The Sun is racing through the Galaxy at a speed that is 30 times greater than a space shuttle in orbit (clocking in at 220 km/s with respect to the galactic center). Most stars within the Milky Way travel at a relatively similar speed. But certain stars are definitely breaking the stellar speed limit. About one in a billion stars travel at a speed roughly 3 times greater than our Sun – so fast that they can easily escape the galaxy entirely!

We have discovered dozens of these so-called hypervelocity stars. But how exactly do these stars reach such high speeds? Astronomers from the University of Leicester may have found the answer.

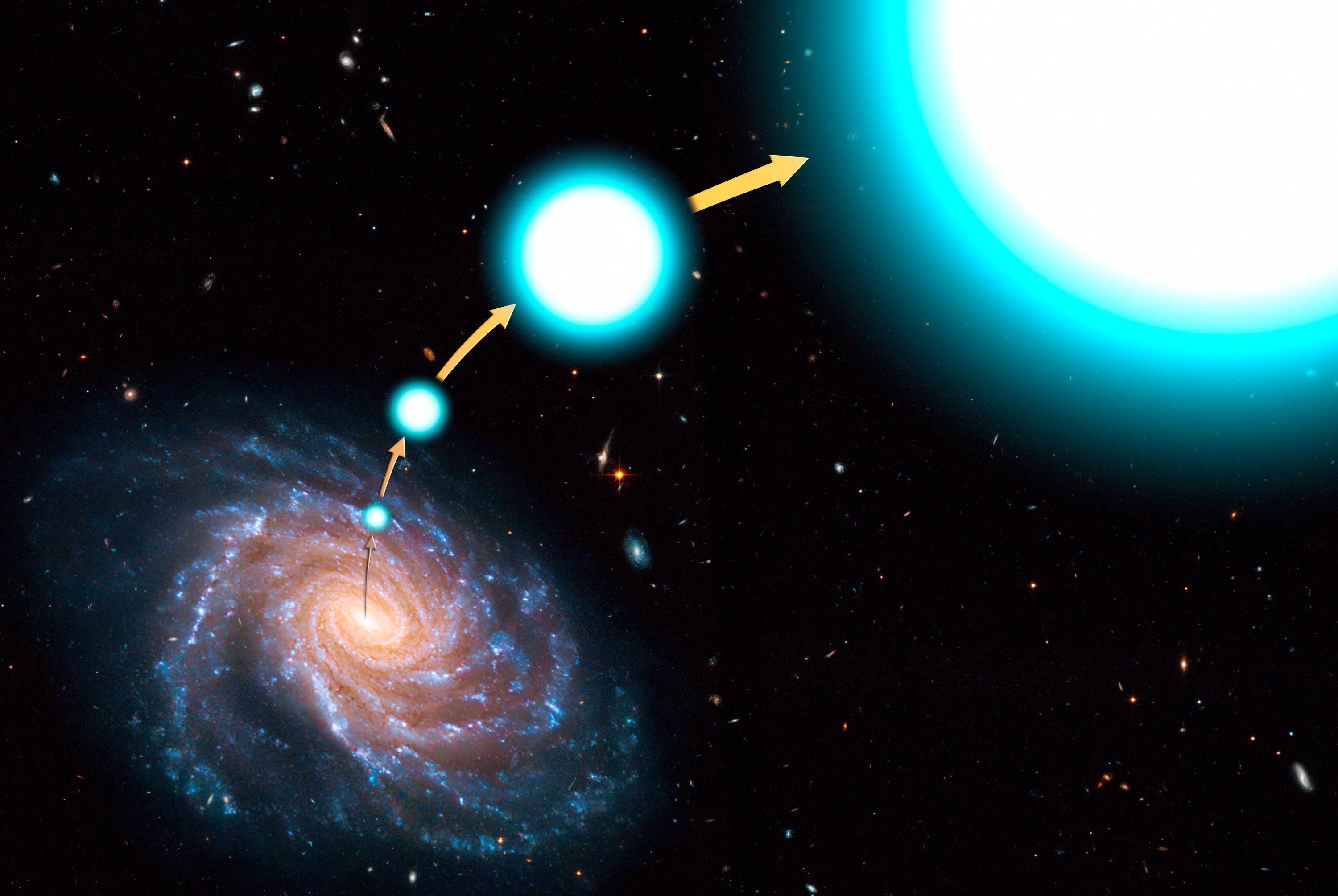

The first clue comes in observing hypervelocity stars, where we can note their speed and direction. From these two measurements, we can trace these stars backward in order to find their origin. Results show that most hypervelocity stars begin moving quickly in the Galactic Center.

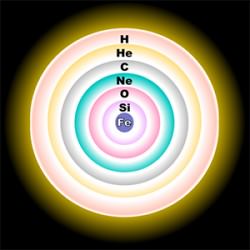

We now have a rough idea of where these stars gain their speed, but not how they reach such high velocities. Astronomers think two processes are likely to kick stars to such great speeds. The first process involves an interaction with the supermassive black hole (Sgr A*) at the center of our Galaxy. When a binary star system wanders too close to Sgr A*, one star is likely to be captured, while the other star is likely to be flung away from the black hole at an alarming rate.

