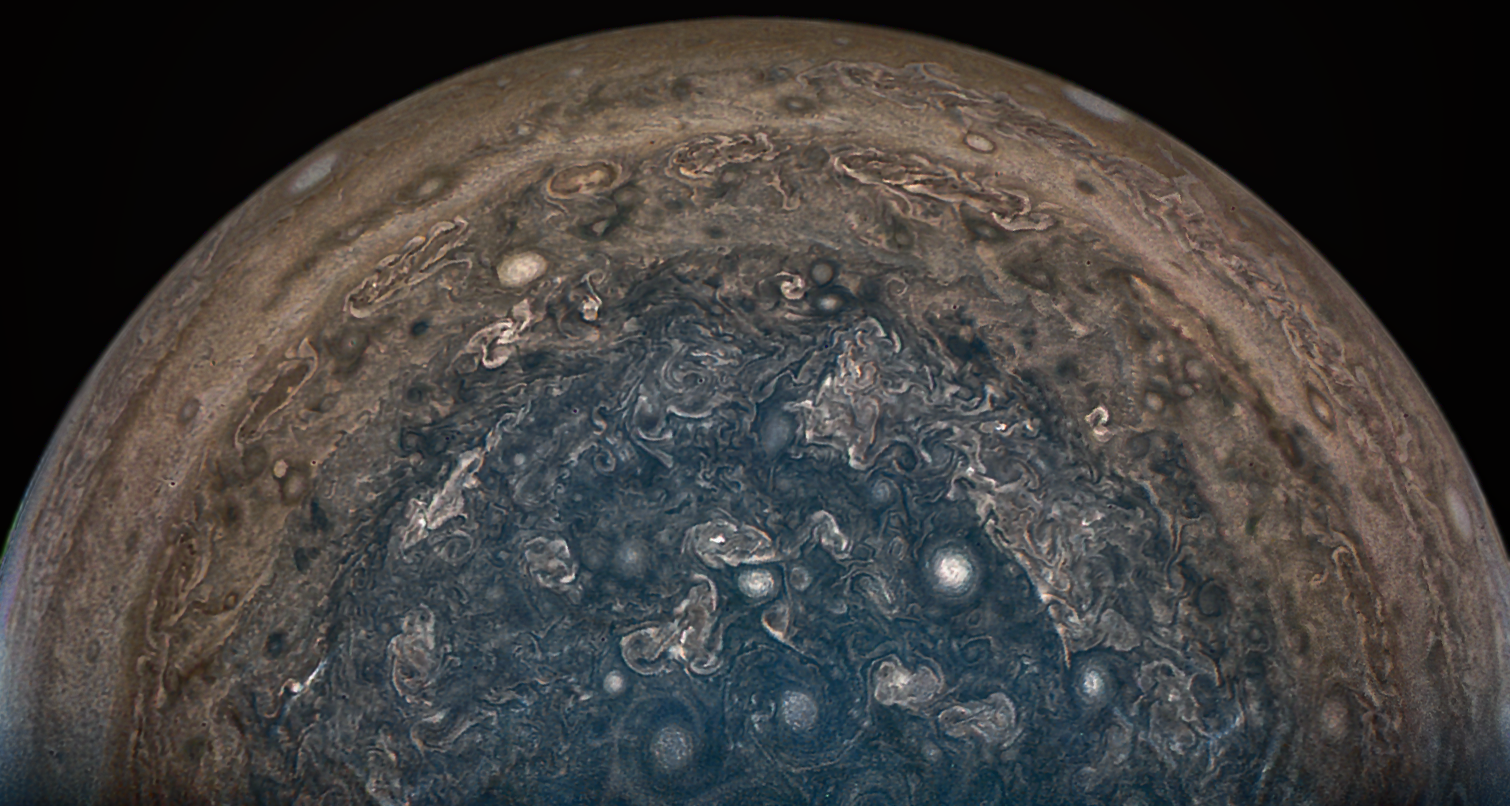

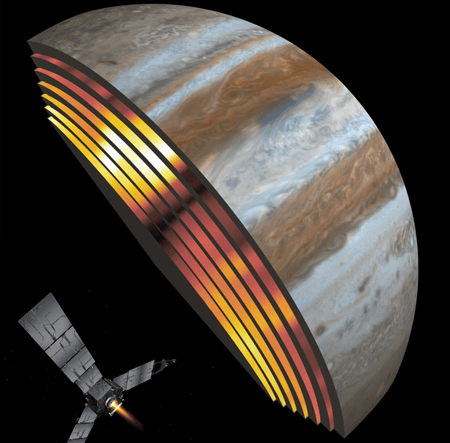

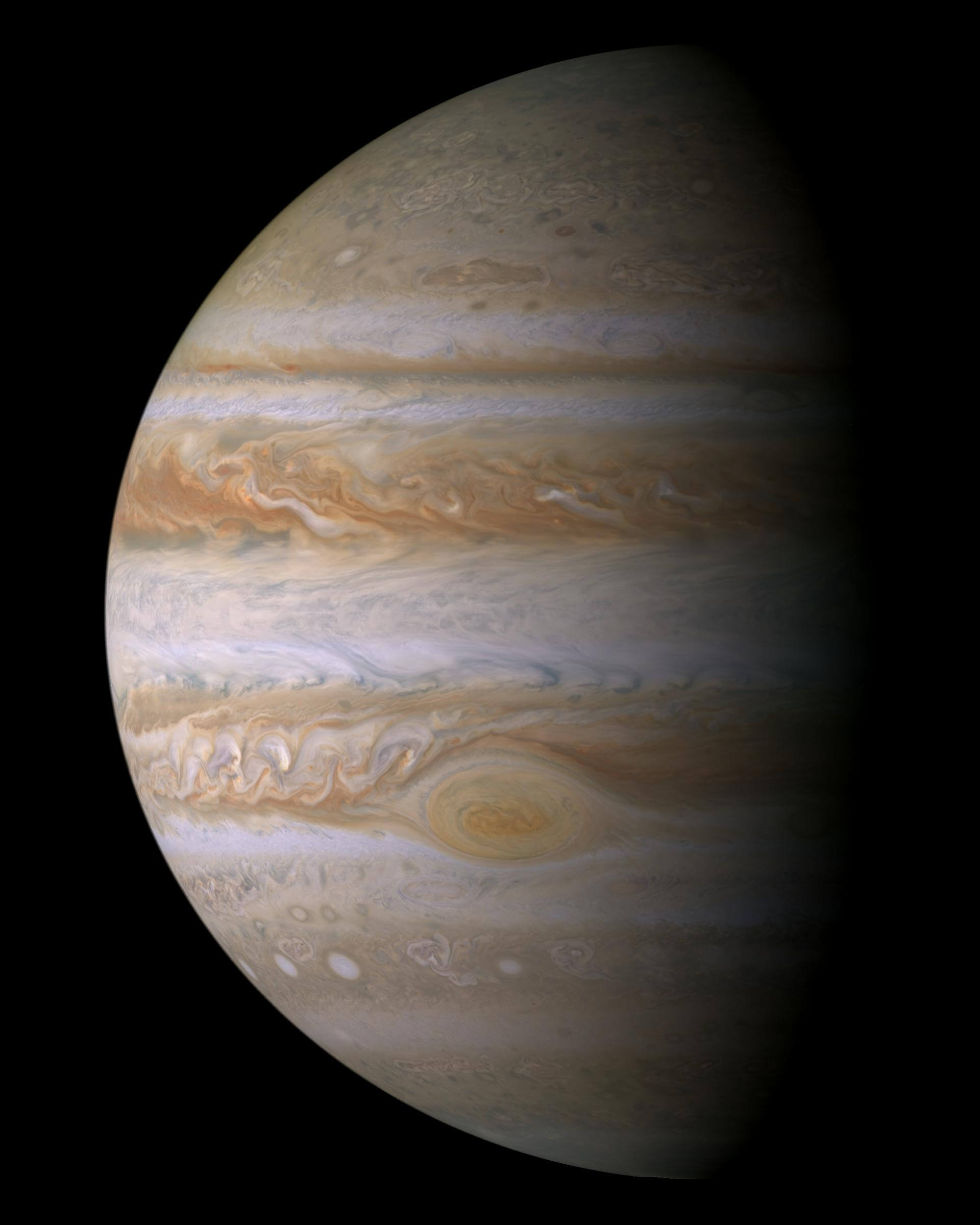

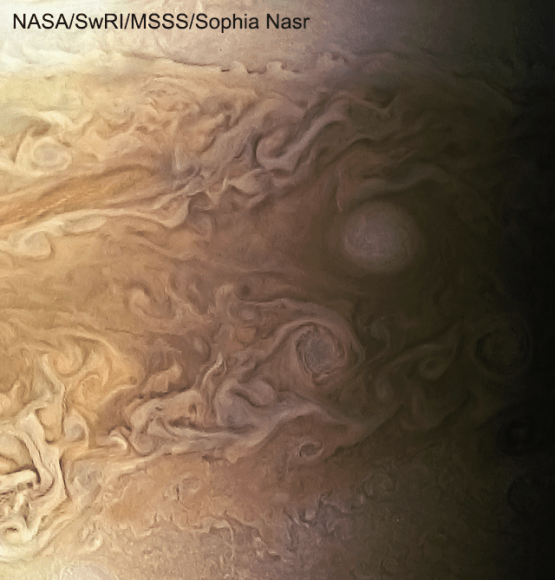

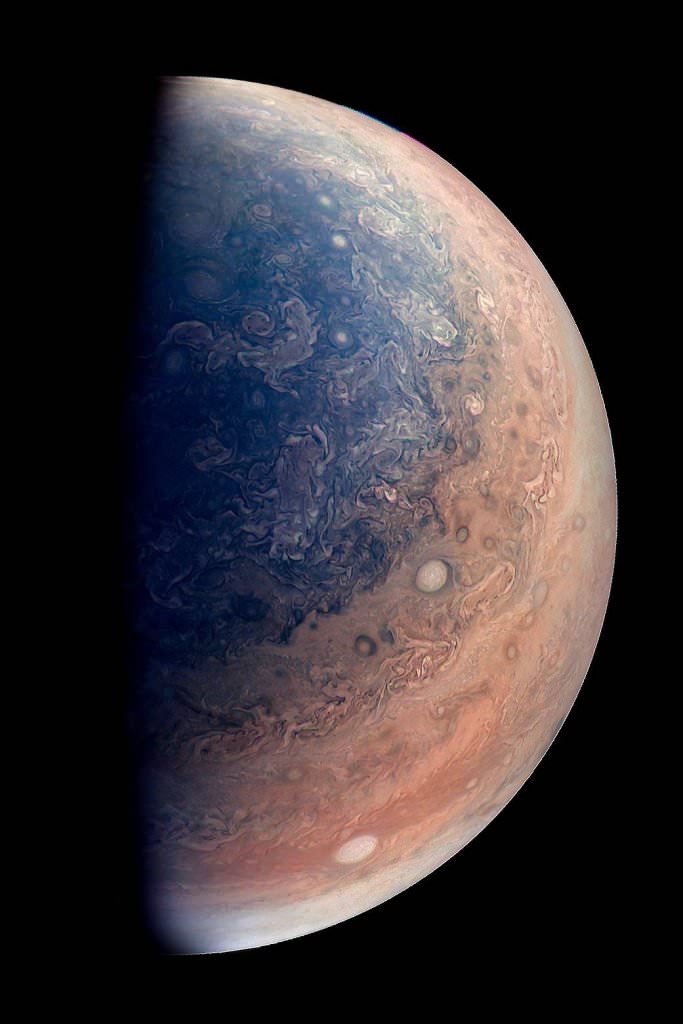

Since it arrived in orbit around Jupiter in July of 2016, the Juno mission has been sending back vital information about the gas giant’s atmosphere, magnetic field and weather patterns. With every passing orbit – known as perijoves, which take place every 53 days – the probe has revealed things about Jupiter that scientists will rely on to learn more about its formation and evolution.

