[/caption]

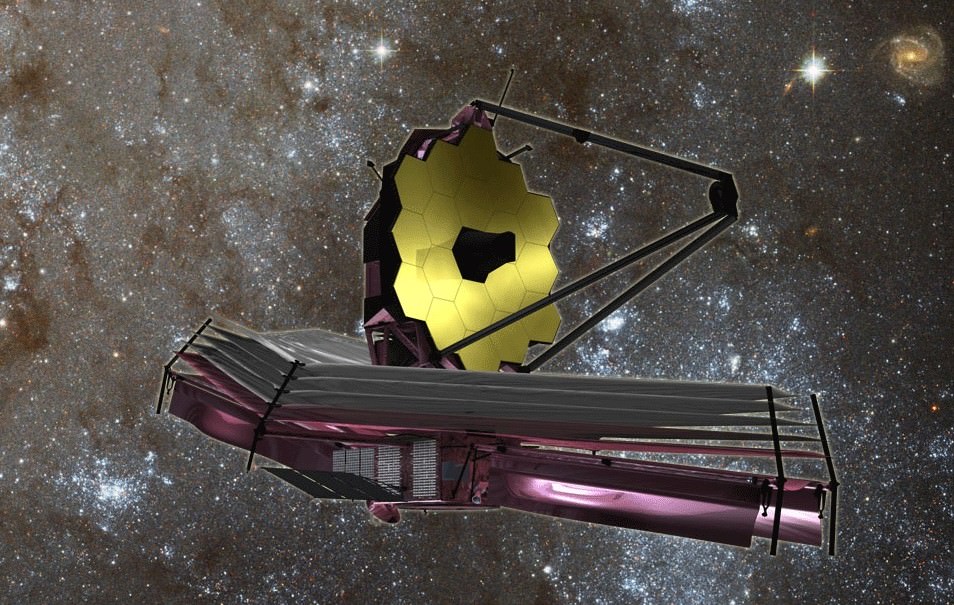

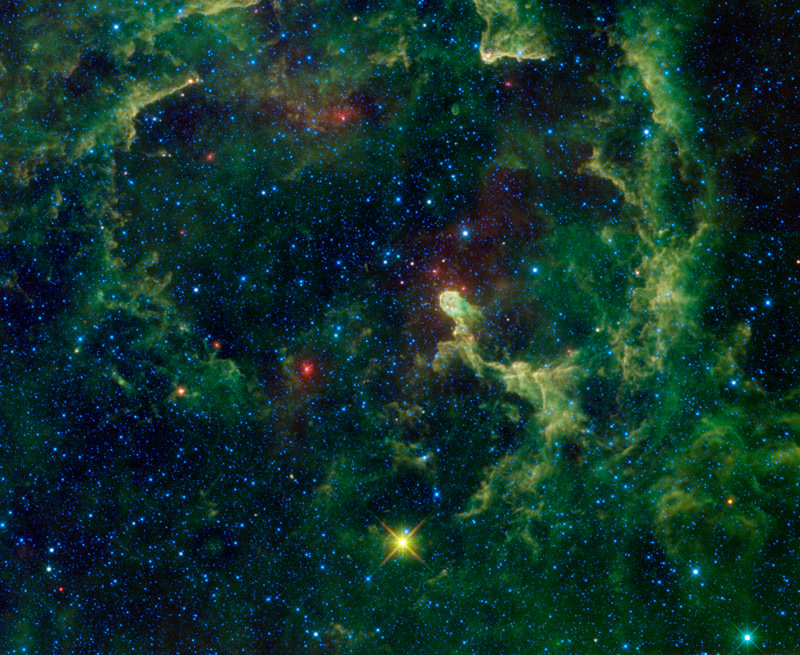

The James Webb Space Telescope or JWST has long been touted as the replacement for the Hubble Space Telescope. The telescope is considered to be the one of the most ambitious space science projects ever undertaken – this complexity may be its downfall. Cost overruns now threaten the project with cancellation. Despite these challenges, the telescope is getting closer to completion. As it stands now, the telescope has served as a technical classroom on the intricacies involved with such a complex project. It has also served to develop new technologies that are used by average citizens in their daily lives.

