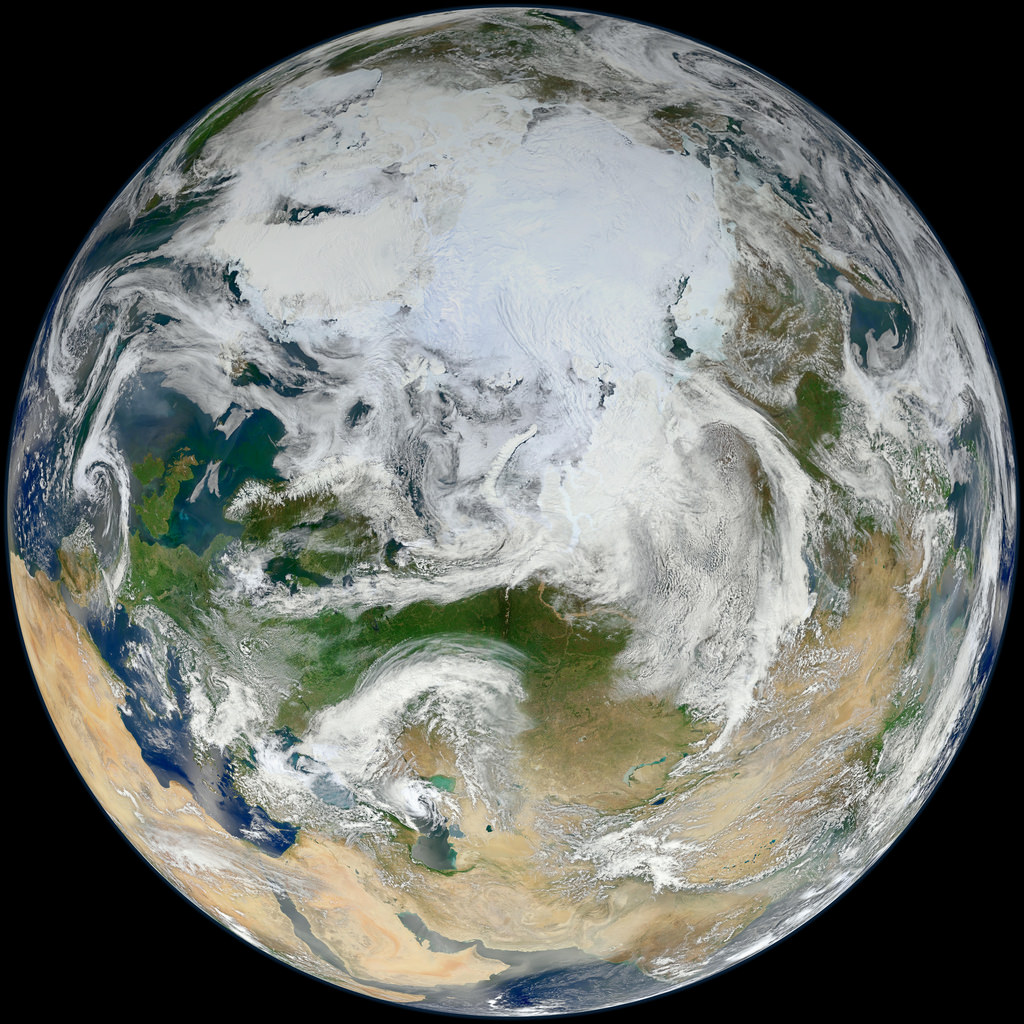

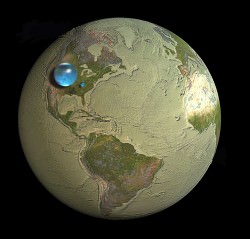

Water, water everywhere… Coleridge’s shipbound ancient mariners were plagued by a lack of water while surrounded by a sea of the stuff, and while 70% of Earth’s surface is indeed covered by water (of which 96% is salt water, hence not a drop to drink) there’s really not all that much — not when compared to the entire mass of the planet. Less than 1% of Earth is water, which seems odd to scientists because, based on conventional models of how the Solar System formed, there should have been a lot more water available in Earth’s neck of the woods when it was coming together. So the question has been floating around: why is Earth so dry?