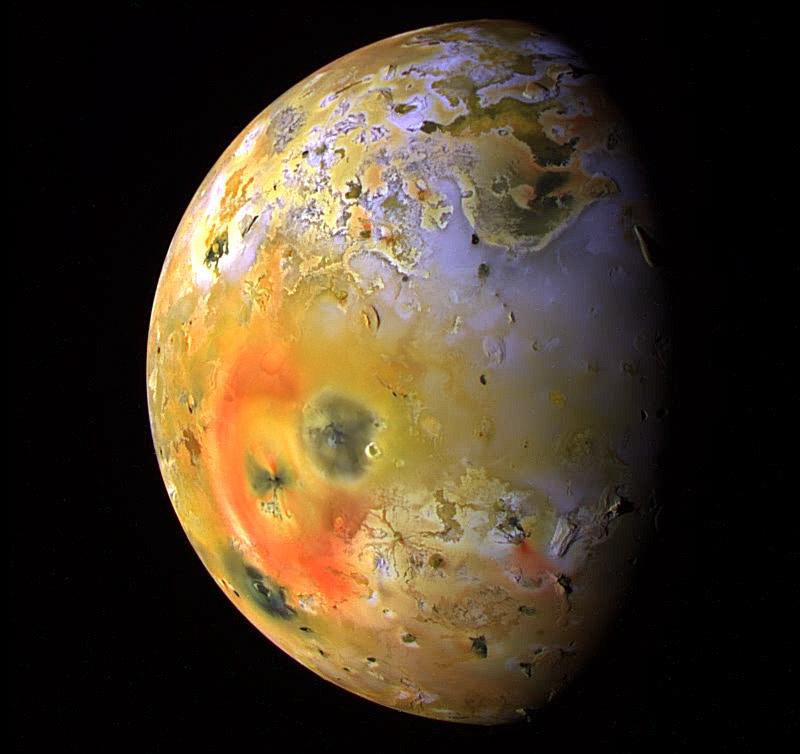

Interestingly, some of the most recent information to come from the mission involves how two of its moons affect one of Jupiter’s most interesting atmospheric phenomenon. As they revealed in a recent study, an international team of researchers discovered how Io and Ganymede leave “footprints” in the planet’s aurorae. These findings could help astronomers to better understand both the planet and its moons.

The study, titled “Juno observations of spot structures and a split tail in Io-induced aurorae on Jupiter“, recently appeared in the journal Science. The study was led by A. Mura of the International Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) and included members from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the Italian Space Agency (ASI), the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), and multiple universities.

