The Blood Moon cometh.

One of the top astronomy events of 2018 occurs on the evening of Friday, July 27th, when the Moon enters the shadow of the Earth for a total lunar eclipse. In the vernacular that is the modern internet, this is what’s becoming popularly known as a “Blood Moon,” a time when the Moon reddens due to the refracted sunlight from a thousand sunsets falling upon it. Standing on the surface of the Moon during a total lunar eclipse (which no human has yet to do) you would see a red “ring of fire” ’round the limb of the eclipsed Earth.

This is the second total lunar eclipse for 2018, and the middle of a unique eclipse season bracketed by two partial solar eclipses, one on July 13th, and another crossing the Arctic and Scandinavia on August 11th.

The July 27th total lunar eclipse technically begins around 17:15 Universal Time (UT), when the Moon enters the bright penumbral edge of the Earth’s shadow. Expect the see a slight shading on the southwest edge of the Moon’s limb about 30 minutes later. The real action begins around 18:24 UT, when the Moon starts to enter the dark inner umbra and the partial phases of the eclipse begin. Totality runs from 19:30 UT to 21:13 UT, and the cycle reverses through partial and penumbral phases, until the eclipse ends at 23:29 UT.

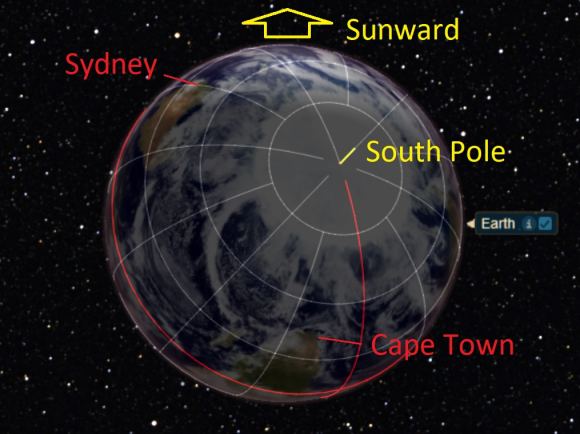

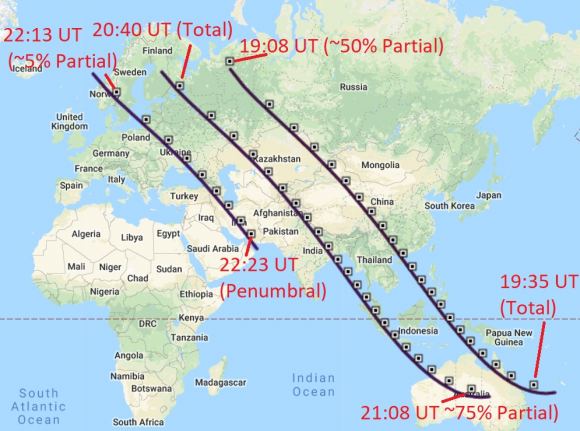

Centered over the Indian Ocean region, Africa, Europe and western Asia get a good front row seat to the entire total lunar eclipse. Australia and eastern Asia see the eclipse in progress at moonset, and South America sees the eclipse in progress at moonrise just after sunset. Only North America sits this one out.

Now, this total lunar eclipse is special for a few reasons.

