[/caption]

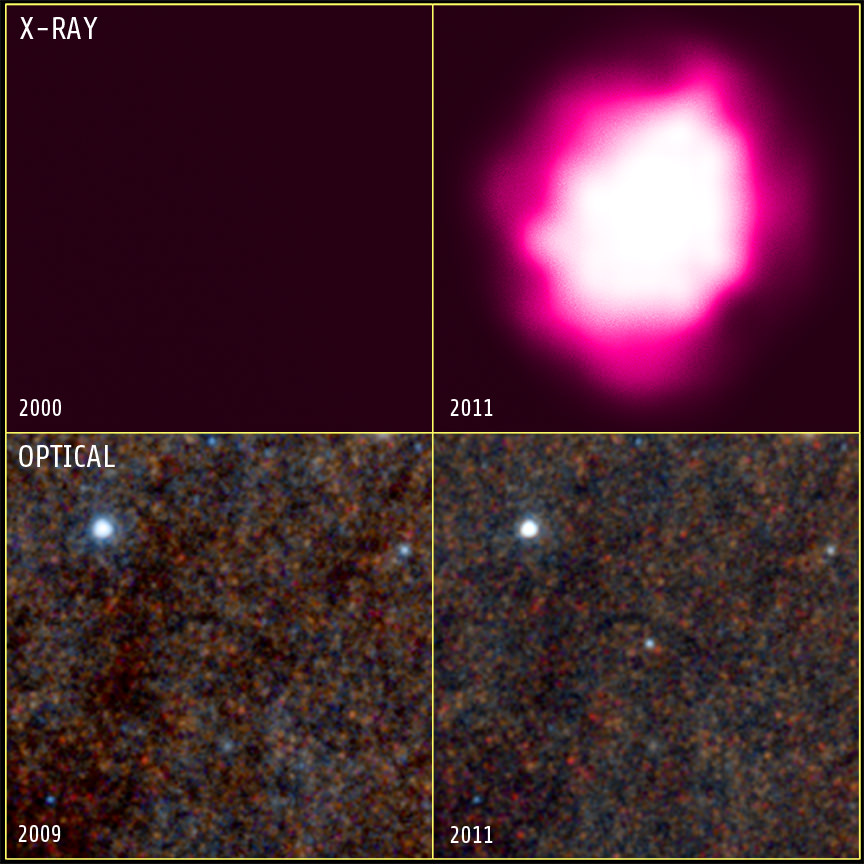

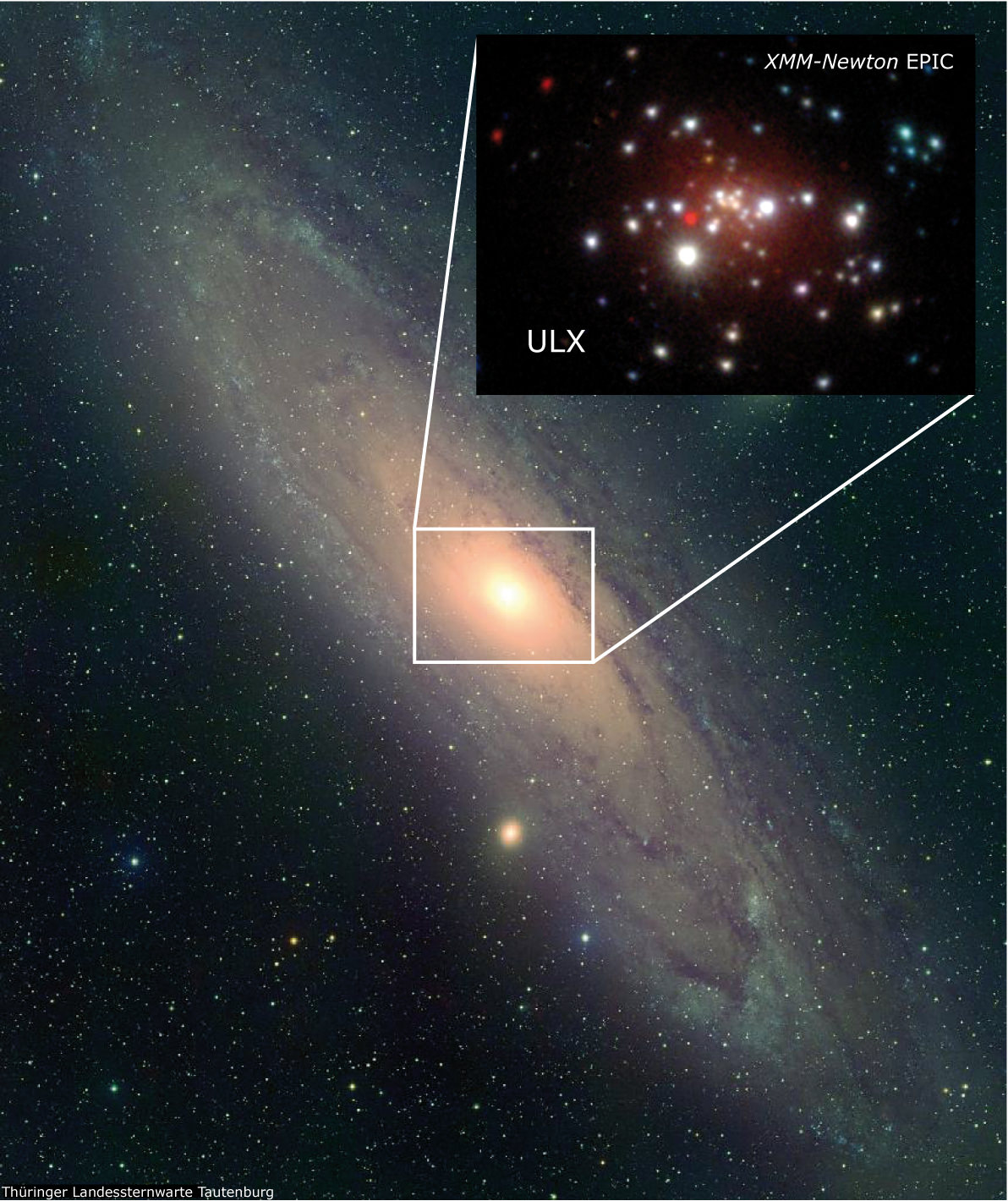

Astronomers keeping an eye out for a supernova explosion in the nearby galaxy M83 instead witnessed a prodigious blast of another type: a new ultraluminous X-ray source, or ULX. In what scientists are calling an “extraordinary outburst,” the ULX in M83 increased in X-ray brightness by at least 3,000 times, one of the largest changes in X-rays ever seen for this type of object.

“The flaring up of this ULX took us by surprise and was a sure sign we had discovered something new about the way black holes grow,” said Roberto Soria of Curtin University in Australia, who led the new study.

The researchers say this blast provides direct evidence for a population of old, volatile stellar black holes and gives new insight into the nature of a mysterious class of black holes that can produce as much energy in X-rays as a million suns radiate at all wavelengths.