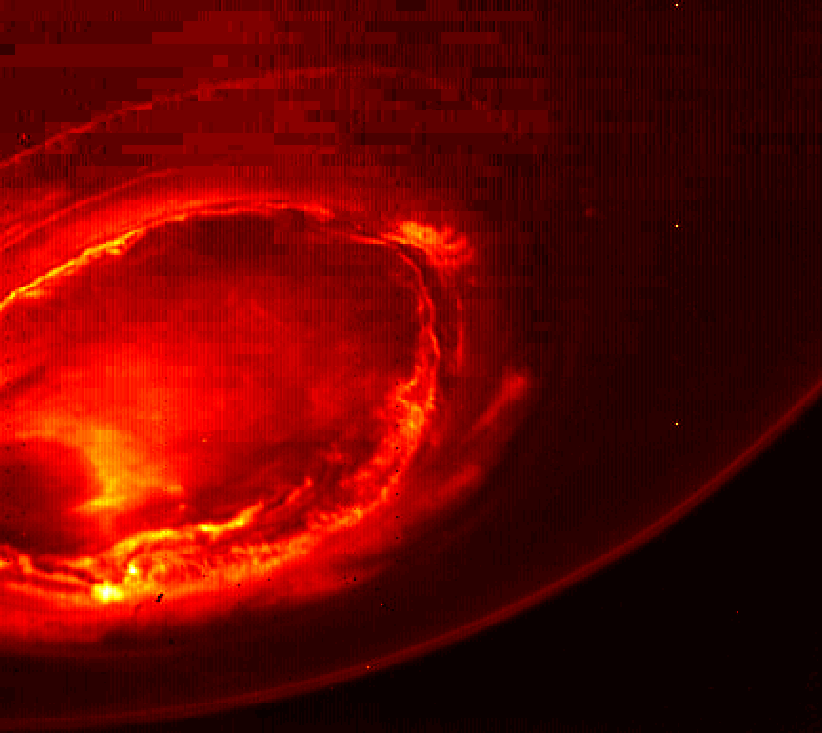

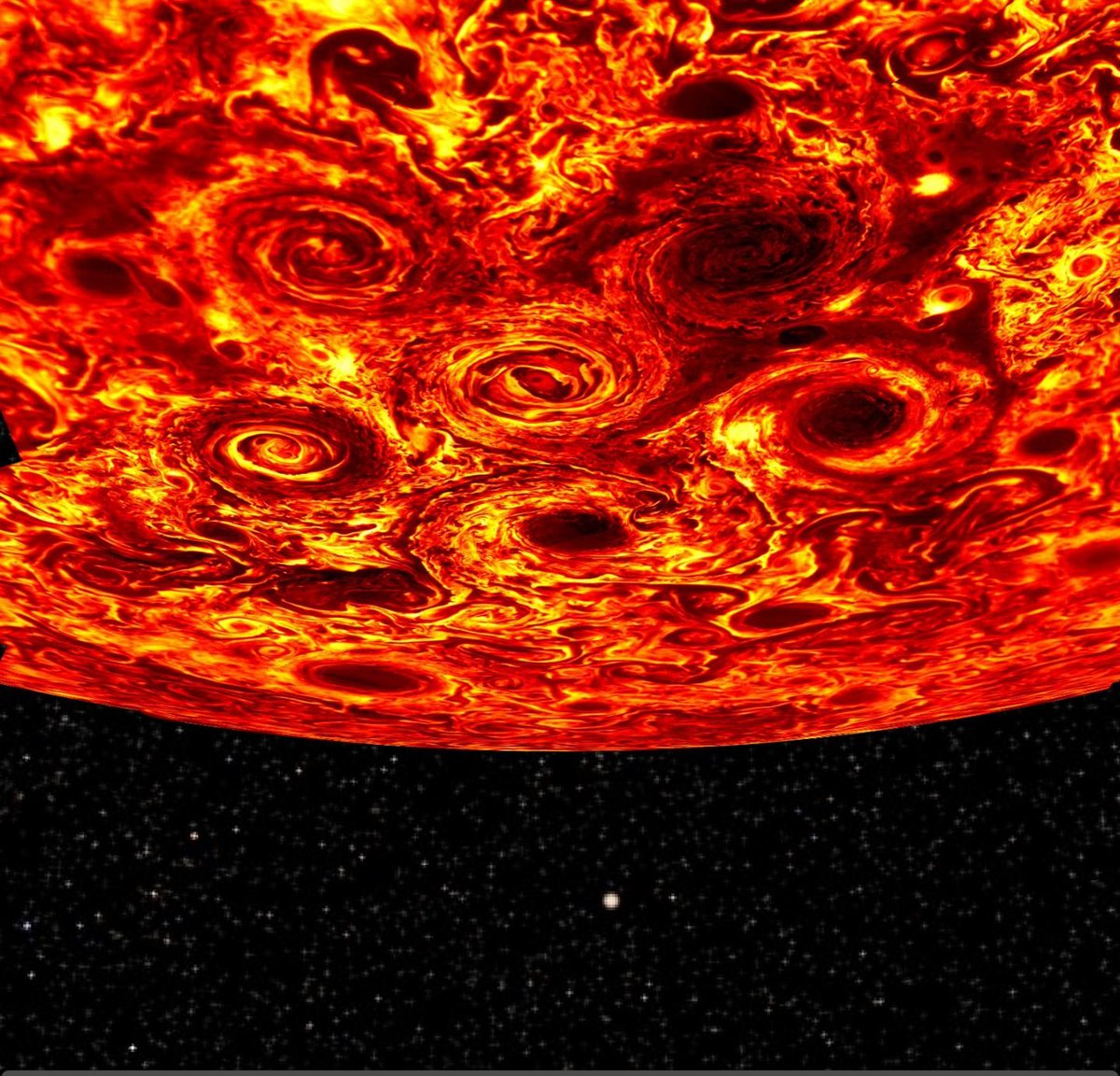

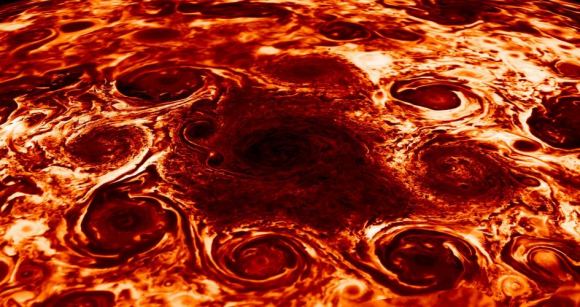

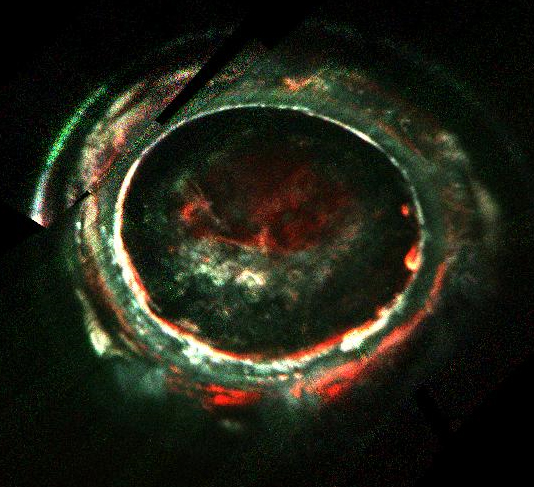

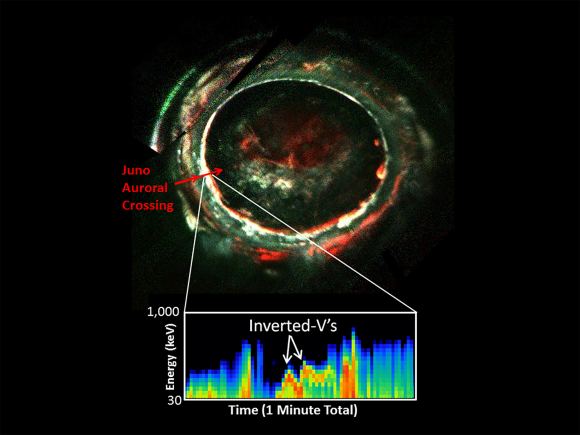

Much like aurorae here on Earth, Jupiter’s aurorae are produced in its upper atmosphere when high-energy electrons interact with the planet’s powerful magnetic field. However, as the Juno probe recently demonstrated using data gathered by Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS) and Jovian Energetic Particle Detector Instrument (JEDI), Jupiter’s magnetic field is significantly more powerful than anything we see on Earth.

