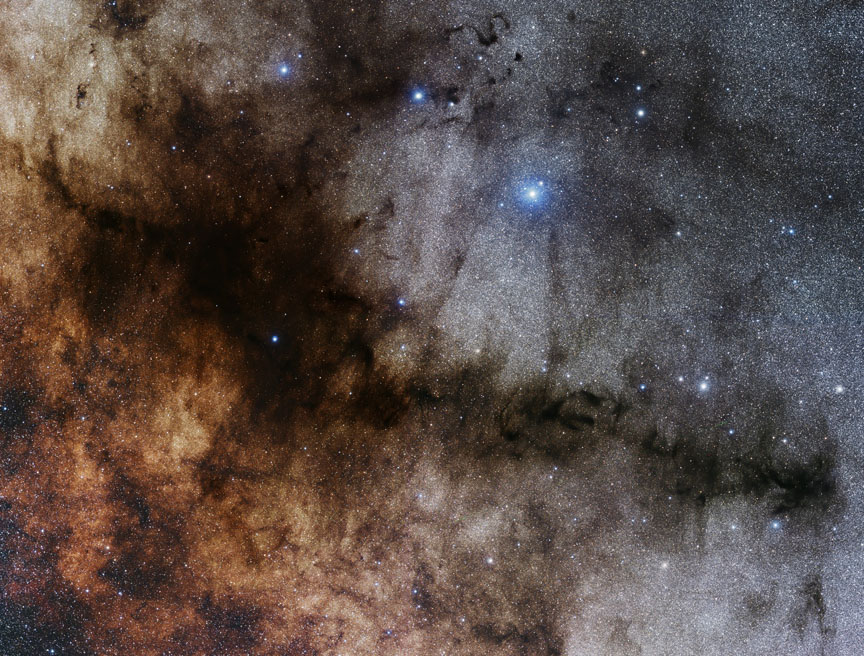

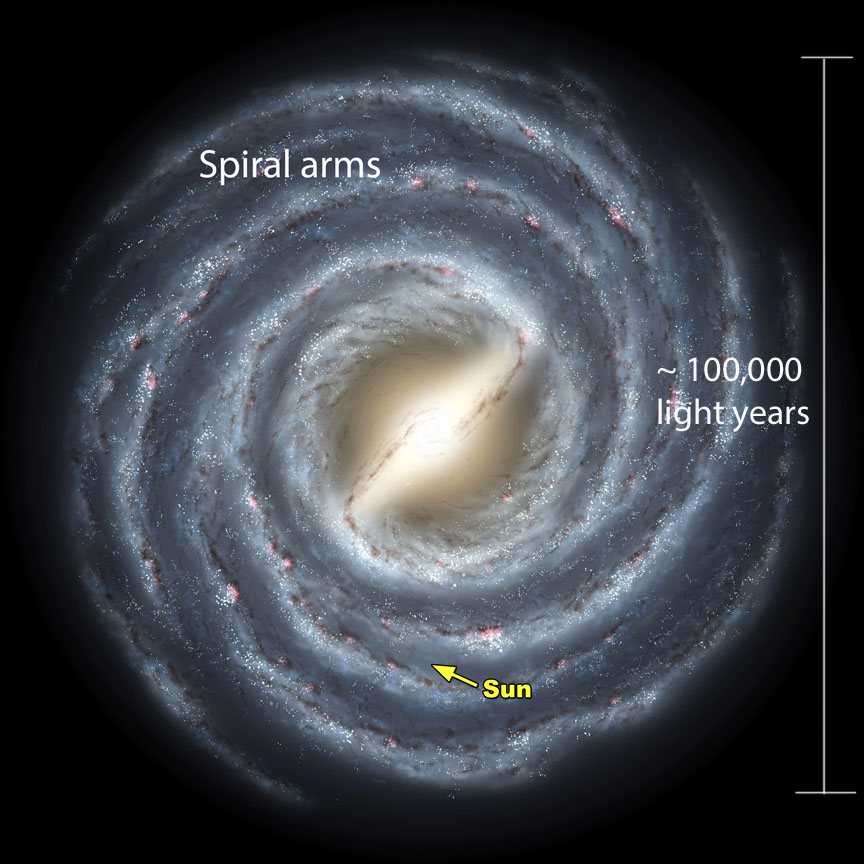

Consistent with what modern theory predicts, the star was found in the Galactic halo – the extended component of our galaxy that reaches beyond the galactic disk (the visible portion). It is in this region that the oldest and most metal-poor stars are believed to be found in galaxies, hence why the team was confident that a star dating back to the early Universe would be found here.

As Jonay González Hernández – a professor from the University of La Laguna, a member of the IAC and a co-author on the paper – explained in an IAC press release:

“Theory predicts that these stars could use material from the first supernovae, whose progenitors were the first massive stars in the galaxy, around 300 million years after the Big Bang. In spite of its age, and its distance away from us, we can still observe it.”

Spectra obtained by both the ISIS and OSIRIS instruments confirmed that the star was poor in metals, indicating that J0815+4729 has only one-millionth of the calcium and iron that the Sun contains. In addition, the team also noticed that the star has a higher carbon content than our Sun, accounting for almost 15% percent of its solar abundance (i.e. the relative abundance of its elements).

In short, J0815+4729 may be the most iron-poor and carbon-rich star currently known to astronomers. Moreover, finding it was rather difficult since the star is both weak in luminosity and was buried within a massive amount of SDSS/BOSS archival data. As Carlos Allende Prieto, another IAC researcher and a co-author on the paper, indicated:

“This star was tucked away in the database of the BOSS project, among a million stellar spectra which we have analysed, requiring a considerable observational and computational effort. It requires high-resolution spectroscopy on large telescopes to detect the chemical elements in the star, which can help us to understand the first supernovae and their progenitors.”

In the near future, the team predicts that next-generation spectrographs could allow for further research that would reveal more about the star’s chemical abundances. Such instruments include the HORS high-resolution spectrograph, which is presently in a trial phase on the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC).

“Detecting lithium gives us crucial information related to Big Bang nucleosynthesis,” said Rafael Rebolo, the director of the IAC and a coauthor of the paper. “We are working on a spectrograph of high-resolution and wide spectral range in order to measure the detailed chemical composition of stars with unique properties such as J0815+4719.”

Further Reading: IAC, The Astrophysical Journal Letters