[/caption]

“Life as we know it” seems to be the common caveat in our search for other living things in the Universe. But there’s also the possibility of life “as we don’t know it.” A new study from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope hints that planets around stars cooler than our sun might possess a different mix of potentially life-forming, or “prebiotic,” chemicals. While life on Earth is thought to have arisen from a hot soup of different chemicals, would the same life-generating mix come together around other stars with different temperatures? (And should we call it ‘The Gazpacho Effect?’) “Prebiotic chemistry may unfold differently on planets around cool stars,” said Ilaria Pascucci, lead author of the new study.

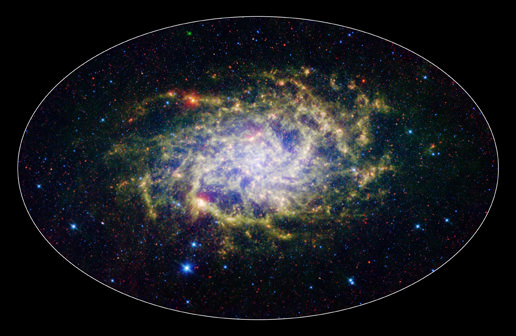

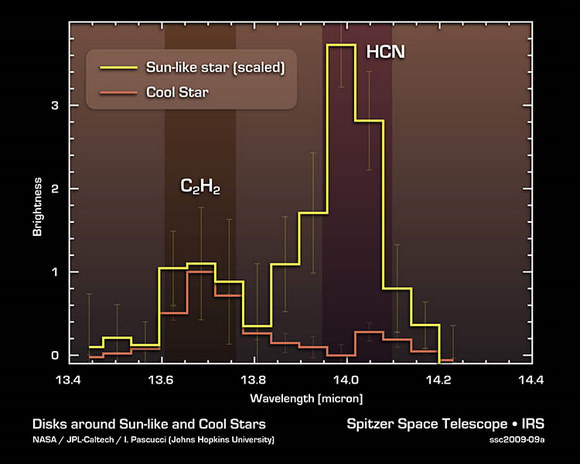

Pascussi and her team used Spitzer to examine the planet-forming disks around 17 cool and 44 sun-like stars. The stars are all about one to three million years old, an age when planets are thought to be forming. The astronomers specifically looked for ratios of hydrogen cyanide to a baseline molecule, acetylene. Using Spitzer’s infrared spectrograph, an instrument that breaks light apart to reveal the signatures of chemicals, the researchers looked for a prebiotic chemical, called hydrogen cyanide, in the planet-forming material swirling around the stars. Hydrogen cyanide is a component of adenine, which is a basic element of DNA. DNA can be found in every living organism on Earth.

The researchers detected hydrogen cyanide molecules in disks circling 30 percent of the yellow stars like our sun — but found none around cooler and smaller stars, such as the reddish-colored “M-dwarfs” and “brown dwarfs” common throughout the universe.

The team did detect their baseline molecule, acetylene, around the cool stars, demonstrating that the experiment worked. This is the first time that any kind of molecule has been spotted in the disks around cool stars.

“Perhaps ultraviolet light, which is much stronger around the sun-like stars, may drive a higher production of the hydrogen cyanide,” said Pascucci.

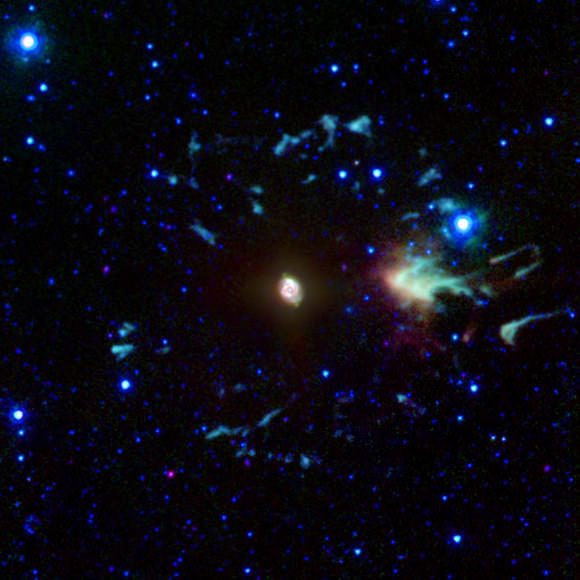

Young stars are born inside cocoons of dust and gas, which eventually flatten to disks. Dust and gas in the disks provide the raw material from which planets form. Scientists think the molecules making up the primordial ooze of life on Earth might have formed in such a disk. Prebiotic molecules, such as adenine, are thought to have rained down to our young planet via meteorites that crashed on the surface.

“It is plausible that life on Earth was kick-started by a rich supply of molecules delivered from space,” said Pascucci.

The findings have implications for planets that have recently been discovered around M-dwarf stars. Some of these planets are thought to be large versions of Earth, the so-called super Earths, but so far none of them are believed to orbit in the habitable zone, where water would be liquid. If such a planet is discovered, could it sustain life?

Astronomers aren’t sure. M-dwarfs have extreme magnetic outbursts that could be disruptive to developing life. But, with the new Spitzer results, they have another piece of data to consider: these planets might be deficient in hydrogen cyanide, a molecule thought to have eventually become a part of us.

Said Douglas Hudgins, the Spitzer program scientist at NASA Headquarters, Washington, “Although scientists have long been aware that the tumultuous nature of many cool stars might present a significant challenge for the development of life, this result begs an even more fundamental question: Do cool star systems even contain the necessary ingredients for the formation of life? If the answer is no then questions about life around cool stars become moot.”

Or, could life form differently around cooler stars from anything we know?

Source: JPL