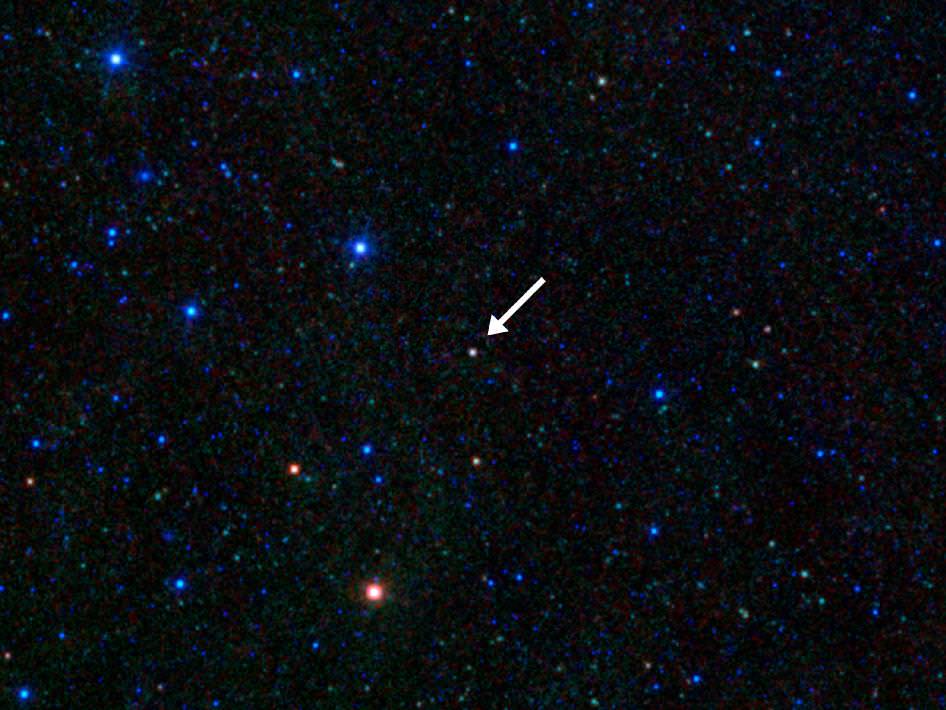

Astrophysicist Bill Blair of Johns Hopkins University, writing in the Chandra Blog, “A Funny Thing Happened While Waiting for the Next Supernova in M83,” said this galaxy, also known as the Southern Pinwheel Galaxy, “is an amazing gift of nature. At 15 million light years away, it is actually one of the closer galaxies (only 7-8 times more distant than the Andromeda galaxy), but it appears as almost exactly face-on, giving earthlings a fantastic view of its beautiful spiral arms and active star-forming nucleus.”

M83 has generated six observed supernovas since 1923, but the last one seen was in 1983. “We are overdue for a new supernova!” Blair wrote.

So, many astronomers have been observing M83, hoping to spot a new supernova, but instead saw a dramatic jump in X-ray brightness, which according to the researchers, likely occurred because of a sudden increase in the amount of material falling into the black hole.

