[/caption]

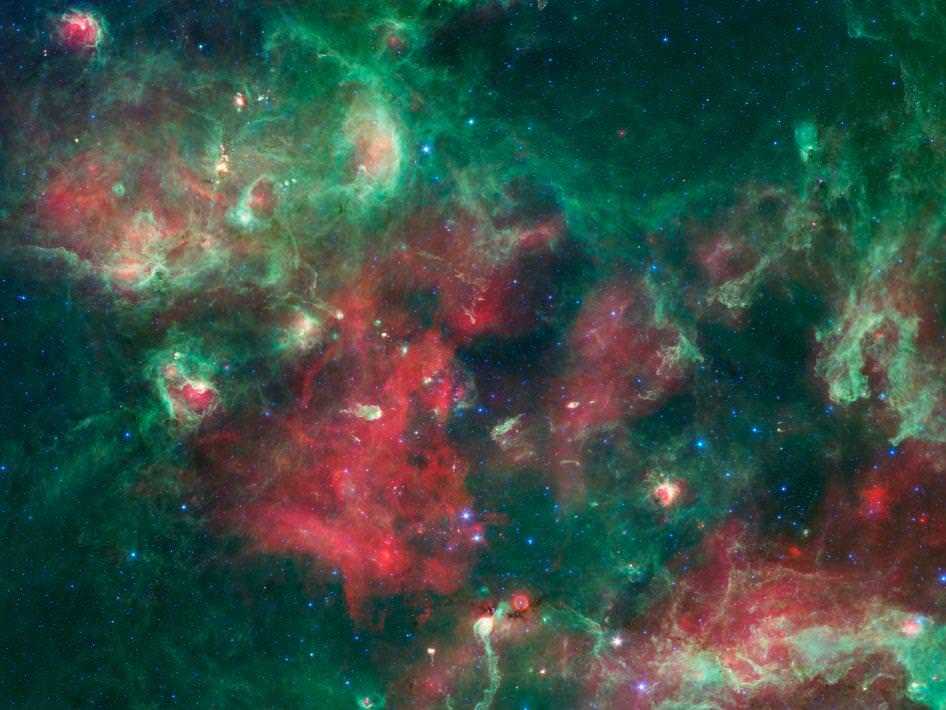

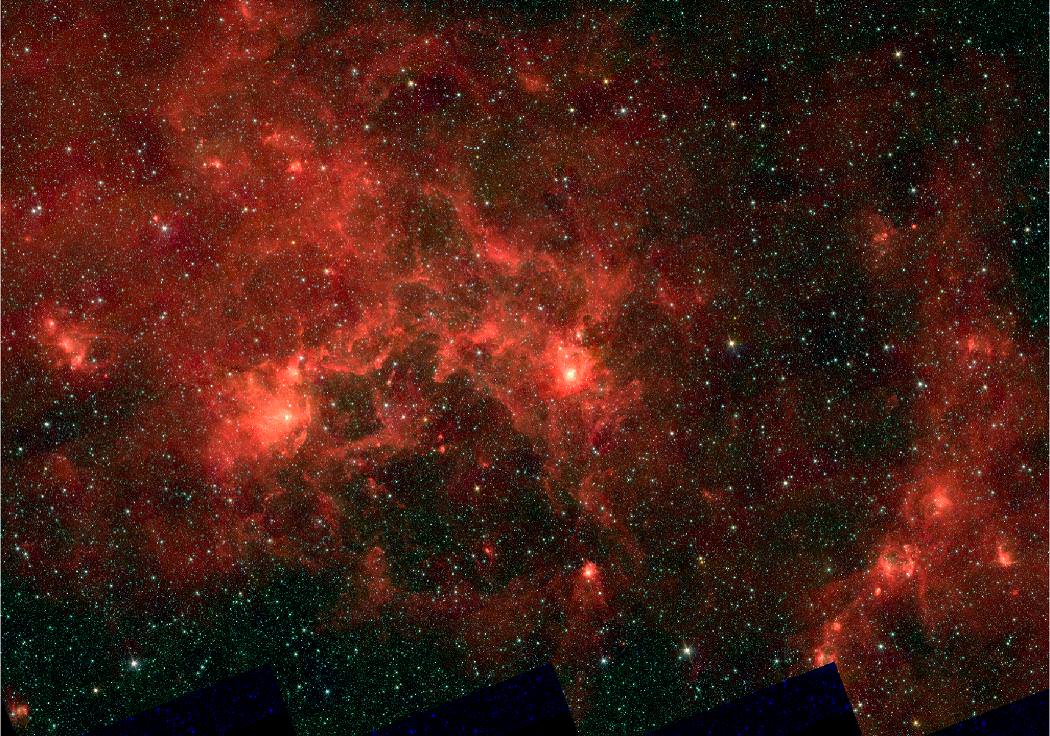

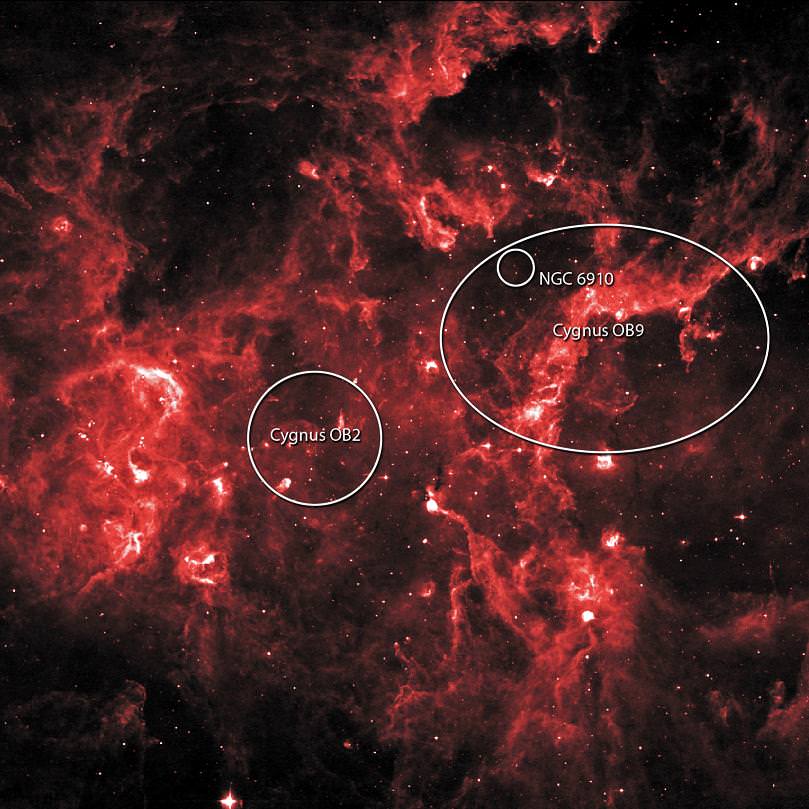

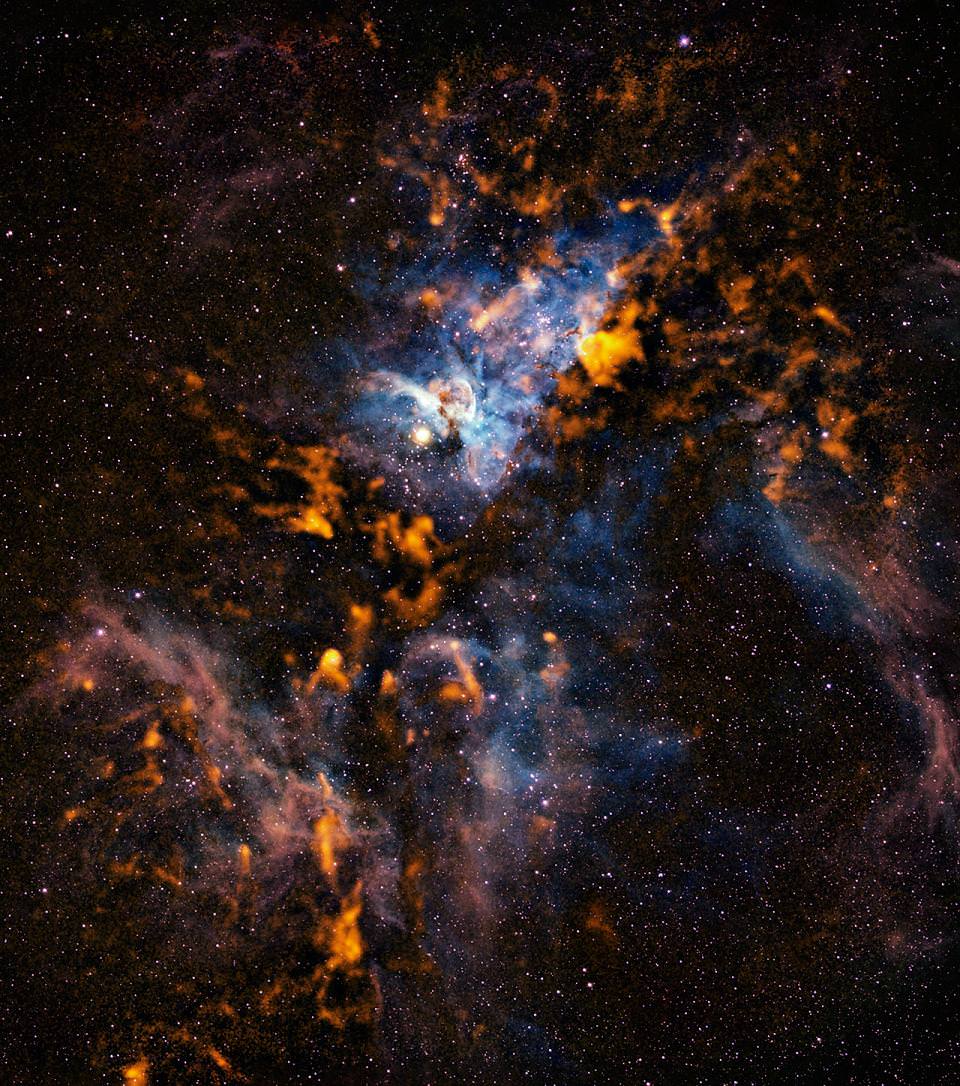

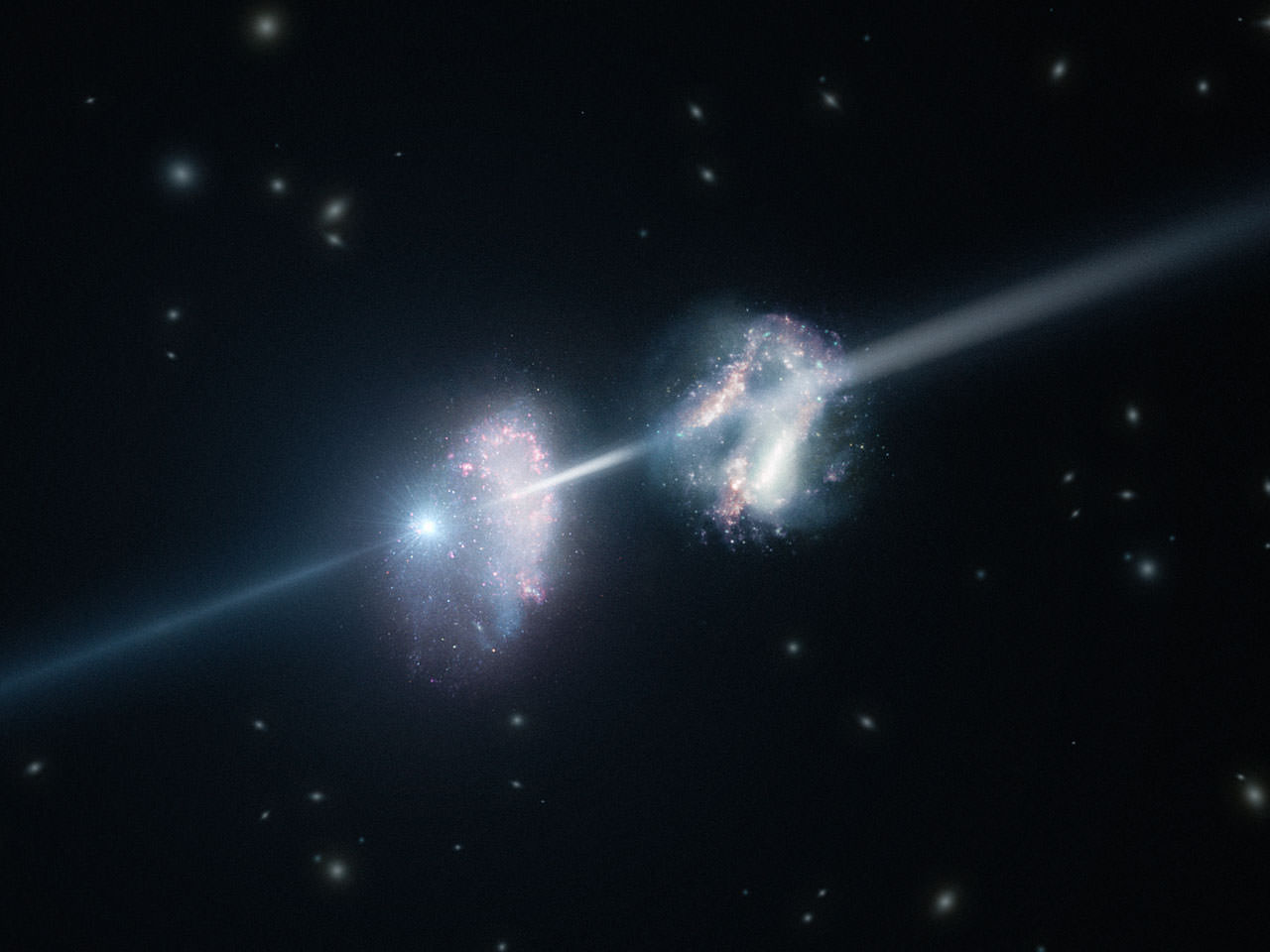

Thanks to the incredible infra-red imagery of NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, we’re able to take a look into a tortured region of star formation. Infrared light in this image has been color-coded according to wavelength. Light of 3.6 microns is blue, 4.5-micron light is blue-green, 8.0-micron light is green, and 24-micron light is red. The data was taken before the Spitzer mission ran out of its coolant in 2009, and began its “warm” mission. This image reveals one of the most active and tumultuous areas of the Milky Way – Cygnus X. Located some 4,500 light years away, the violent-appearing dust cloud holds thousands of massive stars and even more of moderate size. It is literally “star soup”…

“Spitzer captured the range of activities happening in this violent cloud of stellar birth,” said Joseph Hora of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., who presented the results today at the 219th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Austin, Texas. “We see bubbles carved out by massive stars, pillars of new stars, dark filaments lined with stellar embryos and more.”

