[/caption]

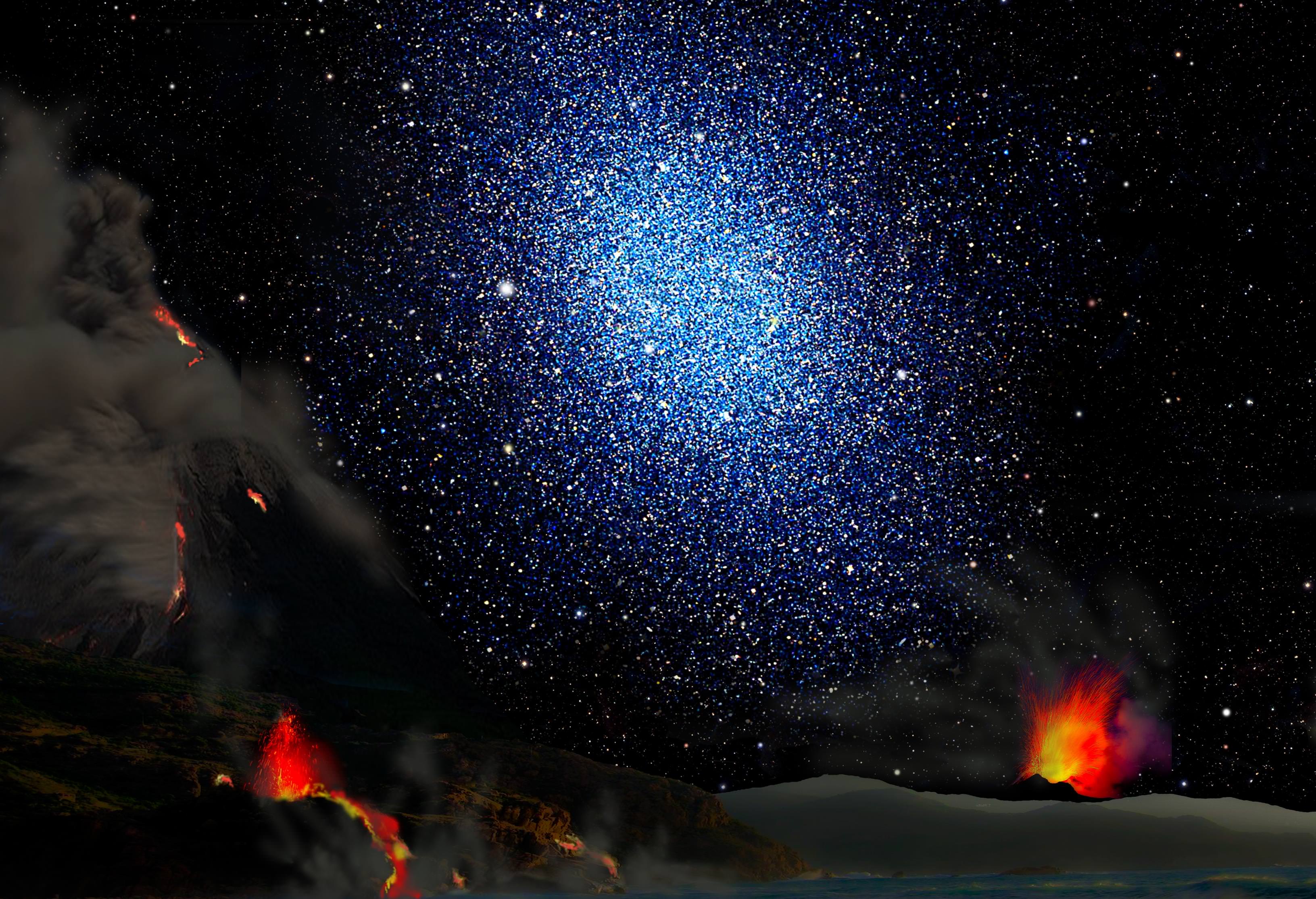

Away in space some 4.57 billion years ago, in a galaxy yet to be called the Milky Way, a hydrogen molecular cloud collapsed. From it was born a G-type main sequence star and around it swirled a solar nebula which eventually gelled into a solar system. But just what caused the collapse of the molecular cloud? Astronomers have theorized it may have been triggered by a nearby supernova event… And now new computer modeling confirms that our Solar System was born from the ashes a dead star.