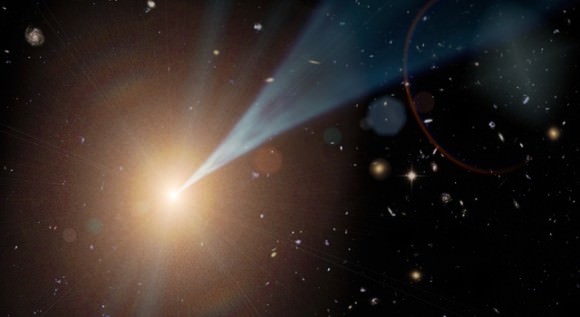

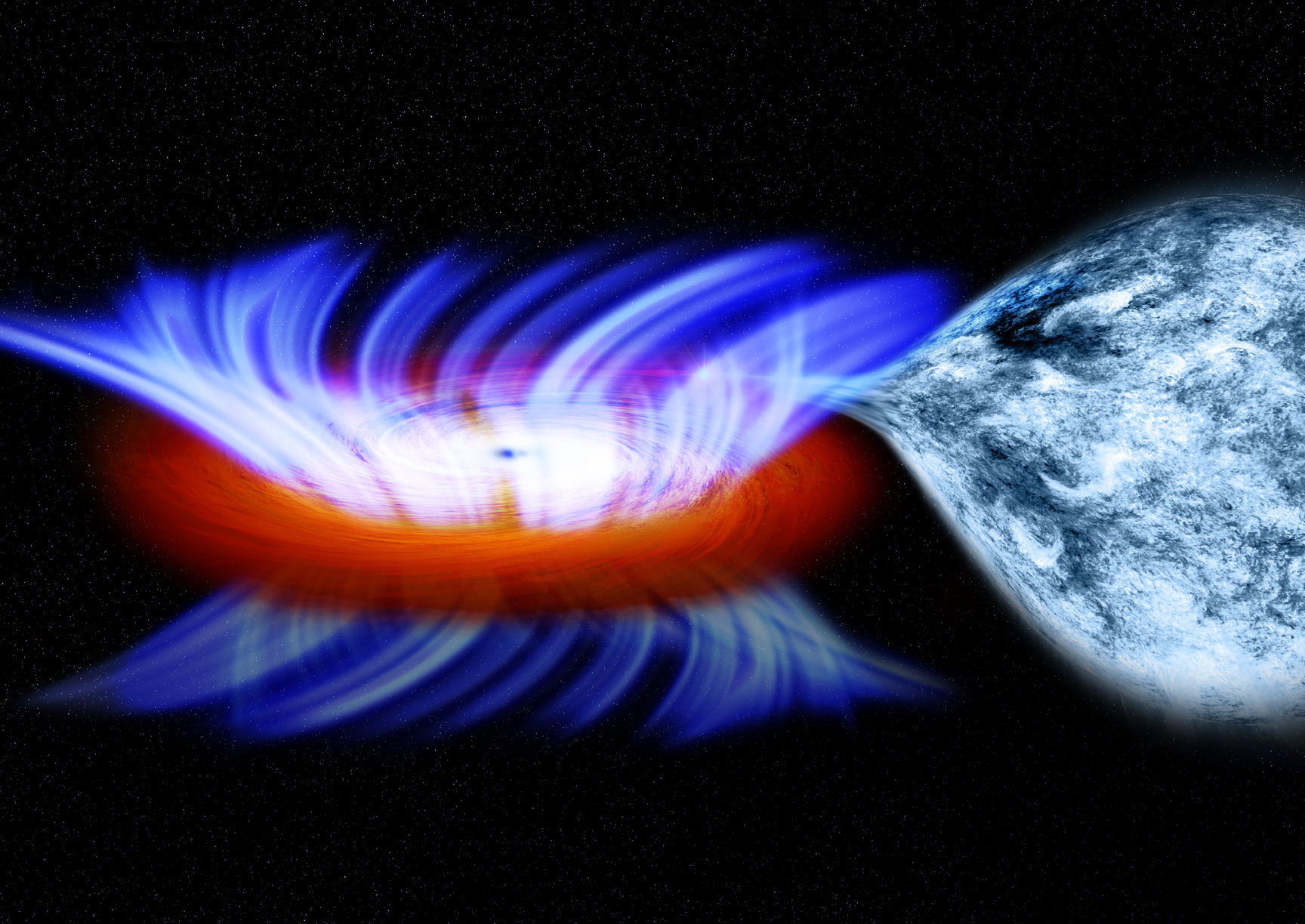

A ULX can give off more X-rays than most “normal” binary systems in which a companion star is in orbit around a neutron star or black hole. The super-sized X-ray emission suggests ULXs contain black holes that might be much more massive than the ones found elsewhere in our galaxy.

The companion stars to ULXs, when identified, are usually young, massive stars, implying their black holes are also young. The latest research, however, provides direct evidence that ULXs can contain much older black holes and some sources may have been misidentified as young ones.

