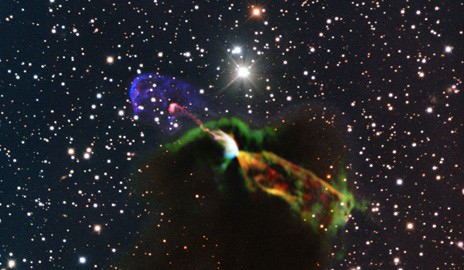

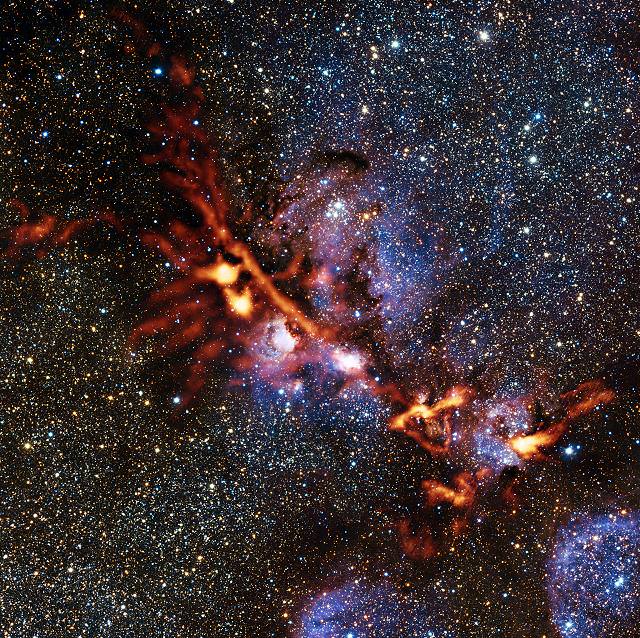

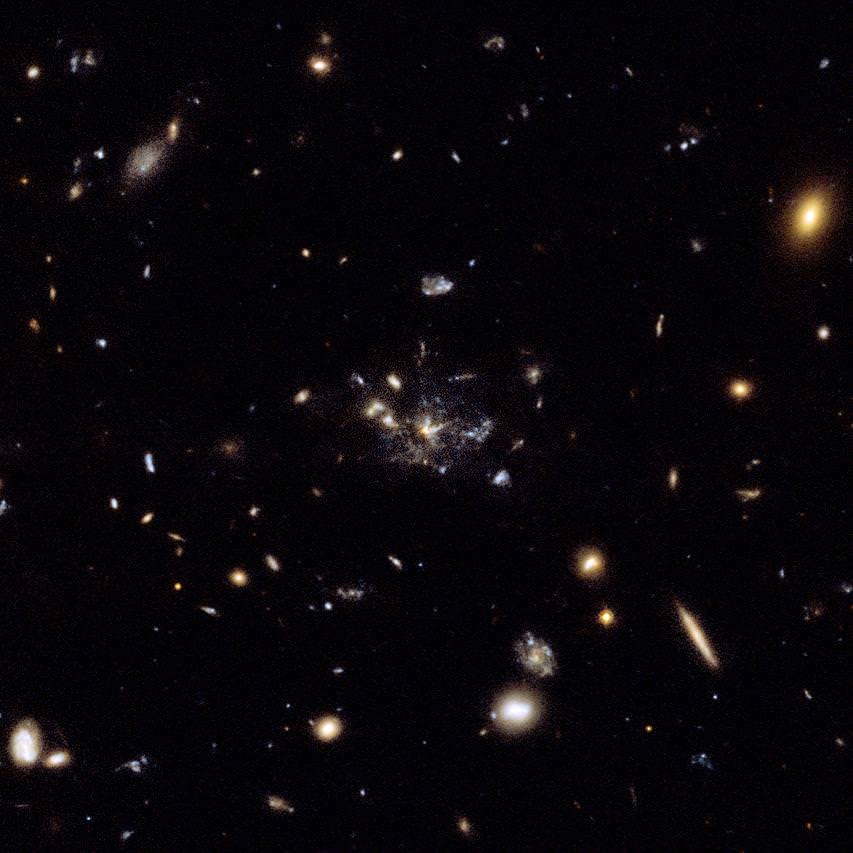

Some 160,000 light years away towards the constellation of Dorado (the Swordfish), is an amazing area of starbirth and death. Located in our celestial neighbor, the Large Magellanic Cloud, this huge stellar forge sculpts vast clouds of gas and dust into hot, new stars and carves out ribbons and curls of nebulae. However, in this image taken by ESO’s Very Large Telescope, there’s more. Stellar annihilation also awaits and shows itself as bright fibers left over from a supernova event.