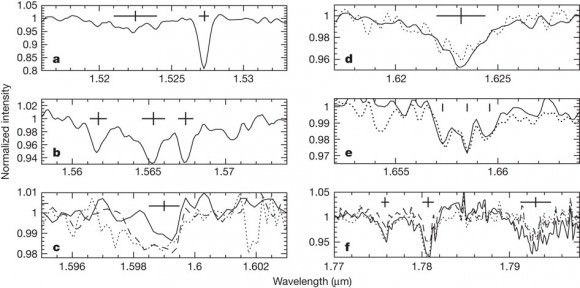

While this may seem like a cold case file, there are still some very active clues – one of which is the study of isoptopes contained within the structure of meteorites. As we are well aware, many meteorites could very well be bits of our primordial solar nebula, left virtually untouched since they formed. This means their isotopic signature could spell out the conditions that existed within the molecular cloud at the time of its collapse. One strong factor in this composition is the amount of aluminium-26 – an element with a radioactive half-life of 700,000 years. In effect, this means it only takes a relatively minor period of time for the ratio between Al-26 and Al-24 to change.

“The time-scale for the formation events of our Solar System can be derived from the decay products of radioactive elements found in meteorites. Short lived radionuclides (SLRs) such as 26Al , 41Ca, 53Mn and 60Fe can be employed as high-precision and high-resolution chronometers due to their short half-lives.” says M. Gritschneder (et al). “These SLRs are found in a wide variety of Solar System materials, including calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions (CAIs) in primitive chondrites.”

However, it would seem that a class of carbonaceous chondrite meteorites known CV-chondrites, have a bit more than their fair share of Al-26 in their structure. Is it the smoking gun of an event which may have enriched the cloud that formed it? Isotope measurements are also indicative of time – and here we have two examples of meteorites which formed within 20,000 years of each other – yet are significantly different. What could have caused the abundance of Al-26 and caused fast formation?

“The general picture we adopt here is that a certain amount of Al-26 is injected in the nascent solar nebula and then gets incorporated into the earliest formed CAIs as soon as the temperature drops below the condensation temperature of CAI minerals. Therefore, the CAIs found in chondrites represent the first known solid objects that crystalized within our Solar System and can be used as an anchor point to determine the formation time-scale of our Solar System.” explains Gritschneder. “The extremely small time-span together with the highly homogeneous mixing of isotopes poses a severe challenge for theoretical models on the formation of our Solar System. Various theoretical scenarios for the formation of the Solar System have been discussed. Shortly after the discovery of SLRs, it was proposed that they were injected by a nearby massive star. This can happen either via a supernova explosion or by the strong winds of a Wolf-Rayet star.”

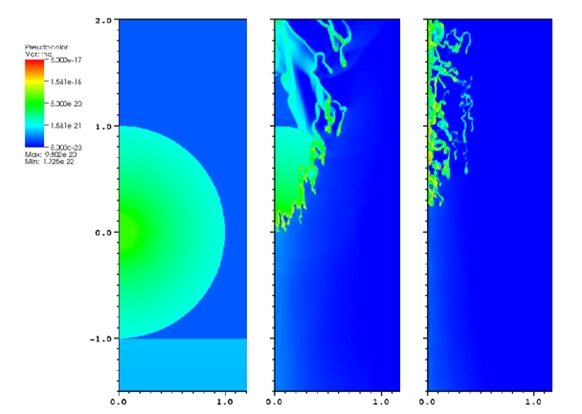

While these two theories are great, only one problem remains… Distinguishing the difference between the two events. So Matthias Gritschneder of Peking University in Beijing and his colleagues set to work designing a computer simulation. Biased towards the supernova event, the model demonstrates what happens when a shockwave encounters a molecular cloud. The results are an appropriate proportion of Al-26 – and a resultant solar system formation.

“After discussing various scenarios including X-winds, AGB stars and Wolf-Rayet stars, we come to the conclusion that triggering the collapse of a cold cloud core by a nearby supernova is the most promising scenario. We then narrow down the vast parameter space by considering the pre-explosion survivability of such a clump as well as the cross-section necessary for sufficient enrichment.” says Gritschneder. “We employ numerical simulations to address the mixing of the radioactively enriched SN gas with the pre-existing gas and the forced collapse within 20 kyr. We show that a cold clump at a distance of 5 pc can be sufficiently enriched in Al-26 and triggered into collapse fast enough – within 18 kyr after encountering the supernova shock – for a range of different metallicities and progenitor masses, even if the enriched material is assumed to be distributed homogeneously in the entire supernova bubble. In summary, we show that the triggered collapse and formation of the Solar System as well as the required enrichment with radioactive 26Al are possible in this scenario.”

While there are still other isotope ratios yet to be explained and further modeling done, it’s a step toward the future understanding of how solar systems form.

Original Story Source: MIT Technology Review News Release. For Further Reading: The Supernova Triggered Formation And Enrichment Of Our Solar System.