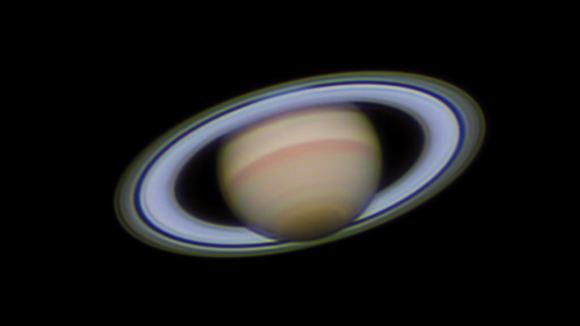

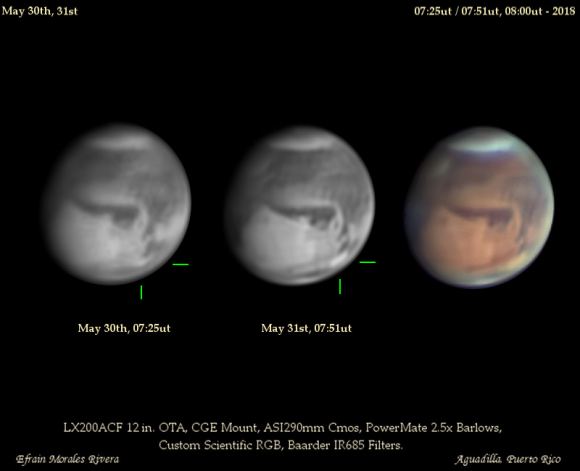

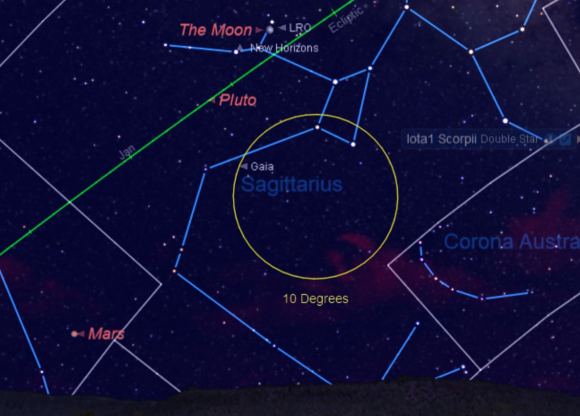

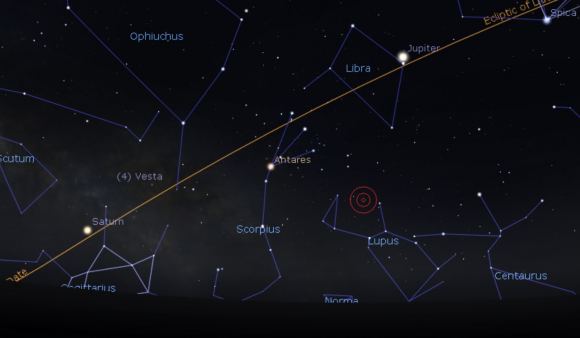

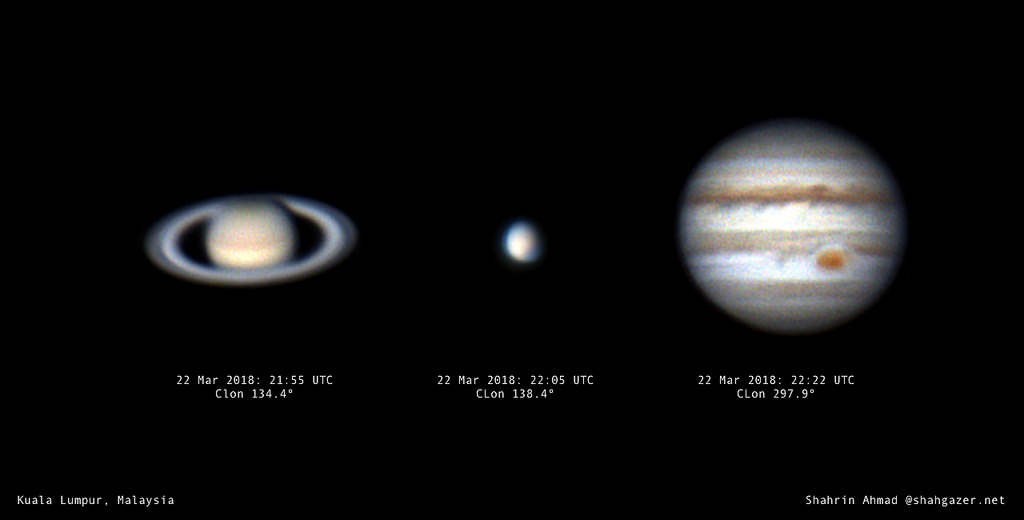

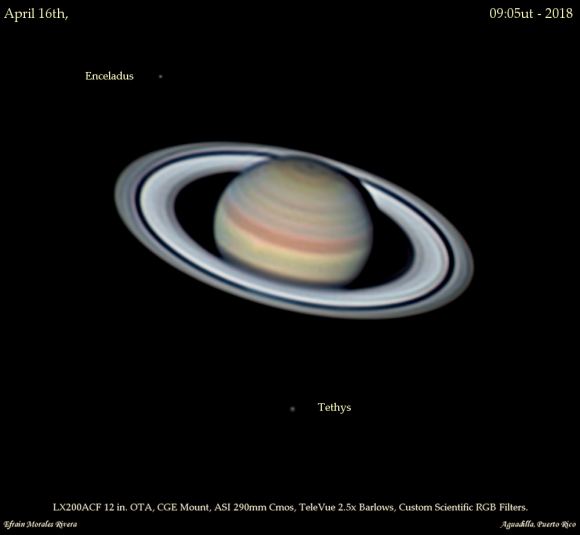

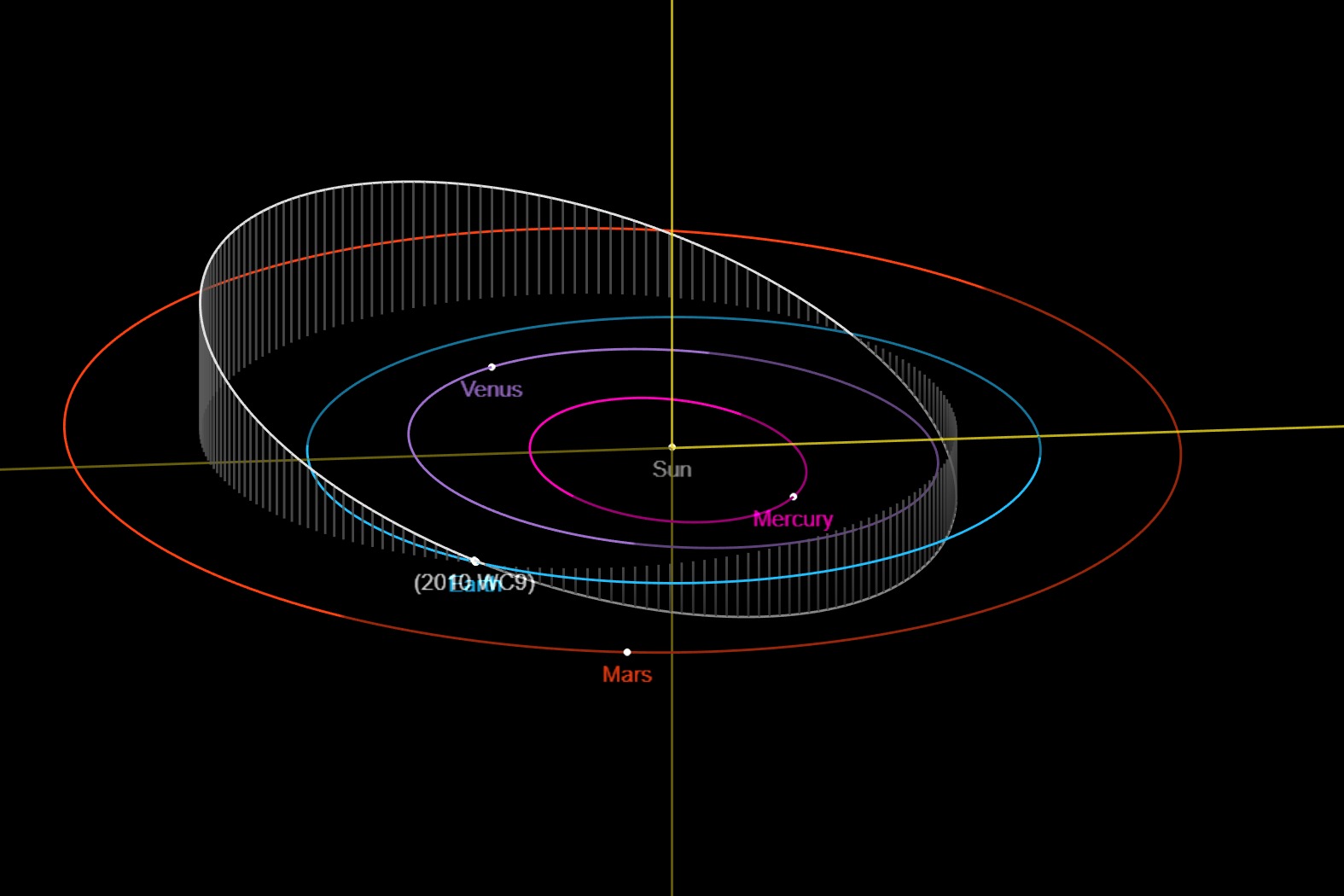

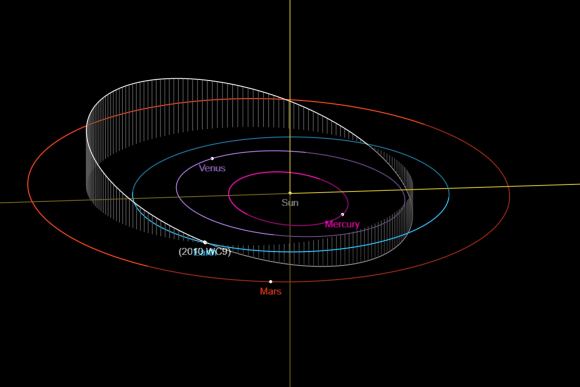