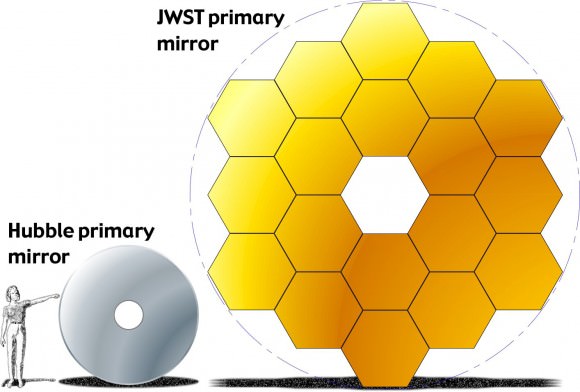

Although compared to Hubble, the two telescopes are dissimilar in a number of ways. The JWST is three times as powerful as Hubble in its infrared capabilities. JWST’s primary mirror is 21.3 feet across (this provides about seven times the amount of collecting power that Hubble currently employs).

The JWST’s mirrors were polished using computer modeling guides that allowed engineers to predict that they will enter into the proper alignment when in space. Each of the mirrors on the JWST has been smoothed down to within 1/1000th the thickness of a human hair. The JWST traveled to points across the country to assemble and test the JWST’s various components.

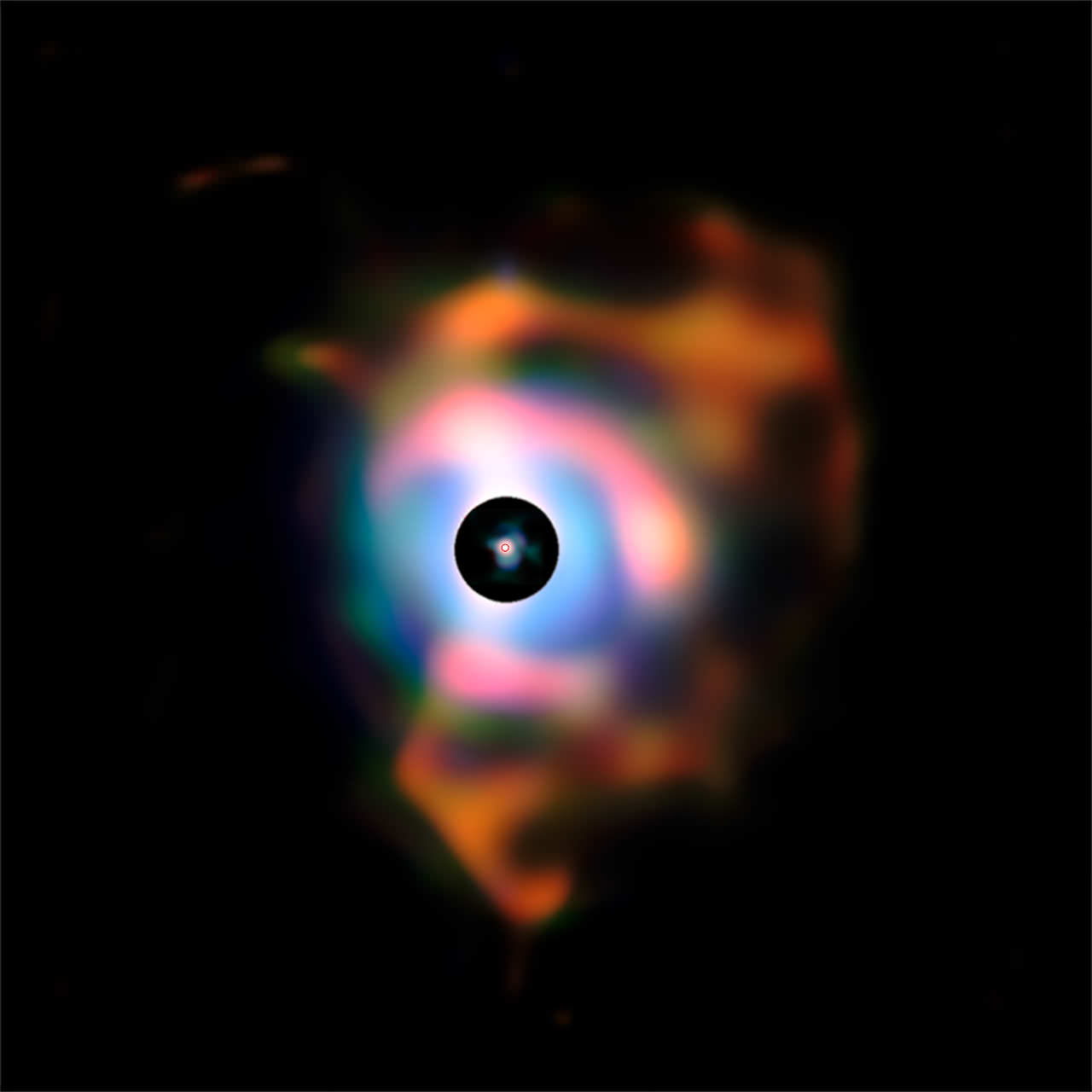

Eventually the mirrors were then sent to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Once there they measured how the mirrors reacted at extremely cold temperatures. With these tests complete, the mirrors were given a thin layer of gold. Gold is very efficient when it comes to reflecting light in the infrared spectrum toward the JWST’s sensors.

The telescope’s array of mirrors is comprised of beryllium, which produces a lightweight and more stable form of glass. The JWST requires lightweight yet strong mirrors so that they can retain their shape in the extreme environment of space. These mirrors have to be able to function perfectly in temperatures reaching minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit.

After all of this is done, still more tests await the telescope. It will be placed into the same vacuum chamber that tested the Apollo spacecraft before they were sent on their historic mission’s to the moon. This will ensure that the telescopes optics will function properly in a vacuum.

With all of the effort placed into the JWST – a lot of spinoff technology was developed that saw its way into the lives of the general populace. Several of these – had to be invented prior to the start of the JWST program.