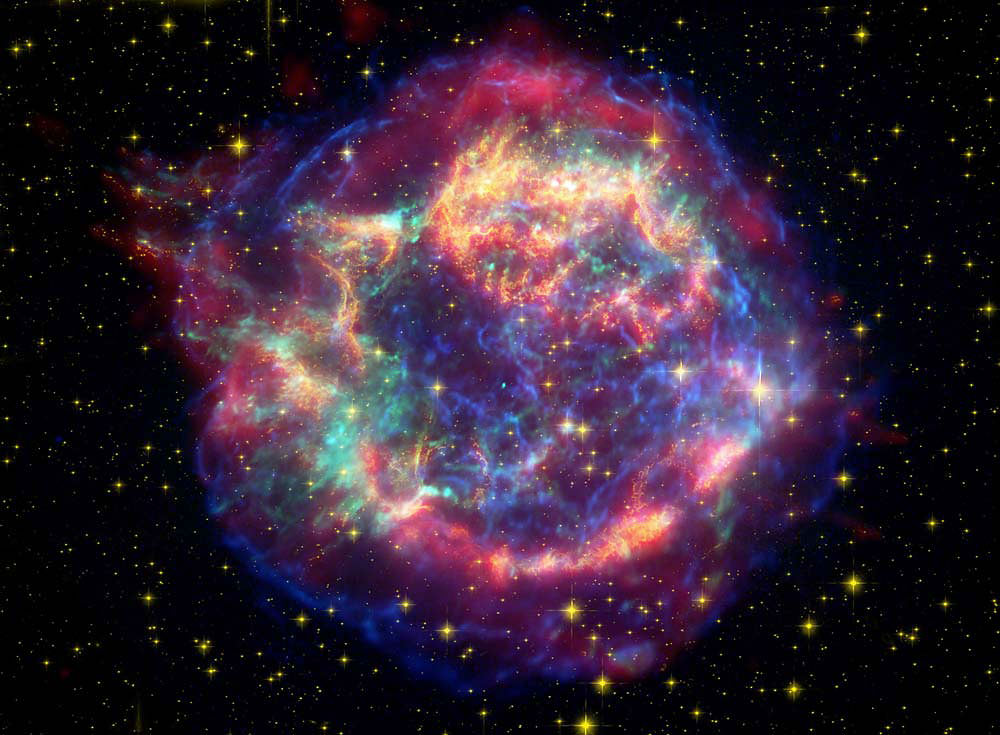

The second process involves a supernova explosion in a binary system. Dr. Kastytis Zubovas, lead author on the paper summarized here, told Universe Today, “Supernova explosions in binary systems disrupt those systems and allow the remaining star to fly away, sometimes with enough velocity to escape the Galaxy.”

There is, however, one caveat. Binary stars in the center of our Galaxy will both be orbiting each other and orbiting Sgr A*. They will have two velocities associated with them. “If the velocity of the star around the binary’s center of mass happens to line up closely with the velocity of the center of mass around the supermassive black hole, the combined velocity may be large enough to escape the Galaxy altogether,” explained Zubovas.

In this case, we can’t sit around and wait to observe a supernova explosion breaking up a binary system. We would have to be very lucky to catch that! Instead, astronomers rely on computer modeling to recreate the physics of such an event. They set up multiple calculations in order to determine the statistical probability that the event will occur, and check if the results match observations.

Astronomers from the University of Leicester did just this. Their model includes multiple input parameters, such as the number of binaries, their initial locations, and their orbital parameters. It then calculates when a star might undergo a supernova explosion, and depending on the position of the two stars at that time, the final velocity of the remaining star.

The probability that a supernova disrupts a binary system is greater than 93%. But does the secondary star then escape from the galactic center? Yes, 4 – 25% of the time. Zubovas described, “Even though this is a very rare occurrence, we may expect several tens of such stars to be created over 100 million years.” The final results suggest that this model ejects stars with rates high enough to match the observed number of hypervelocity stars.

Not only do the number of hypervelocity stars match observations but also their distribution throughout space. “Hypervelocity stars produced by our supernova disruption method are not evenly distributed on the sky,” said Dr. Graham Wynn, a co-author on the paper. “They follow a pattern which retains an imprint of the stellar disk they formed in. Observed hypervelocity stars are seen to follow a pattern much like this.”

In the end, the model was very successful at describing the observed properties of hypervelocity stars. Future research will include a more detailed model that will allow astronomers to understand the ultimate fate of hypervelocity stars, the effect that supernova explosions have on their surroundings, and the galactic center itself.

It’s likely that both scenarios – binary systems interacting with the supermassive black hole and one undergoing a supernova explosion – form hypervelocity stars. Studying both will continue to answer questions about how these speedy stars form.

The results will be published in the Astrophysical Journal (preprint available here)