Whenever the question is asked, what is the highest point on planet Earth?, people naturally assume that the answer is Mt. Everest. In fact, so embedded is the notion that Mt. Everest is the highest point on the world that most people wouldn’t even think twice before answering. And even when we talk of other huge mountains in the Solar System (like Mars’ Olympus Mons), we invariably compare them to Mt. Everest.

But in truth, Everest does not hold the record for being the highest point on Earth. Due to the nature of our planet – which is not shaped like a perfect sphere but an oblate spheroid (i.e. a sphere that bulges at the center) – points that are located along the equator are farther away than those located at the poles. When you factor this in, Everest and the Himalayas find themselves falling a bit short!

Earth as a Sphere:

The understanding that Earth is spherical is believed to have emerged during the 6th century BCE in ancient Greece. While Pythagoras is generally credited with this theory, it is equally likely that it emerged on its own as a result of travel between Greek settlements – where sailors noticed changes in what stars were visible at night based on differences in latitudes.

By the 3rd century BCE, the idea of a spherical Earth began to become articulated as a scientific matter. By measuring the angle cast by shadows in different geographical locations, Eratosthenes – a Greek astronomer from Hellenistic Libya (276–194 BCE) – was able to estimate Earth’s circumference within a 5% – 15% margin of error. With the rise of the Roman Empire and their adoption of Hellenistic astronomy, the view of a spherical Earth became widespread throughout the Mediterranean and Europe.

This knowledge was preserved thanks to the monastic tradition and Scholasticism during the Middle Ages. By the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution (mid 16th – late 18th centuries), the geological and heliocentric views of Earth became accepted as well. With the advent of modern astronomy, precise methods of measurement, and the ability to view Earth from space, our models of its true shape and dimensions have come to be refined considerably.

Modern Models of the Earth:

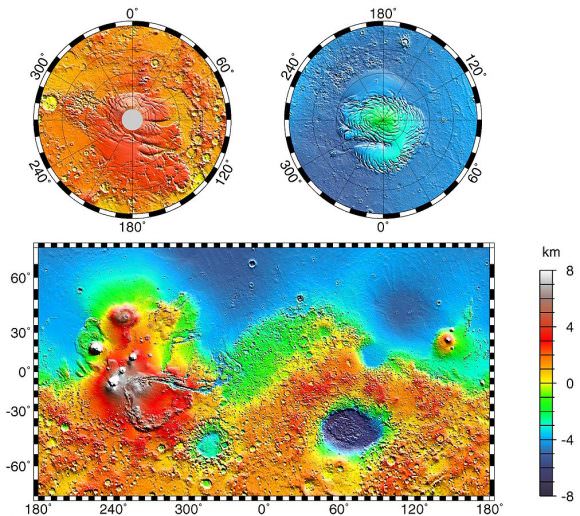

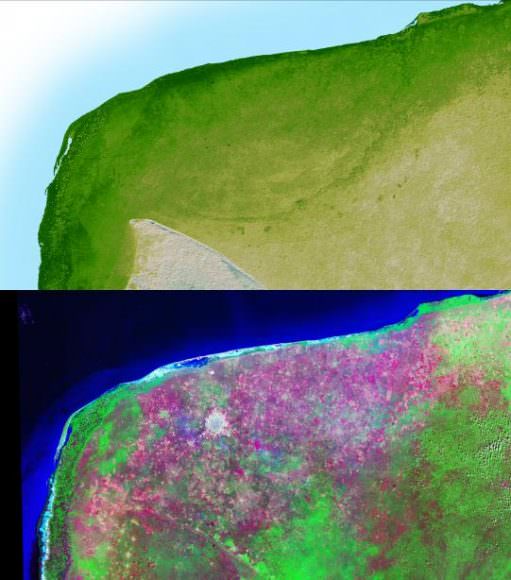

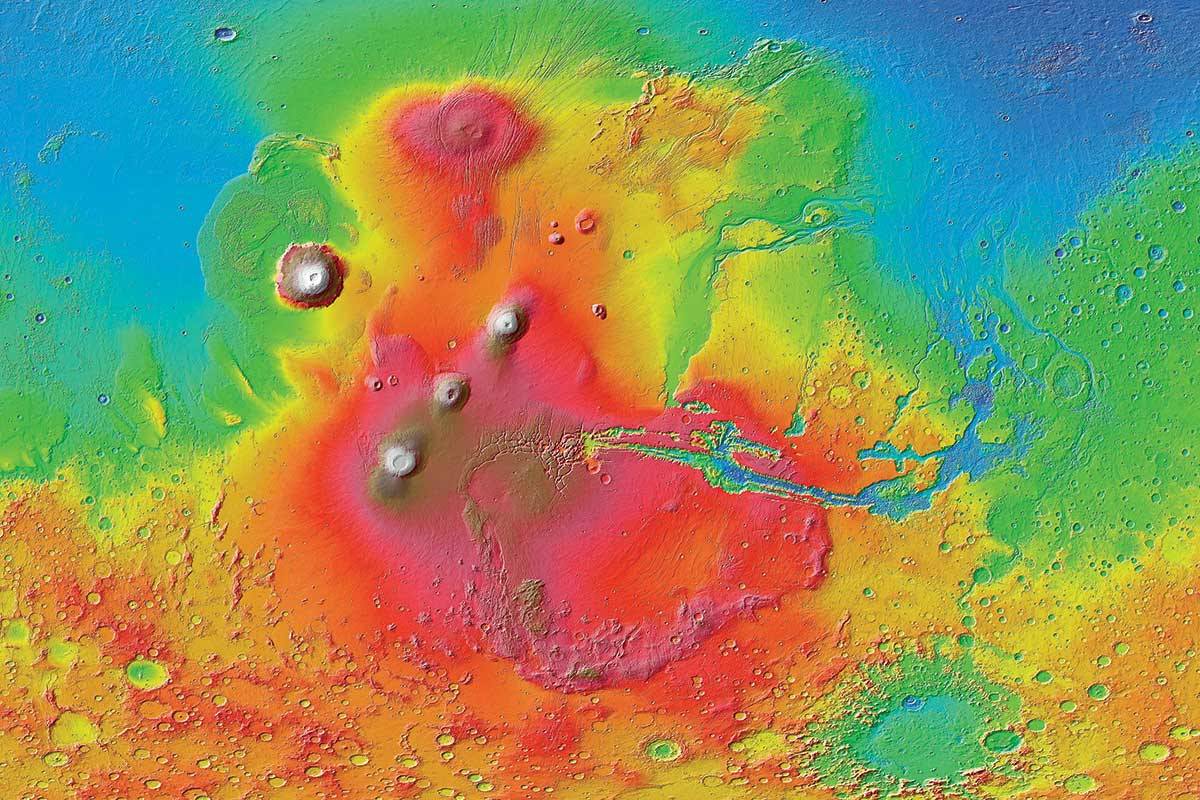

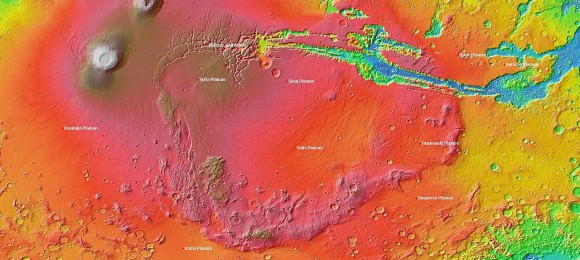

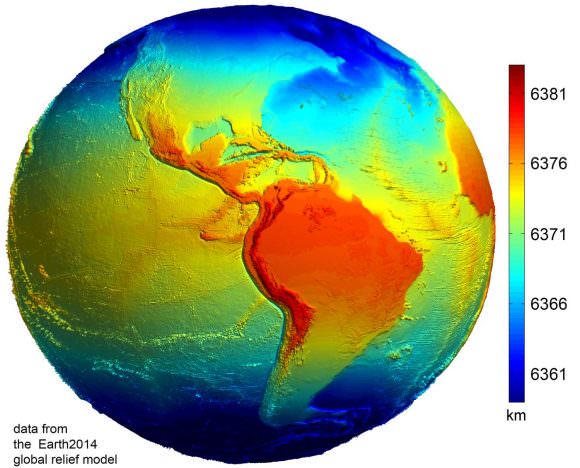

To clarify matters a little, the Earth is neither a perfect sphere, nor is it flat. Sorry Galileo, and sorry Flat-Earthers (not sorry!), but it’s true. As already noted, it is an oblate spheroid, which is a result of the rotation of the Earth. Basically, its spin results in a flattening at the poles and a bulging at its equatorial. This is true for many bodies in the Solar System (such as Jupiter and Saturn) and even rapidly-spinning stars like Altair.

Based on some of the latest measurements, it is estimated that Earth has a polar radius (i.e. from the middle of Earth to the poles) of 6,356.8 km, whereas its equatorial radius (from the center to the equator) is 6,378.1 km. In short, objects located along the equator are 22 km further away from the center of the Earth (geocenter) than objects located at the poles.

Naturally, there are some deviations in the local topography where objects located away from the equator are closer or father away from the center of the Earth than others in the same region. The most notable exceptions are the Mariana Trench – the deepest place on Earth, at 10,911 m (35,797 ft) below local sea level – and Mt. Everest, which is 8,848 meters (29,029 ft) above local sea level. However, these two geological features represent a very minor variation when compared to Earth’s overall shape – 0.17% and 0.14% respectively.