“Ten technologies that are required for JWST to function did not exist when the project was first planned, and all have been successfully achieved. These include both near and mid-infrared detectors with unprecedented sensitivity, the sunshield material, the primary mirror segment assembly, the NIRSpec microshutter array, the MIRI cryo-cooler, and several more,” said the James Webb Space Telescope’s Deputy Project Scientist Jason Kalirai. Kalirai holds a PhD in astrophysics and carries out research for the Space Telescope Science Institute. “The new technologies in JWST have led to many spinoffs, including the production of new electric motors that outperform common gear boxes, design for high precision optical elements for cameras and cell phones, and more accurate measurements of human vision for people about to undergo Laser Refractive Surgery.”

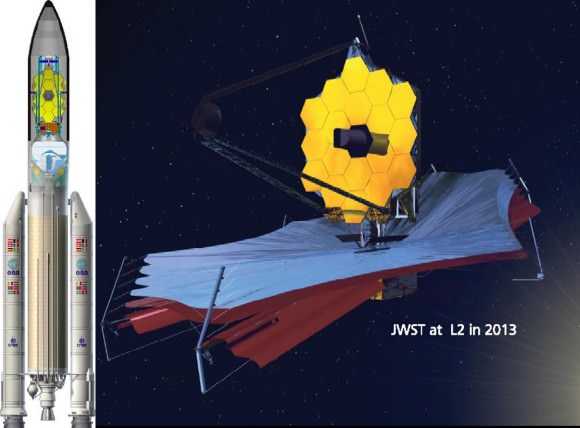

If all goes according to plan, the James Webb Space Telescope will be launched from French Guiana atop the European Space Agency’s Arianne V Rocket. The rationale behind the Ariane V’s selection was based on capabilities – and economics.

“The Ariane V was chosen as the launch vehicle for JWST at the time because there was no U.S. rocket with the required lift capacity,” Kalirai said. “Even today, the Ariane V is a better tested vehicle. Moreover, the Ariane is provided at no cost by the Europeans while we would have had to pay for a U.S. rocket.”

It still remains to be seen as to whether or not the JWST will even fly. As of July 6 of this year the project is slated to be cancelled by the United States Congress. The James Webb Space Telescope was initially estimated at costing $1.6 billion. As of this writing an estimated $3 billion has been spent on the project and it is has been estimated that the telescope is about three-quarters complete.