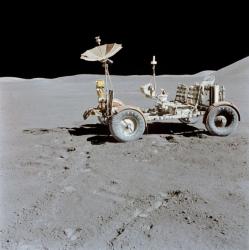

Take a look at any construction project or surface mining operation here on Earth and likely there will be bulldozers, loaders, and trucks; all essential in excavating and building structures. But as we look to the future with NASA’s Vision for Space Exploration which calls for a return to the Moon to build bases and habitats, how will heavy construction and excavation be accomplished on the lunar surface?

Caterpillar Inc., a company known for their heavy earth moving machines and the world’s leading manufacturer of construction and mining equipment, is looking to tackle that issue. They’ve partnered with NASA to create technology that could benefit construction and mine workers everywhere in the future, whether they grab a hard-hat or a space helmet on their way to work.

Caterpillar was one of 38 companies awarded seed funds as part of NASA’s Innovative Partnerships Program (IPP). Projects are selected for this program because of their potential to advance key technologies that will help meet NASA’s critical needs for the future.

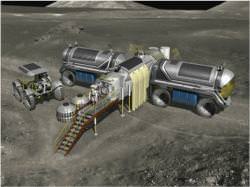

Caterpillar has proposed a multi-terrain loader for lunar surface development. Currently, they are working with NASA to develop the technology to augment existing earth moving equipment with sensors and on-board processors to provide time-delayed tele-operational control.

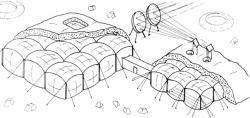

The loader would be able to undertake regolith moving such as grading, leveling, trenching, strip-mining, excavating and habitat covering. It also could be used for construction of lunar bases, the deployment or relocation of surface assets, as well as for mobility on the Moon.

Why is a down-to-earth company like Caterpillar interested in the Moon?

“The way we looked it, there are technologies that are needed on both the Earth and the moon,” Michele Blubaugh, Manager of Intelligence Technology Services at Caterpillar, told Universe Today. “We looked at autonomous operations of equipment as being the same type of technology that could be used on the moon as well as in a mining application. We have the same end result as NASA.”

That end result is to remove operators of construction equipment from a dangerous situation, whether it’s a machine operator in a dangerous mine environment or whether the operator is an astronaut on the lunar surface trying to excavate habitat sites.

There are two types of tele-operation. One is remote operation, where control of the machine is done with a remote operating system. There would be either a vision system on board or someone could actually see the machine as its operating. The other is autonomous operation, where the desired work is programmed and offloaded onto the machine and then the machine carries out the work without anyone interfacing with the machine, either remotely or directly. The machine would read the program at the site, positions itself, have avoidance capabilities to avoid rocks or any object that might be in the way, operating on its own to complete the given mission.

Caterpillar is working on both types of operation. “It’s one step to the next,” said Blublaugh. “You need both of those technologies developed, with remote operations first, and then the ultimate is autonomous operations.”

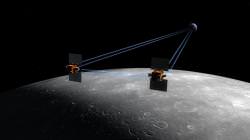

They are also investigating working remotely or autonomously on the Moon from Earth, and dealing with the six second time delay between the earth and the moon.

Currently, there are two multi-terrain loaders, the Caterpillar 287 C Skid Steer loader, outfitted with duplicates of the remote technology. One is located at Caterpillar’s proving grounds near their headquarters in Peoria, Illinois and the other is at the rock yard at Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. “That way we can develop it together,” said Blubaugh. “When we’re doing something, we each have a machine so we know how something reacts.”

The technology is still in the development stage. “We did some initial basic demonstrations when we delivered the machine in May of 2007 at JSC,” Blubaugh said. “A group of us went down, and the people at JSC were taught to use the machine and what the capabilities were, and we discussed the interfaces between the different types of technology.” In the summer of 2008, the group from Caterpillar will return to JSC to do an interim demonstration at a desert site.

Both machines have been undergoing tests. “Within the contract, NASA is responsible for some of the development and Caterpillar is responsible for other portions,” said Blubaugh, “and then there are things that we do jointly to move the technology along faster, so everyone benefits. JSC gets benefits of our facilities and our engineers working on technology, and vice versa, CAT gets benefits from the folks working at JSC and the technology they have and their facilities, so it’s a mutually beneficial relationship between Johnson and CAT.”

Caterpillar has another contract proposal going to JSC shortly that takes the project to the next level.

“We’ll look to do berming, which is building an earthen berm around a site, leveling and sensing the position of the blade,” said Blubaugh. “We take the technology that we have accomplished today and take it to the next level. It’s almost an annual step by step process in the development and our target date for having a signature demo showcasing this type of technology autonomy, being able to load a program into the machine and having it operate all by itself is targeted for 2012.”

Since the 287 C skid loader is extremely heavy and runs on a diesel engine, it couldn’t be used on the moon. A prototype of a lunar loader-type vehicle is being developed by NASA and Caterpillar is assisting with developing the blade. “So, we’ll be involved in the project all the way along as it develops,” said Blubaugh.

The one-year IPP projects involve collaboration between NASA and a company from the private sector, academia or another government laboratory. All IPP companies address technology barriers with cost-shared, joint-development programs.

Other examples of NASA IPP research areas include the pursuit of improved engine performance and reduced emissions for aeronautics research; high-temperature materials for lunar lander engines, optics to lower error rates of future space telescopes, and a glass bubble insulation demonstration for cryogenic tanks.

With a total cost of the Caterpillar project of just under $1,000,000, Caterpillar is estimated to contribute about 45% and NASA 55%. For the entire NASA’s Innovative Partnership Program $9 million in funding comes from NASA’s Technology Transfer Partnerships budget, $13 million is provided by NASA sources in programs, projects, or field centers, and $12 million from external partners for a total combined financial commitment of $34 million.

“A lot of us at Caterpillar grew up in the time of the first space development,” said Blubaugh, “it’s quite exciting for us to be a part of this. Plus, it’s just a good investment in the future.”