For southern hemisphere observers, one of our nearest galactic neighbors, the Large Magellanic Cloud, is a well-known sight and holds many cosmic wonders. While the image highlights just a very small region, try to grasp the sheer size of what you are looking at. The fiery forge you see is several hundred light years across, and the factory in which it is contained spans 14,000 light years. Enormous? Yes. But compared to the Milky Way, it’s ten times smaller.

Even at such a great distance, the human eye can see many bright regions where new stars are actively forming, such as the Tarantula Nebula. This new image, taken by ESO’s Very Large Telescope at the Paranal Observatory in Chile, explores an area cataloged as NGC 2035 (right), sometimes nicknamed the Dragon’s Head Nebula. But, just what are we looking at?

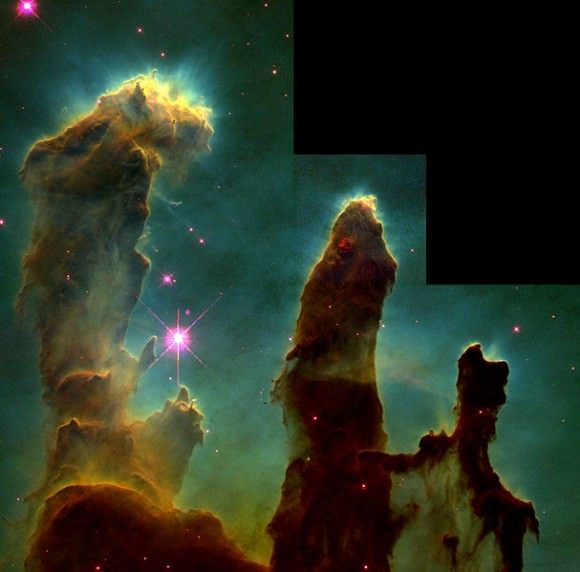

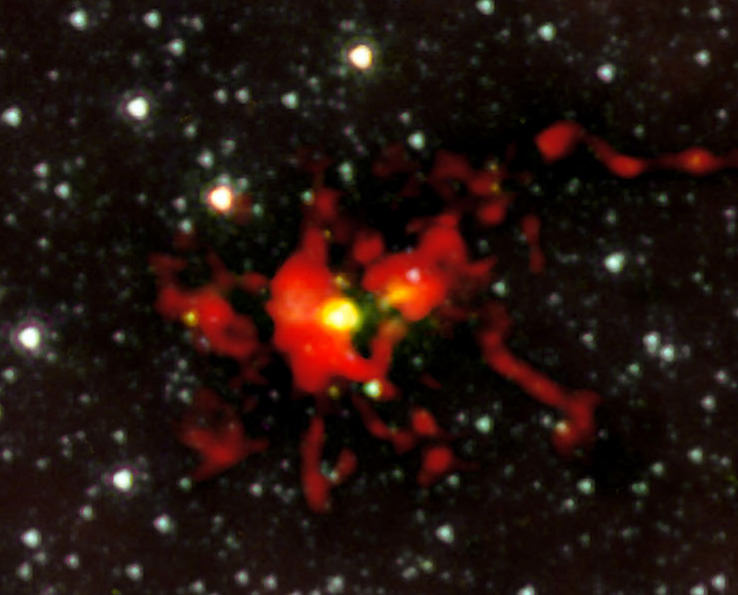

The Dragon’s Head is an HII region, more commonly referred to as an emission nebula. Here, young stars pour forth energetic radiation and illuminate the surrounding clouds. The radiation tears electrons away from the atoms contained within the gas. These atoms then gel again with other atoms and release light. Swirling in the mix is dark dust, which absorbs the light and creates deep shadows and create contrast in the nebula’s structure.

However, as we look deep into this image, there’s even more… a fiery finale. At the left of the photo you’ll see the results of one of the most violent events in the Universe – a supernova explosion. These troubled tendrils are all that’s left of what once was a star and its name is SNR 0536-67.6. Perhaps when it exploded, it was so bright that it was capable of outshining the Magellanic Cloud… fading away over the weeks or months that followed. However, it left a lasting impression!

Original Story Source: ESO Image Release.