Current theories may not describe our Universe very accurately. Image credit: Brussels Museum of Fine Arts, and Space Telescope Institute. Click to enlarge

A Chinese astronomer from the University of St Andrews has fine-tuned Einstein’s groundbreaking theory of gravity, creating a ‘simple’ theory which could solve a dark mystery that has baffled astrophysicists for three-quarters of a century.

A new law for gravity, developed by Dr Hong Sheng Zhao and his Belgian collaborator Dr Benoit Famaey of the Free University of Brussels (ULB), aims to prove whether Einstein’s theory was in fact correct and whether the astronomical mystery of Dark Matter actually exists. Their research was published on February 10th in the US-based Astrophysical Journal Letters. Their formula suggests that gravity drops less sharply with distance as in Einstein, and changes subtly from solar systems to galaxies and to the universe.

Theories of the physics of gravity were first developed by Isaac Newton in 1687 and refined by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity in 1905 to allow light bending. While it is the earliest-known force, gravity is still very much a mystery with theories still unconfirmed by astronomical observations in space.

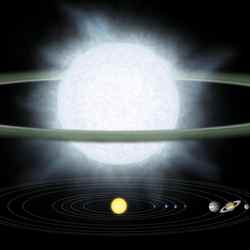

The ‘problem’ with the golden laws of Newton and Einstein is whilst they work very well on earth, they do not explain the motion of stars in galaxies and the bending of light accurately. In galaxies, stars rotate rapidly about a central point, held in orbit by the gravitational attraction of the matter in the galaxy. However astronomers found that they were moving too quickly to be held by their mutual gravity – so not enough gravity to hold the galaxies together instead stars should be thrown off in all directions!

The solution to this, proposed by Fritz Zwicky in 1933, was that there was unseen material in the galaxies, making up enough gravity to hold the galaxies together. As this material emits no light astronomers call it ‘Dark Matter’. It is thought to account for up to 90% of matter in the Universe. Not all scientists accept the Dark Matter theory however. A rival solution was proposed by Moti Milgrom in 1983 and backed up by Jacob Bekenstein in 2004. Instead of the existence of unseen material, Milgrom proposed that astronomers understanding of gravity was incorrect. He proposed that a boost in the gravity of ordinary matter is the cause of this acceleration.

Milgrom’s theory has been worked on by a number of astronomers since and Dr Zhao and Dr Famaey have proposed a new formulation of his work that overcomes many of the problems previous versions have faced.

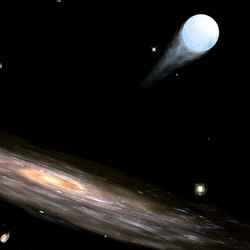

They have created a formula that allows gravity to change continuously over various distance scales and, most importantly, fits the data for observations of galaxies. To fit galaxy data equally well in the rival Dark Matter paradigm would be as challenging as balancing a ball on a needle, which motivated the two astronomers to look at an alternative gravity idea.

Legend has it that Newton began thinking about gravity when an apple fell on his head, but according to Dr Zhao, “It is not obvious how an apple would fall in a galaxy. Mr Newton’s theory would be off by a large margin – his apple would fly out of the Milky Way. Efforts to restore the apple on a nice orbit around the galaxy have over the years led to two schools of thoughts: Dark Matter versus non-Newtonian gravity. Dark Matter particles come naturally from physics, with beautiful symmetries and explain cosmology beautifully; they tend to be everywhere. The real mystery is how to keep them away from some corners of the universe. Also Dark Matter comes hand- in-hand with Dark Energy. It would be more beautiful if there were one simple answer to all these mysteries”.

Dr Zhao, a PPARC Advanced Fellow at University of St Andrews, School of Physics and Astronomy, and member of the Scottish Universities Physics Alliance (SUPA), continued “There has always been a fair chance that astronomers might rewrite the law of gravity. We have created a new formula for gravity which we call ‘the simple formula’, and which is actually a refinement of Milgrom’s and Bekenstein’s. It is consistent with galaxy data so far, and if its predictions are further verified for solar system and cosmology, it could solve the Dark Matter mystery. We may be able to answer common questions such as whether Einstein’s theory of gravity is right and whether the so-called Dark Matter actually exists”.

“A non-Newtonian gravity theory is now fully specified on all scales by a smooth continuous function. It is ready for fellow scientists to falsify. It is time to keep an open mind for new fields predicted in our formula while we continue our search for Dark Matter particles.”

The new formula will be presented to an international workshop at Edinburgh’s Royal Observatory in April, which will be given the opportunity to test and debate the reworked theory. Dr Zhao and Dr Famaey will demonstrate their new formula to an audience of Dark Matter and gravity experts from ten different countries.

Dr Famaey commented “It is possible that neither the modified gravity theory, nor the Dark Matter theory, as they are formulated today, will solve all the problems of galactic dynamics or cosmology. The truth could in principle lie in between, but it is very plausible that we are missing something fundamental about gravity, and that a radically new theoretical approach will be needed to solve all these problems. Nevertheless, our formula is so attractively simple that it is tempting to see it as part of a yet unknown fundamental theory. All galaxy data seem to be explained effortlessly”.

Original Source: PPARC News Release