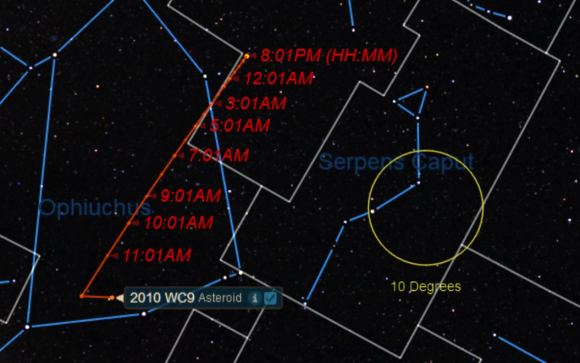

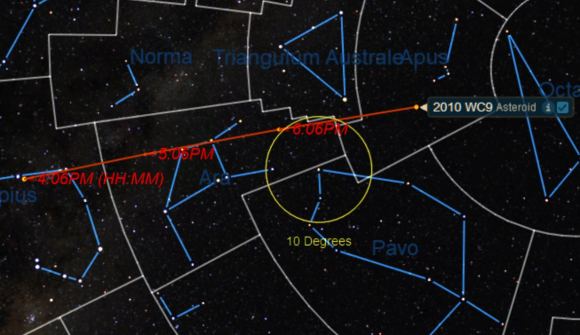

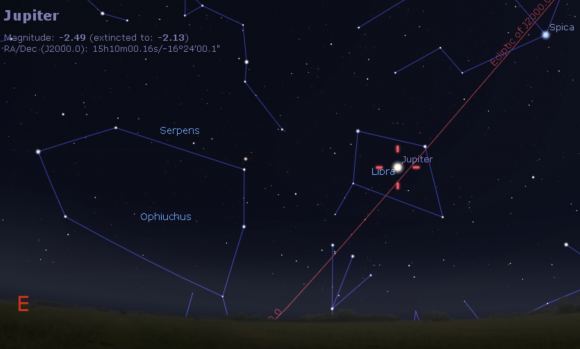

First off, we’ll have the planet Mars at opposition less than 15 hours prior to the eclipse. This means the Red Planet will shine at a brilliant magnitude -2.8, just eight degrees from the crimson Moon during the eclipse, a true treat and an easy crop to get both in frame. We fully expect to see some great images of Mars at opposition along with the eclipsed Moon.

How close can the two get? Well, stick around until April 27th, 2078 and you can see the Moon occult (pass in front of) Mars during a penumbral lunar eclipse as seen from South America.