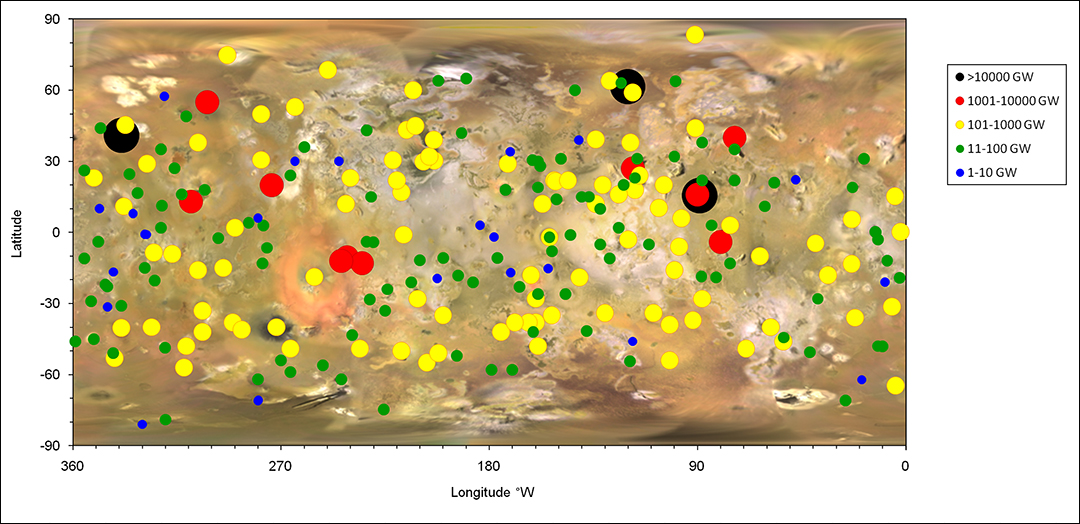

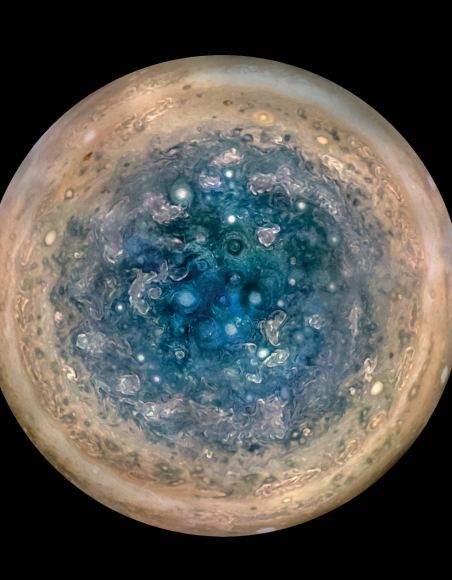

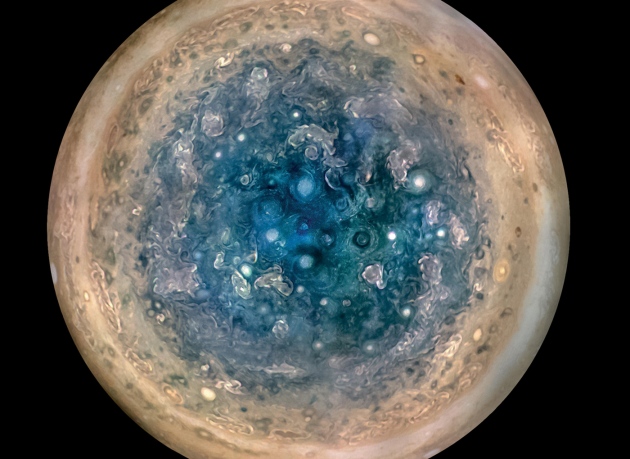

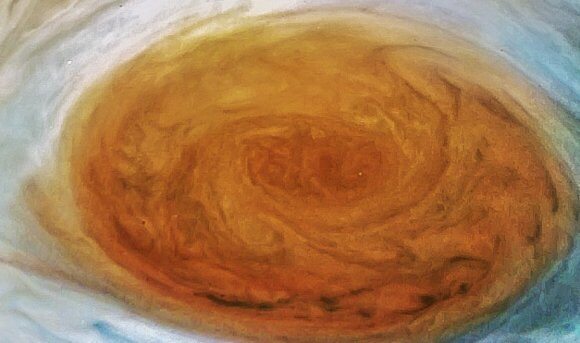

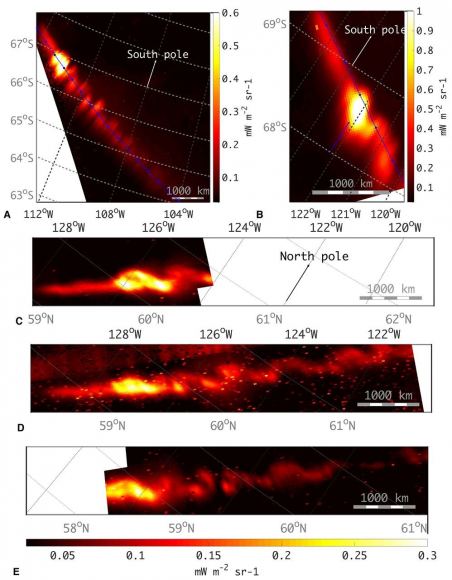

In addition to reaching power levels 10 to 30 times greater than anything higher than what is experienced here on Earth (up to 400,000 electron volts), Jupiter’s norther and southern auroral storms also have oval-shaped disturbances that appear whenever Io and Ganymede pass close to the planet. As they explain in their study:

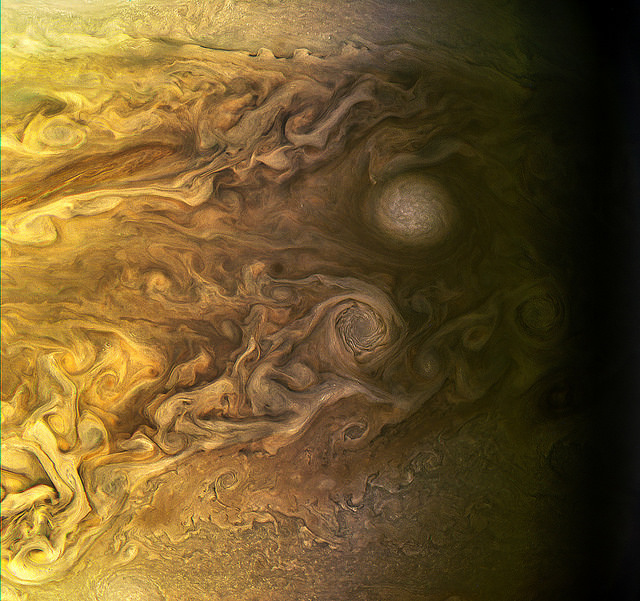

“A northern and a southern main auroral oval are visible, surrounded by small emission features associated with the Galilean moons. We present infrared observations, obtained with the Juno spacecraft, showing that in the case of Io, this emission exhibits a swirling pattern that is similar in appearance to a von Kármán vortex street.”

A Von Kármán vortex street, a concept in fluid dynamics, is basically a repeating pattern of swirling vortices caused by a disturbance. In this case, the team found evidence of a vortex streaming for hundreds of kilometers when Io passed close to the planet, but which then disappeared as the moon moved farther away from the planet.

The team also found two spots in the auroral belt created by Ganymede, where the extended tail from the main auroral spots eventually split in two. While the team was not sure what causes this split, they venture that it could be caused by interaction between Ganymede and Jupiter’s magnetic field (since Ganymede is the only Jovian moon to have its own magnetic field).

These features, they claim, suggest that magnetic interactions between Jupiter and Ganymede are more complex than previously thought. They also indicate that neither of the footprints were where they expected to find them, which suggests that models of the planet’s magnetic interactions with its moons may be in need of revision.

Studying Jupiter’s magnetic storms is one of the primary goals of the Juno mission, as is learning more about the planet’s interior structure and how it has evolved over time. In so doing, astronomers hope to learn more about how the Solar System came to be. NASA also recently extended the mission to 2021, giving it three more years to gather data on these mysteries.

And be sure to enjoy this video of the Juno mission, courtesy of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory: