Europa and other ocean worlds in our solar system have recently attracted much attention. They are thought to be some of the most likely places in our solar system for life to have developed off Earth, given the presence of liquid water under their ice sheathes and our understanding of liquid water as one of the necessities for the development of life. Various missions are planned to these ocean worlds, but many suffer from numerous design constraints. Requirements to break through kilometers of ice on a world far from the Sun will do that to any mission. These design constraints sometimes make it difficult for the missions to achieve one of their most important functions – the search for life. But a team of engineers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory think they have a solution – send forth a swarm of swimming microbots to scour the ocean beneath a main “mothership” bot.

Continue reading “A Swarm Of Swimming Microbots Could Be Deployed To Europa’s Ocean”ESA's Juice is On Its Way to Visit Jupiter's Moons

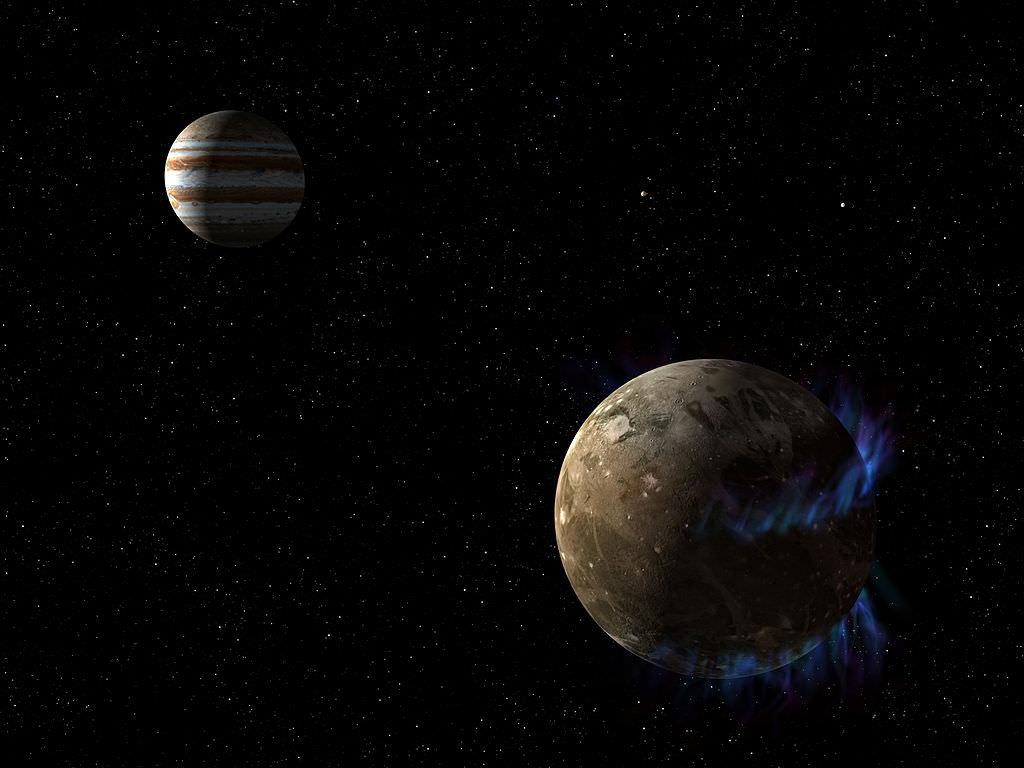

A new era of exploration at Jupiter’s moons began last week with the launch of the European Space Agency’s Juice, the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer. This mission will visit three of Jupiter’s largest moons — Europa, Callisto and Ganymede — to investigate whether they could be potentially habitable, a question that’s been highly debated since the first evidence of subsurface oceans on these moons was seen by the Galileo mission in the 1990s.

Continue reading “ESA's Juice is On Its Way to Visit Jupiter's Moons”Europa’s Ice Rotates at a Different Speed From its Interior. Now We May Know Why