According to a new study from the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, MD, the answer may lie in the snow.

The snow line, to be exact. The region within a planetary system beyond which temperatures are cold enough for water ice to exist, the snow line in our solar system is currently located in the middle of the main asteroid belt, between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. Based on conventional models of how the Solar System developed, this boundary used to be closer in to the Sun, 4.5 billion years ago. But if that were indeed the case, then Earth should have accumulated much more ice (and therefore water) as it was forming, becoming a true “water world” with a water mass up to 40 percent… instead of a mere one.

As we can see today, that wasn’t the case.

As we can see today, that wasn’t the case.

“Planets such as Uranus and Neptune that formed beyond the snow line are composed of tens of percents of water. But Earth doesn’t have much water, and that has always been a puzzle.”

– Rebecca Martin, Space Telescope Science Institute

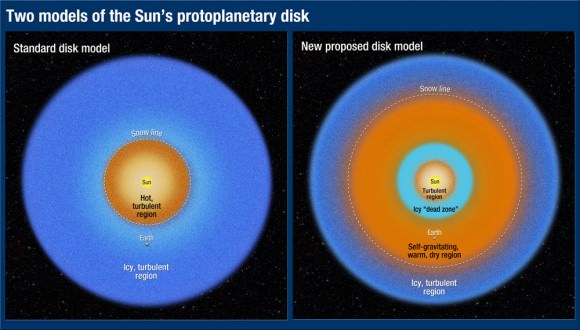

A study led astrophysicists Rebecca Martin and Mario Livio of the Space Telescope Science Institute took another look at how the snow line in our solar system must have evolved, and found that, in their models, Earth was never inside the line. Instead it stayed within a warmer, drier region inside of the snow line, and away from the ice.

“Unlike the standard accretion-disk model, the snow line in our analysis never migrates inside Earth’s orbit,” Livio said. “Instead, it remains farther from the Sun than the orbit of Earth, which explains why our Earth is a dry planet. In fact, our model predicts that the other innermost planets, Mercury, Venus, and Mars, are also relatively dry. ”

Read: Rethinking the Source of Earth’s Water

The standard model states that in the early days of a protoplanetary disk’s formation ionized material within it gradually falls toward the star, drawing the icy, turbulent snow line region inward. But this model depends upon the energy of an extremely hot star fully ionizing the disk — energy that a young star, like our Sun was, just didn’t have.

“We said, wait a second, disks around young stars are not fully ionized,” Livio said. “They’re not standard disks because there just isn’t enough heat and radiation to ionize the disk.”

“Astrophysicists have known for quite a while that disks around young stellar objects are NOT standard accretion disks (namely, ones that are ionized and turbulent throughout),” added Dr. Livio in an email to Universe Today. “Disk models with dead zones have been constructed by many people for many years. For some reason, however, calculations of the evolution of the snow line largely continued to use the standard disk models.”

Without fully ionized disk, the material is not drawn inward. Instead it orbits the star, condensing gas and dust into a “dead zone” that blocks outlying material from coming any closer. Gravity compresses the dead zone material, which heats up and dries out any ices that exist immediately outside of it. Based on the team’s research it was in this dry region that Earth formed.

The rest, as they say, is water under the bridge.

The team’s results have been accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Read the release on the Hubble news site here, and see the full paper here.

Lead image: Earth as seen by MESSENGER spacecraft before it left for Mercury in 2004. NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington. Disk model image: NASA, ESA, and A. Feild (STScI). Earth water volume image: Howard Perlman, USGS; globe illustration by Jack Cook, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (©); Adam Nieman.