Highest Point on Earth:

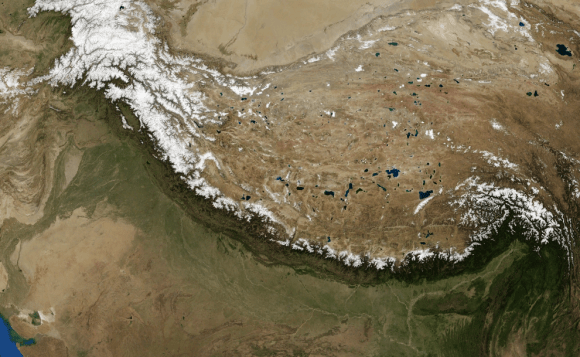

To be fair, Mt. Everest is one of the highest points on Earth, with its peak ascending to an altitude of 8,848 meters (29,029 ft) above sea level. However, due to its location within the Himalayan Mountain Chain in Nepal, some 27° and 59 minutes north of the equator, it is actually lower than mountains located in Ecuador.

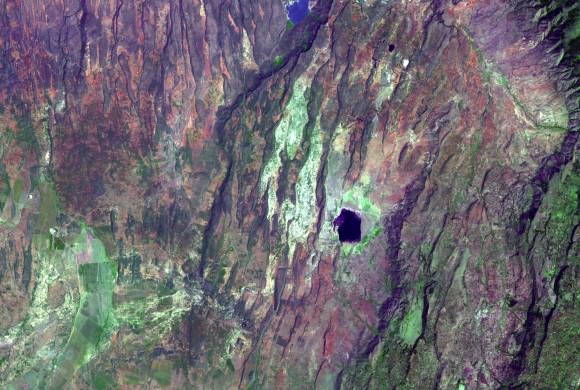

It is here, where the land is dominated by the Andes mountain chain, that the highest point on planet Earth is located. Known as Mt. Chiborazo, the peak of this mountain reaches an attitude of 6,263.47 meters (20,549.54 ft) above sea level. But because it is located just 1° and 28 minutes south of the equator (at the highest point of the planet’s bulge), it receives a natural boost of about 21 km.

In terms of how far they are from the geocenter, Everest lies at a distance of 6,382.3 kilometers (3,965.8 miles) from the center of the Earth while Chimborazo reaches to a distance of 6,384.4 kilometers (3,967.1 miles). That’s a difference of about 2.1 km (1.3 miles), which may not seem like much. But if we’re talking about rankings and titles, it pays to be specific.

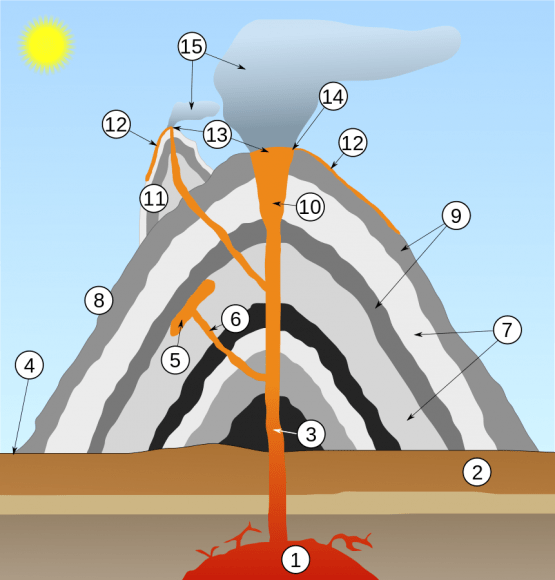

Naturally, there are those who would stress that Mt. Everest is still the tallest mountain, measured from base to peak. Unfortunately, here too, they would be incorrect. That prize goes to Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano located on the island of Hawaii. Measuring 10,206 meters (33,484 ft) from base to summit, it is the highest mountain in the world. However, since its base is several thousand meters below seat level, we only see the top 4,207 m (13,802 ft) of it.

But if one were to say that Everest was tallest mountain based on its altitude, they would be correct. In terms of its summit’s elevation above sea level, Everest is ranked as being as the tallest mountain in the world. And when it comes to the sheer difficulty of ascending it, Everest will always be ranked no. 1, both in the records books and in the hearts of climbers everywhere!

We have written many interesting articles about the Earth and mountains here at Universe Today. Here’s Planet Earth, What is the Earth’s Diameter?, The Rotation of the Earth, and Mountains: How Are They Formed?

For more information, be sure to check out NASA’s Visible Earth, and “Highest Mountain in the World” at Geology.com.

Astronomy Cast also has a great episode on the subject – Episode 51: Earth.