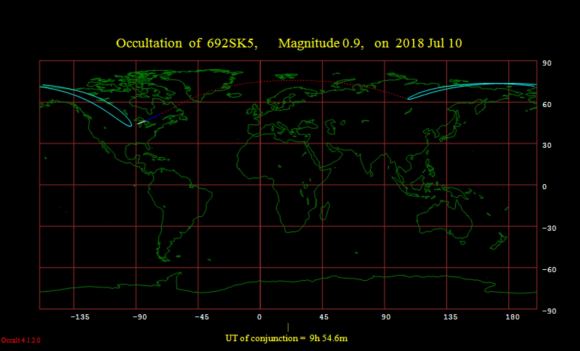

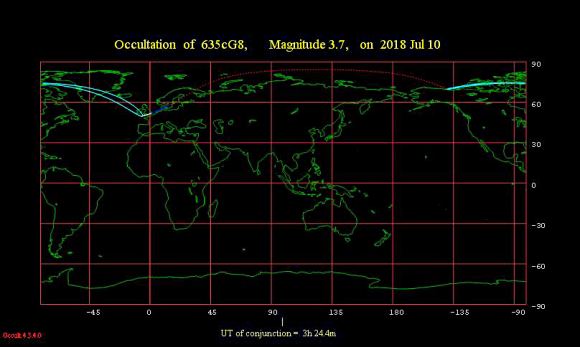

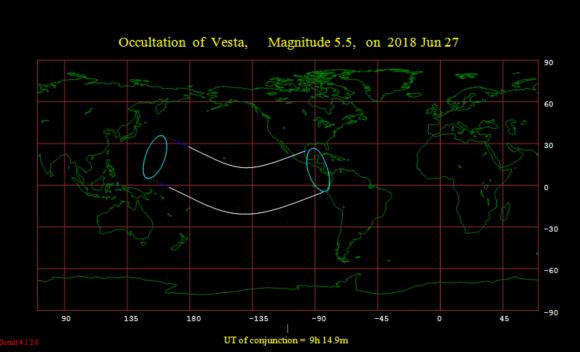

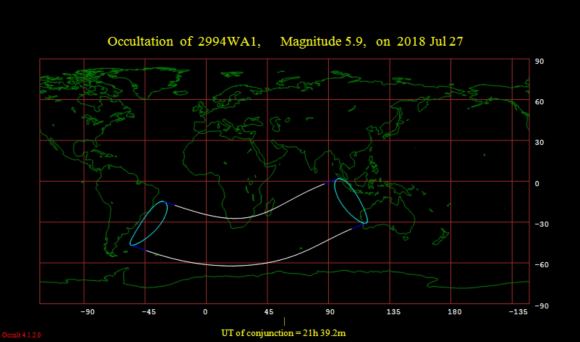

And speaking of occultations, the Moon occults some interesting stars during totality Friday, the brightest of which is the +5.9 magnitude double star Omicron Capricorni (SAO 163626) as seen from Madagascar and the southern tip of Africa. Omicron Capricorni has a wide separation of 22″.

The second unique fact surrounding this eclipse is one you’ve most likely already heard: it is indeed the longest one for this century… barely. This occurs because the Moon reaches its descending node along the ecliptic on July 27th at 22:40 UT, just 21 minutes after leaving the umbral shadow of the Earth. This makes for a very central eclipse, nearly piercing the umbral shadow of the Earth right through its center.

Totality on Friday lasts for 1 hour, 42 minutes and 57 seconds. This was last beat on July 16th, 2000 with a duration of 1 hour, 46 minutes and 24 seconds (2001 is technically the first year of the 21st century). The duration for Friday’s eclipse won’t be topped until June 9th 2123 (1 hour 46 minutes six seconds), making it the longest for a 123 year span.

The longest total lunar eclipse over the span of 5,000 years from 2000 BC to 3000 AD was on May 31st, 318 AD at 106.6 minutes in duration.

A Minimoon Eclipse

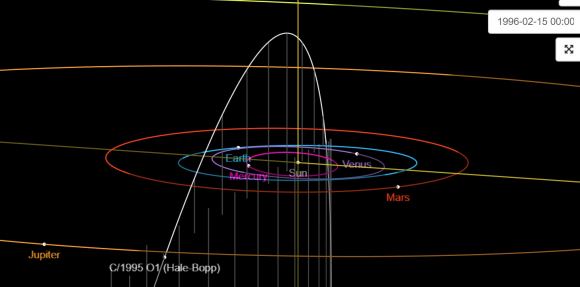

Finally, a third factor is assisting this eclipse in its longevity is the onset of the MiniMoon: The Moon reaches apogee at July 27th, 5:22 UT, 14 hours and 37 minutes prior to Full and the central time of the eclipse. This is the most distant Full Moon of the year for 2018 (406,222 km at apogee) the 2nd most distant apogee for 2018. Apogee on January 15th, beats it out by only 237 kilometers. This not only gives the Moon a slightly smaller size visually at 29.3′, versus 34.1′ near perigee, less than half of the 76′ arcminute diameter of the Earth’s shadow. This also means that the Moon is moving slightly slower in its orbit, making a more stately pass through the Earth’s shadow.

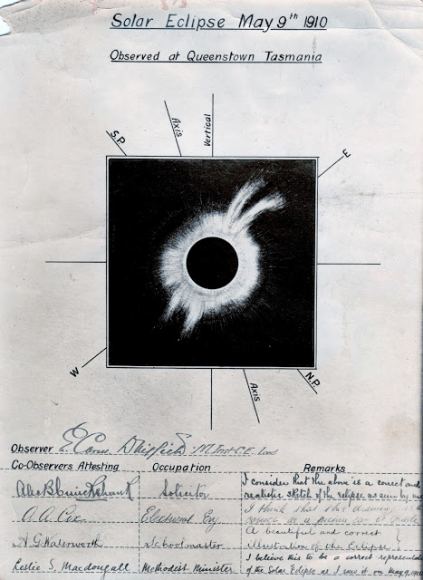

What will the Moon look like during the eclipse? Not all total lunar eclipses are the same, but I’d expect a dark, brick red hue from such a deep eclipse. The color of the Moon during a eclipse is described as its Danjon number, ranging from a bright (4) to dark murky copper color (0) during totality.