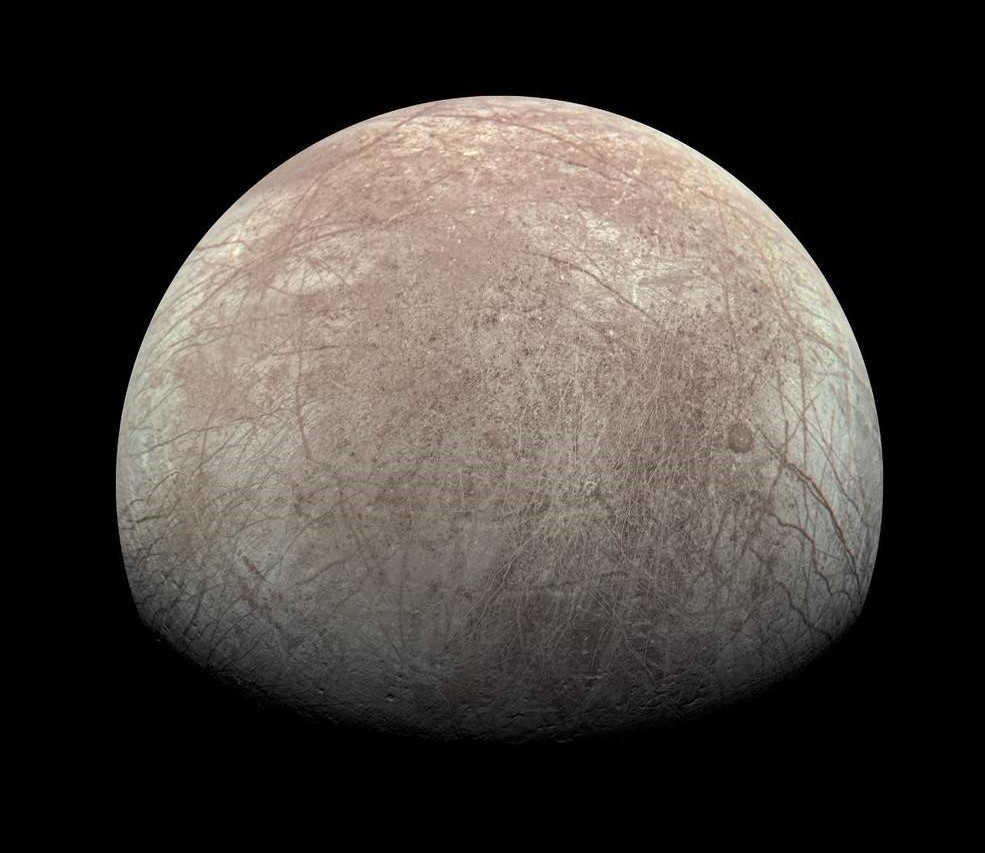

Jupiter’s moon, Europa, contains a large ocean of salty water beneath its icy shell, some of which makes it to the surface from time to time, and this vast ocean could host life, as well. Europa was most recently observed by NASA’s Juno spacecraft, but current examinations of the moon’s internal ocean are limited to computer models and simulations produced here on Earth, as no mission is actively exploring this tiny moon orbiting Jupiter. Other than the internal water occasionally breaching the icy shell and making it to the surface, what other effects could the internal ocean have on the icy shell that encloses it?

Continue reading “Europa’s Ice Rotates at a Different Speed From its Interior. Now We May Know Why”Europa Could be Covered in Salty Ice