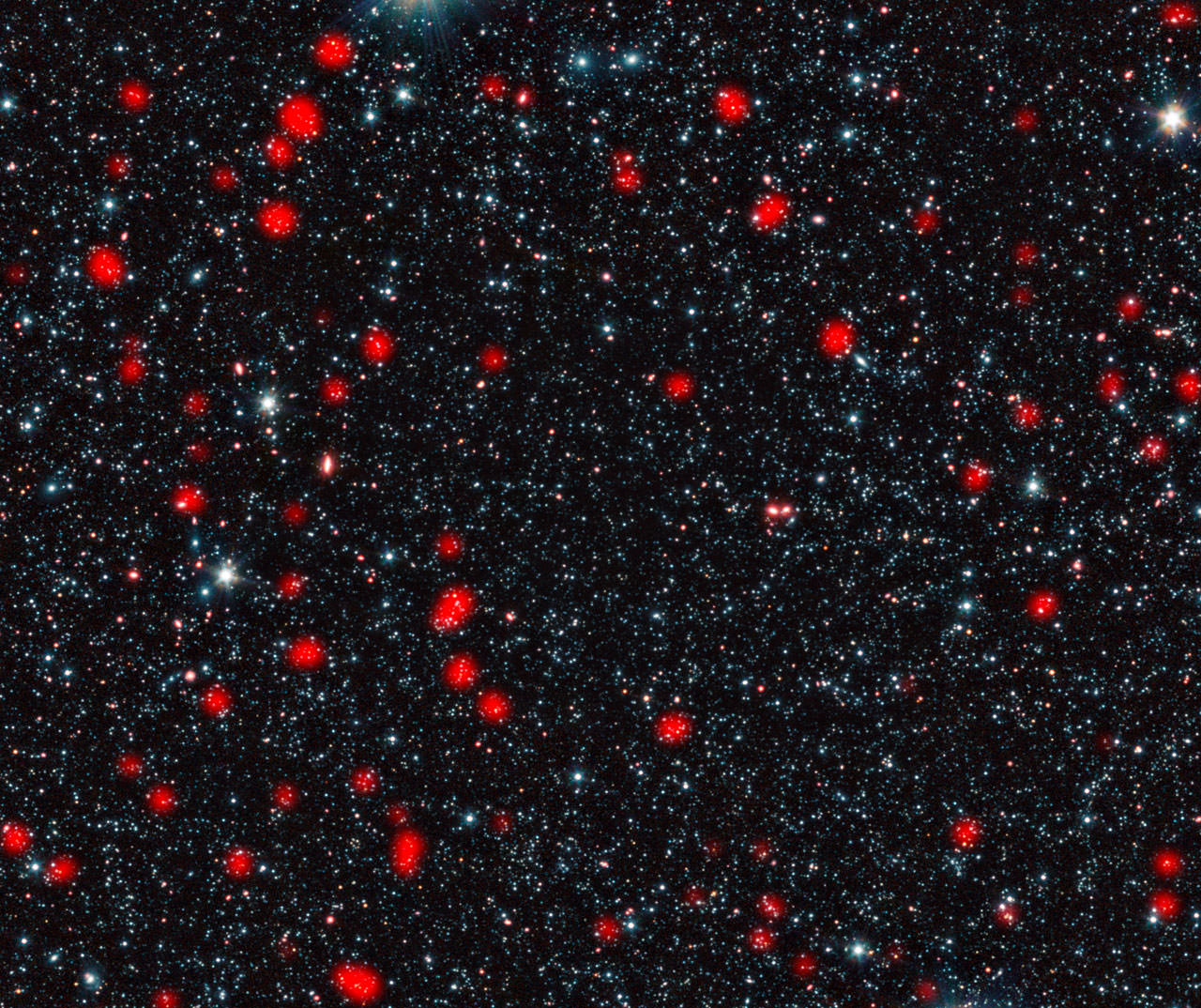

The observations of M83 were made over a several year period with Chandra. No sign of the ULX was found in historical X-ray images made with Einstein Observatory in 1980, ROSAT in 1994, the European Space Agency’s XMM-Newton in 2003 and 2008, NASA’s Swift observatory in 2005, the Magellan Telescope observations in April 2009 or in a Hubble image obtained in August 2009.

But in 2011, Soria and his colleagues used optical images from the Gemini Observatory and NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and saw a bright blue source at the position of the X-ray source.

The lack of a blue source in the earlier images indicates the black hole’s companion star is fainter, redder and has a much lower mass than most of the companions that previously have been directly linked to ULXs. The bright, blue optical emission seen in 2011 must have been caused by a dramatic accumulation of more material from the companion star.

“If the ULX only had been observed during its peak of X-ray emission in 2010, the system easily could have been mistaken for a black hole with a massive, much younger stellar companion, about 10 to 20 million years old,” said co-author Blair.

The companion to the black hole in M83 is likely a red giant star at least 500 million years old, with a mass less than four times the sun’s. Theoretical models for the evolution of stars suggest the black hole should be almost as old as its companion.

Another ULX containing a volatile, old black hole recently was discovered in the Andromeda galaxy by a team led by Amanpreet Kaur from Clemson University, published in the February 2012 issue of Astronomy and Astrophysics. Matthew Middleton and colleagues from the University of Durham reported more information in the March 2012 issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. They used data from Chandra, XMM-Newton and HST to show the ULX is highly variable and its companion is an old, red star.

“With these two objects, it’s becoming clear there are two classes of ULX, one containing young, persistently growing black holes and the other containing old black holes that grow erratically,” said Kip Kuntz, a co-author of the new M83 paper, also of Johns Hopkins University. “We were very fortunate to observe the M83 object at just the right time to make the before and after comparison.”

A paper describing these results will appear in the May 10th issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

Sources: NASA, Chandra Blog