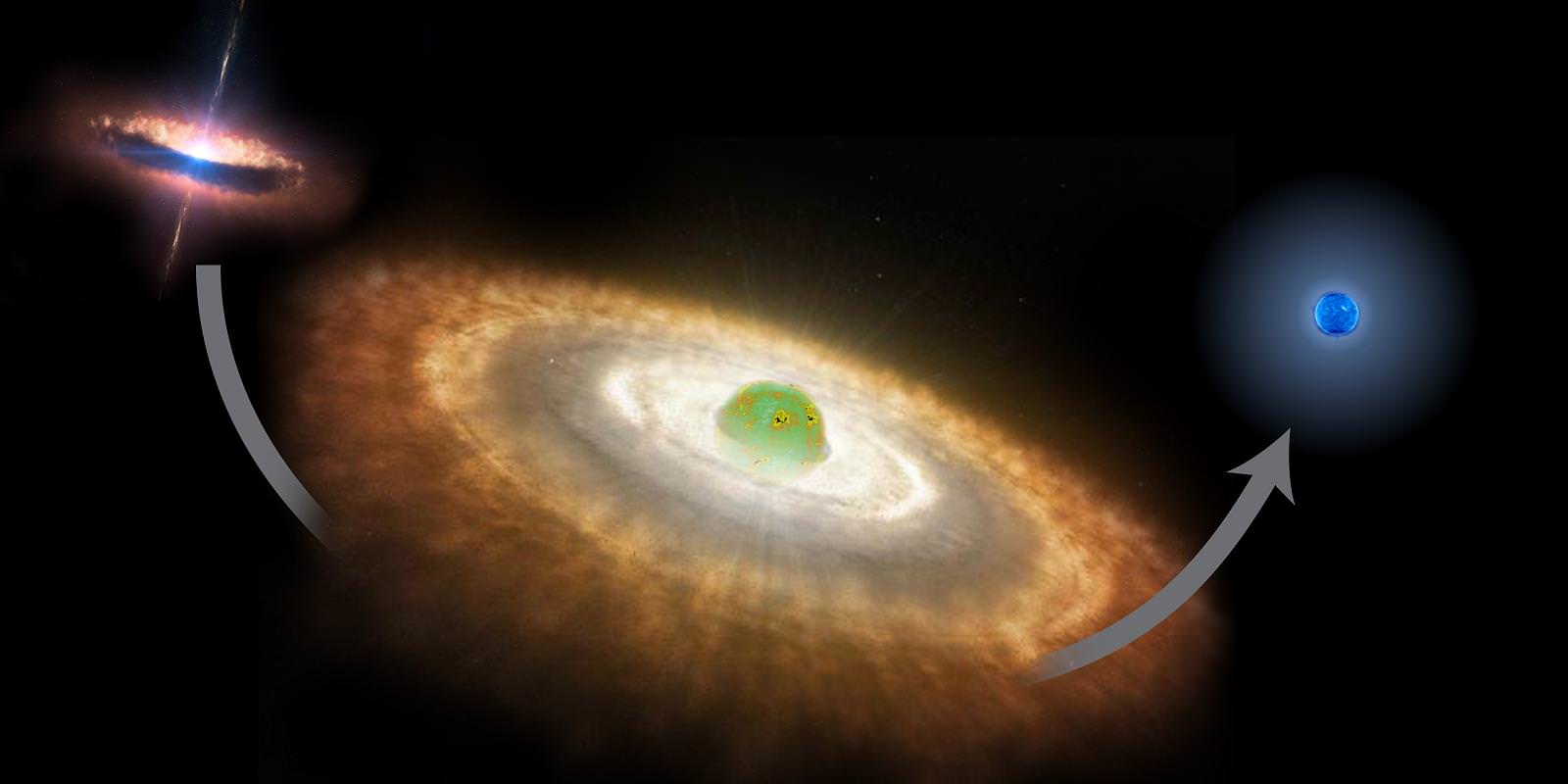

According to popular theory, stars are created in regions similar to Cygnus X. As their lives progress, they drift away from each other and it is surmised the Sun once belonged to a stellar association formed in a slightly less extreme environment. In regions like Cygnus X, the dust clouds are characterized with deformations caused by stellar winds and high radiation. The massive stars literally shred the clouds that birth them. This action can stop other stars from forming… and also cause the rise of others.

“One of the questions we want to answer is how such a violent process can lead to both the death and birth of new stars,” said Sean Carey, a team member from NASA’s Spitzer Science Center at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, Calif. “We still don’t know exactly how stars form in such disruptive environments.”

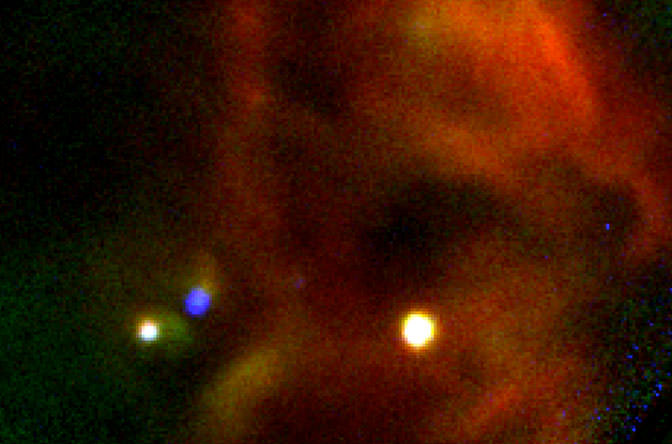

Thanks to Spitzer’s infra-red data, scientists are now able to paint a clearer picture of what happens in dusty complexes. It allows astronomers to peer behind the veil where embryonic stars were once hidden – and highlights areas like pillars where forming stars pop out inside their cavities. Another revelation is dark filaments of dust, where embedded stars make their home. It is visions like this that has scientists asking questions… Questions such as how filaments and pillars could be related.

“We have evidence that the massive stars are triggering the birth of new ones in the dark filaments, in addition to the pillars, but we still have more work to do,” said Hora.

Original Story Source: NASA Spitzer News Release.