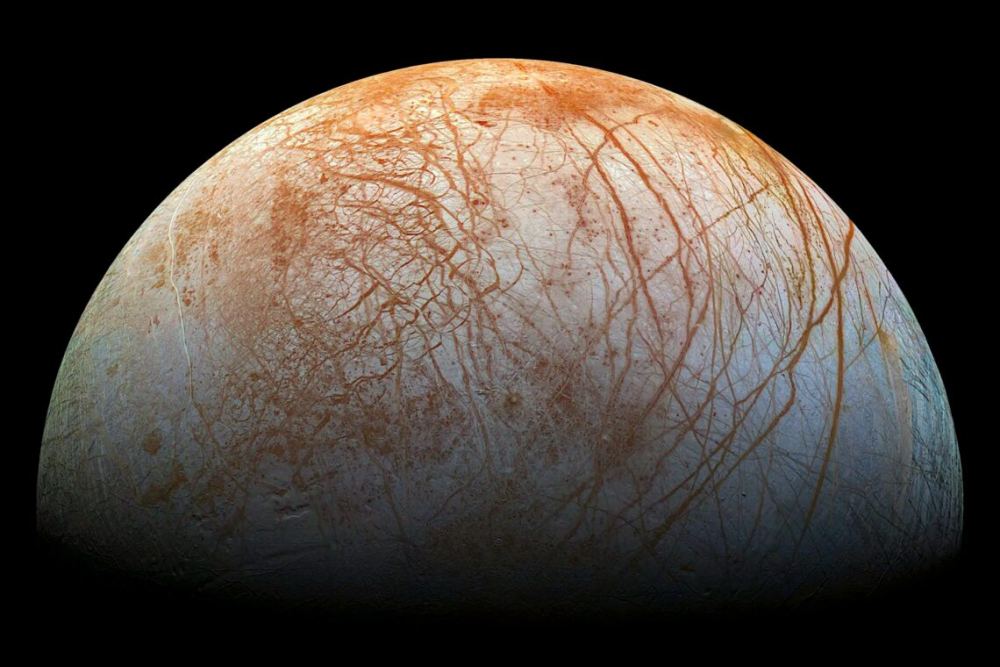

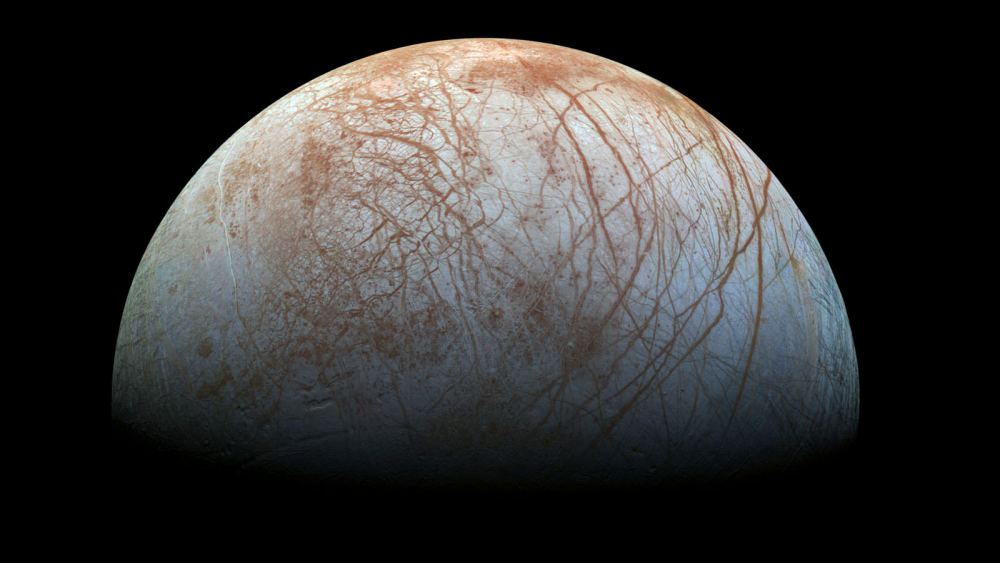

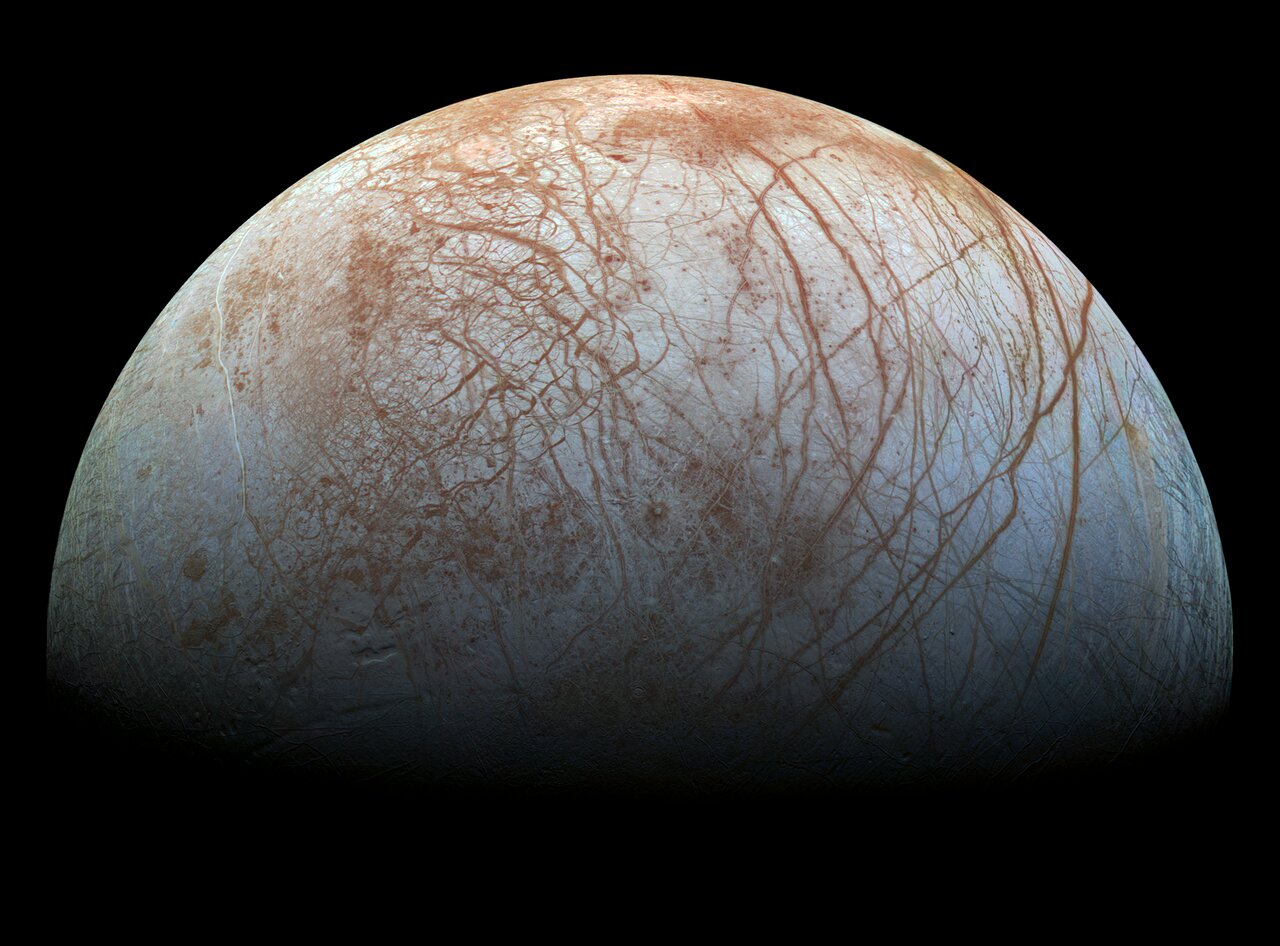

Jupiter’s second Galilean moon, Europa, is one of the most fascinating planetary objects in our Solar System with its massive subsurface ocean that’s hypothesized to contain almost three times the volume of water as the entire Earth, which opens the possibility for life to potentially exist on this small moon. But while Europa’s interior ocean could potentially be habitable for life, its unique surface features equally draw intrigue from scientists, specifically the large red streaks that crisscross its cracked surface.

Continue reading “Europa Could be Covered in Salty Ice”All of Jupiter's Large Moons Have Auroras