Tales of the Saros

This particular eclipse is member 38 of the 71 lunar eclipses in saros series 129, running from June 10th, 1351 all the way out to the final eclipse in the series on July 24th, 2613 AD. If you caught the super-long July 16th, 2000 eclipse (the longest for the 20th century) then you saw the last one in the series, and the next one for the series occurs on August 7th, 2036. Collect all three, and you’ve completed a triple exeligmos series, a fine word in Scrabble to land on a triple word score.

Photographing the Moon

If you can shoot the Moon, you can shoot a total lunar eclipse, though a minimum focal length lens of around 200mm is needed to produce a Moon much larger that a dot. The key moment is the onset of totality, when you need to be ready to rapidly dial the exposure settings down from the 1/100th of a second range down to 1 second or longer. Be careful not to lose sight of the Moon in the viewfinder all together!

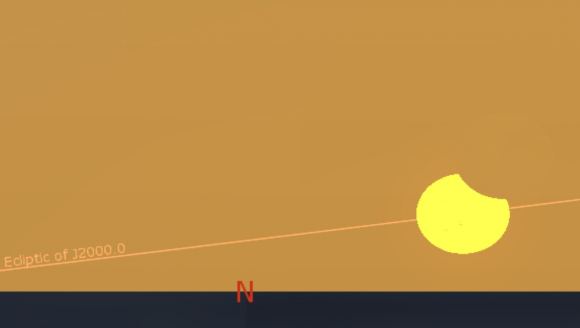

Are you watching the eclipse during moonrise or moonset? This is a great time to shoot the eclipsed Moon along with foreground objects… you can also make an interesting observation around this time, and nab the eclipsed Moon and the Sun above the local horizon at the same time in what’s termed a selenelion. This works mainly because the Earth’s shadow is larger than the apparent diameter of the Moon, allowing it to be cast slightly off to true center after sunrise or just before sunset. Gaining a bit of altitude and having a low, flat horizon helps, as the slight curve of the Earth also gives the Sun and Moon a tiny boost. For this eclipse, the U2-U3 umbral contact zone for a selenelion favors eastern Brazil, the UK and Scandinavia at moonrise, and eastern Australia, Japan and northeastern China at moonset.

Incidentally, a selenelion is the second visual proof you see during a lunar eclipse that the Earth is indeed round, the first being the curve of the planet’s shadow seen at all angles as it falls across the Moon.

Another interesting challenge would be to capture a transit of the International Space Station during the eclipse, either during the partial or total phases… to our knowledge, this has never been done during a lunar eclipse. This Friday, South America gets the best shots at a lunar eclipse transit of the ISS:

Be sure to check CalSky for a transit near you.

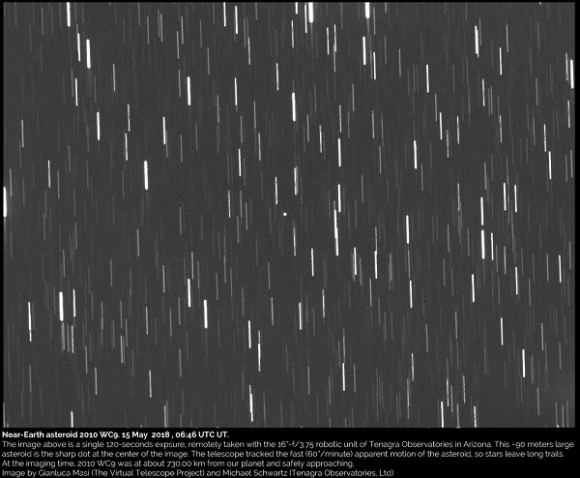

Live on the wrong continent, or simply have cloudy skies? Gianluca Masi and the Virtual Telescope Project 2.0 have you covered, with a live webcast of the eclipse from the heart of Rome, Italy on July 27th starting at 18:30 UT.

Be sure to catch Friday’s total lunar eclipse, either in person or online… we won’t have another one until January 21st, 2019.

Learn about eclipses, occultations, the motion of the Moon and more in our new book: Universe Today’s Guide to the Cosmos: Everything You Need to Know to Become an Amateur Astronomer now available for pre-order.