[/caption]Some of you may know, we recently launched a new “Ask” feature here at Universe Today. Our inaugural launch features Dr. Alan Stern, Principal Investigator for the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt. We collected your questions in our initial post and passed them along to Dr. Stern who graciously took the time to answer them.

Here are the questions picked by you, the readers, and Dr. Stern’s responses. We’d like to thank our readers for making this kick-off a success, as well as Dr. Stern for his participation.

1.) Many sci-fi authors have dreamed of putting some sort of telescope on the surface of Pluto to take advantage of the relative darkness and extreme cold encountered on this distant dwarf planet. How feasible would it be, judging from what we’re learning from the New Horizons expedition, to actually land a spacecraft, or a telescope, on Pluto’s surface? If such a telescope where deployed, how much more effective, if at all, could it be than an instrument like the JWST?

Alan Stern:“Space astronomy has revolutionized the way we look at the universe and is fundamental to modern astrophysics.” There are benefits to getting telescopes out of the atmosphere, and even benefits to getting out of Earth orbit, as in the case of Kepler and someday maybe JWST.

With regard to taking advantage of Pluto’s cold temperature – we’ve gotten really good at cooling down space telescopes. “There would be a benefit to placing a radio telescope on the far side of the Moon, but there’s no real practical reasons to place a telescope on Pluto—particularly given the cost of getting there, other than it being cool.”

2.) Kuiper objects differentiate strongly in color suggesting compositional or perhaps formation differences. Interestingly the color distribution correlates with the two different cold and hot Kuiper populations. Assuming the spectral analysis capability of New Horizon works for identifying the follow up Kuiper objects beyond Pluto-Charon, and given the putative possibility of choosing between several such targets, what type of target would the mission aim for? Would it try to cover as much diversity of objects as possible or is there a certain class of objects that could be important to concentrate on?

A.S: “We have to find Kuiper belt objects within our spacecraft’s fuel supply.” Stern elaborated, stating, “Predictions from our computer models tell us to expect to be able to have perhaps six possible candidates, to choose from, but so far we’ve just begun to search for these and though we’re finding KBOs, none we’ve found are yet are within the fuel supply.”

Stern also added, “Keep in mind our search for candidates isn’t easy – these are 27th magnitude objects which are roughly 50,000 times fainter than Pluto. What we’ll use to select between candidates once we have them are color, orbits, moons, rotational speeds – basically what combination of properties give us the most science for our fuel budget. The longer we wait after the Pluto flyby in July 2015 to make a decision, the more fuel will be consumed, so the “sweet spot” would be to have preliminary candidates in early 2015.”

(UT Note: New Horizons will perform its Pluto flyby in mid-2015 ).

3.) Given the limited funds available, Which do you recommend (Europa or Enceladus) as a suitable target for a mission in the 2025 time-frame in terms of value for money, scientific return, and practicality, and what kind of mission do you propose (lander vs. orbiter) ?

A.S: “Every scientist has their own judgment of what would make a good outer system flagship mission, or the best world to perform a series of missions that would equal a flagship mission.” Dr. Stern’s opinion is to explore Titan first, with Enceladus as a secondary target of that mission and Europa last, stating “Titan is the belle of the ball”, citing Titan’s active liquid cycle and thick atmosphere. Stern also added that he believes a mission to Titan would provide the most science per budget dollar.

4.) Four of the craft escaping the Solar System – Pioneers 10 & 11 and Voyagers 1 & 2 – have on board some sort of “message” to any possible extraterrestrials in the unlikely event they find it. Why was not some sort of message like that included on New Horizons, which may be the last (in our lifetimes) craft to also escape the Solar System?

A.S “There are several mementos onboard New Horizons, but no Voyager-like message.” Dr. Stern discussed a promise he made to his team that New Horizons would not be canceled and that he wanted his team focused on the science of the mission. Stern also pointed out that the process of deciding what to place on the Voyager plaques became mired in political correctness, (should the humans have been clothed? What cultures and races should be represented, etc.)

By separating the “icing from the cake”. Stern and his team have been able to concentrate on their main objective—to execute the New Horizons mission for about twenty cents on the dollar, as compared to the Voyager missions. Stern concluded with, “I’m proud that we got this done and that New Horizons is operating perfectly now way out there between Uranus and Neptune and flying almost a million kilometers per day toward the Pluto system.”

5.) Are any present or foreseeable technologies being considered for exploring the depths of our four “gas giant” planets?

A.S “There are no serious proposals to put a probe into one of the giant planets now, or even any call for such in the recent decadal survey for planetary missions. Keep in mind, though, that the Juno mission (now en route to Jupiter ) will use powerful remote sensing techniques to probe Jupiter from orbit around it to greater depths than the Galileo probe (which actually entered Jupiter’s atmosphere).”

6.) Why was it considered “urgent” to get to Pluto before the atmosphere refroze?

A.S “We have three “Group 1″ objectives for New Horizons. Map the surface, map the composition, and assay the atmosphere.” Stern referred to the objectives as a “three legged stool” in that no one objective could be omitted and still justify the mission, adding “so we need to accomplish that.. we need to get there before the atmosphere collapses”. Stern also referred to Pluto’s atmosphere as “very different from any other planet yet studied”, hence its inclusion as one of the three “Group 1” objectives.

7.) The Dawn mission to Vesta has shown us a body that was much less round than expected. Do you think it is possible that New Horizons will surprise us about Pluto, to the same degree? Please compare the expectations of the New Horizons fly by, to the early images of Vesta from Dawn.

A.S “With New Horizons being the first mission to Pluto, we will be surprised—after all, we’re always surprised on first reconnaissance flybys”. Stern added, “With Mariner 10, we discovered Mercury was all core, with Voyager we discovered volcanos and geysers across the outer solar system, and of course we were surprised when craters and river valleys were discovered by early Mars probes.”

Regarding Pluto, Stern stated “Pluto is the first discovered and soon to be reconnoitered of the most plentiful class of planets, while I’m not big on making predictions, I will say that what we will find will certainly be, well, wonderful.”

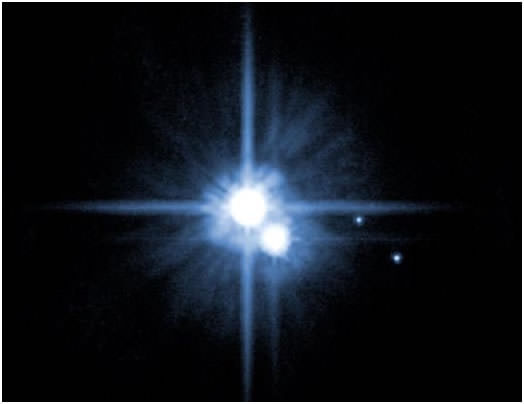

9.) Can new horizons now take more detailed photos of Pluto than HST? If not, when does it get close enough?

A.S “Great question! We actually thought about that a lot when designing New Horizons. One of our instruments, LORRI (Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager – http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/spacecraft/sciencePay.html) will provide us with views better than HST around April of 2015, and we expect to have about twenty weeks (10 weeks before, 10 weeks after the Pluto flyby) when we “own” the Pluto system — and I can guarantee the best images we hope to make should be as good as Landsat images of Earth!”

That wraps up our interview with Dr. Alan Stern. Once again, we at Universe Today would like to thank Dr. Stern for his gracious participation. If you’d like to learn more about the New Horizons mission to Pluto and The Kuiper Belt, visit: http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/index.php

Next month, we’ll be having an “Ask an Astronaut” feature with Mike Fossum, Commander of Expedition 29 on the International Space Station. Stay tuned!