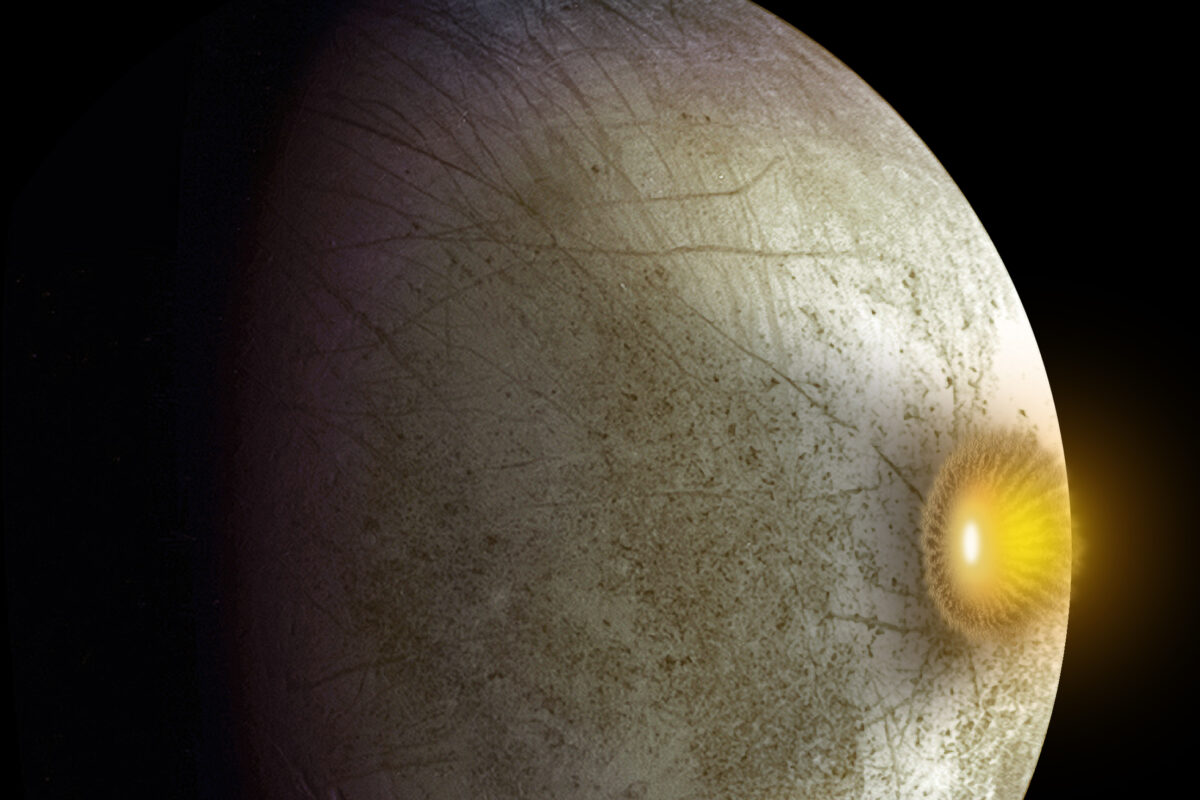

Jupiter is well known for its spectacular aurorae, thanks in no small part to the Juno orbiter and recent images taken by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Like Earth, these dazzling displays result from charged solar particles interacting with Jupiter’s magnetic field and atmosphere. Over the years, astronomers have also detected faint aurorae in the atmospheres of Jupiter’s largest moons (aka. the “Galilean Moons“). These are also the result of interaction, in this case, between Jupiter’s magnetic field and particles emanating from the moons’ atmospheres.

Detecting these faint aurorae has always been a challenge because of sunlight reflected from the moons’ surfaces completely washes out their light signatures. In a series of recent papers, a team led by the University of Boston and Caltech (with support from NASA) observed the Galilean Moons as they passed into Jupiter’s shadow. These observations revealed that Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto all experience oxygen-aurorae in their atmospheres. Moreover, these aurorae are deep red and almost 15 times brighter than the familiar green patterns we see on Earth.

Continue reading “All of Jupiter's Large Moons Have Auroras”Scientists are Simulating Europa in the Lab, Learning What They Can Before Clipper Arrives in 2030

What’s the best way to learn about Europa before we actually land a mission there? A team of scientists at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory created a mini version of this icy world in the lab. It’s giving them some fascinating insights into how that moon’s icy surface behaves and providing useful information for planners of the upcoming Europa Clipper flyby mission.

Continue reading “Scientists are Simulating Europa in the Lab, Learning What They Can Before Clipper Arrives in 2030”A Hybrid Fission/Fusion Reactor Could be the Best way to get Through the ice on Europa

In the coming years, NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) will send two robotic missions to explore Jupiter’s icy moon Europa. These are none other than NASA’s Europa Clipper and the ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE), which will launch in 2024, and 2023 (respectively). Once they arrive by the 2030s, they will study Europa’s surface with a series of flybys to determine if its interior ocean could support life. These will be the first astrobiology missions to an icy moon in the outer Solar System, collectively known as “Ocean Worlds.”

One of the many challenges for these missions is how to mine through the thick icy crusts and obtain samples from the interior ocean for analysis. According to a proposal by Dr. Theresa Benyo (a physicist and the principal investigator of the lattice confinement fusion project at NASA’s Glenn Research Center), a possible solution is to use a special reactor that relies on fission and fusion reactions. This proposal was selected for Phase I development by the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) program, which includes a $12,500 grant.

Continue reading “A Hybrid Fission/Fusion Reactor Could be the Best way to get Through the ice on Europa”Comet Impacts Could Have Brought the Raw Ingredients for Life to Europa’s Ocean

Jupiter is the most-visited planet in the Solar System, thanks largely to NASA. It all started with Pioneer 10 and 11, followed by Voyager 1 and 2. Those were all flyby missions, and it wasn’t until 1996 that the Galileo spacecraft became the first to orbit the gas giant and even send a probe into its atmosphere. Then in 2016, the Juno spacecraft entered orbit around Jupiter and is still there today.

All of these missions were focused on Jupiter, but along the way, they gave us tantalizing hints of the icy moon Europa. The most impactful thing we’ve learned is that Europa, though frozen on the surface, holds an ocean under all that ice. And that warm, salty ocean might contain more water than all of Earth’s oceans combined.

Might it hold life?

Continue reading “Comet Impacts Could Have Brought the Raw Ingredients for Life to Europa’s Ocean”If We’re Going to Get Under the Ice on Europa, How Will We Send a Signal Back to the Surface?

If we send some type of nuclear-powered tunnelbot to Europa to seek life under its icy shield, how will we know what it finds? How can a probe immersed in water under all that ice communicate with Earth? We only have hints about the nature of that ice, what layers it has and what pockets of water it might hold.

All we know is that it’s tens of kilometres thick and as hard as granite.

Continue reading “If We’re Going to Get Under the Ice on Europa, How Will We Send a Signal Back to the Surface?”