There’s an often told anecdote that astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus never spied Mercury. And while this tale is almost certainly apocryphal, it does speak to just how elusive the innermost planet of our solar system really is.

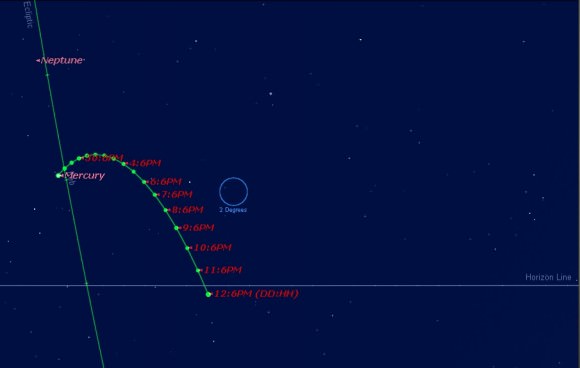

Never seen Mercury for yourself? This final week of January offers a good time to try, as Mercury reaches greatest elongation east of the Sun on Friday, January 31st.

This will offer northern hemisphere viewers one on the best chances to spot the fleeting world low to the west immediately after local sunset. And although we get on average six apparitions of Mercury per year – three each in the dawn and dusk – all apparitions aren’t created equal.

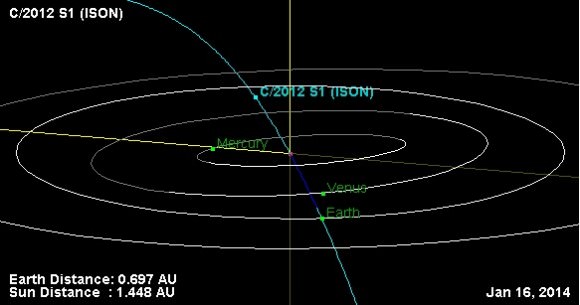

The approximate moment of greatest elongation occurs on January 31st at 10:00 UT / 5:00 AM EST, when Mercury is 18.4 degrees east of the Sun. This is only 0.5 degrees shy of the smallest elongation for Mercury that can occur, as the planet reaches perihelion just three days later on February 3rd at 0.3075 Astronomical Units (AUs) from the Sun. The last time this was surpassed was the evening elongation of February 16th, 2013th, and the next time it’ll be topped is October 16th, 2015 at just 18.1 degrees from the Sun.

And though this elongation is closer than usual, this also works in the Mercury-spotter’s favor. At greatest elongation, Mercury will present a 50% illuminated 7 arc second disk, readily apparent in a small telescope. But a also means that Mercury will appear almost a full magnitude brighter than it does when it reaches greatest elongation near aphelion, as it last did on March 31st of last year, and will do again on March 14th of this year.

Mercury will shine at magnitude -0.4 low towards the west into this coming weekend. We managed to pick up Mercury with binoculars on January 16th and have since managed to start tracking the planet unaided since January 18th.

Mercury also has another factor going for it, in terms of the angle of the evening ecliptic. Following ahead of the Sun, Mercury occupies a space that the Sun will trace up its apparent path along the ecliptic as it begins its long slow crawl northward towards the Vernal Equinox on March 20th. This means that Mercury is almost perpendicular above the western horizon at dusk and is currently getting a maximum boost above the atmospheric murk.

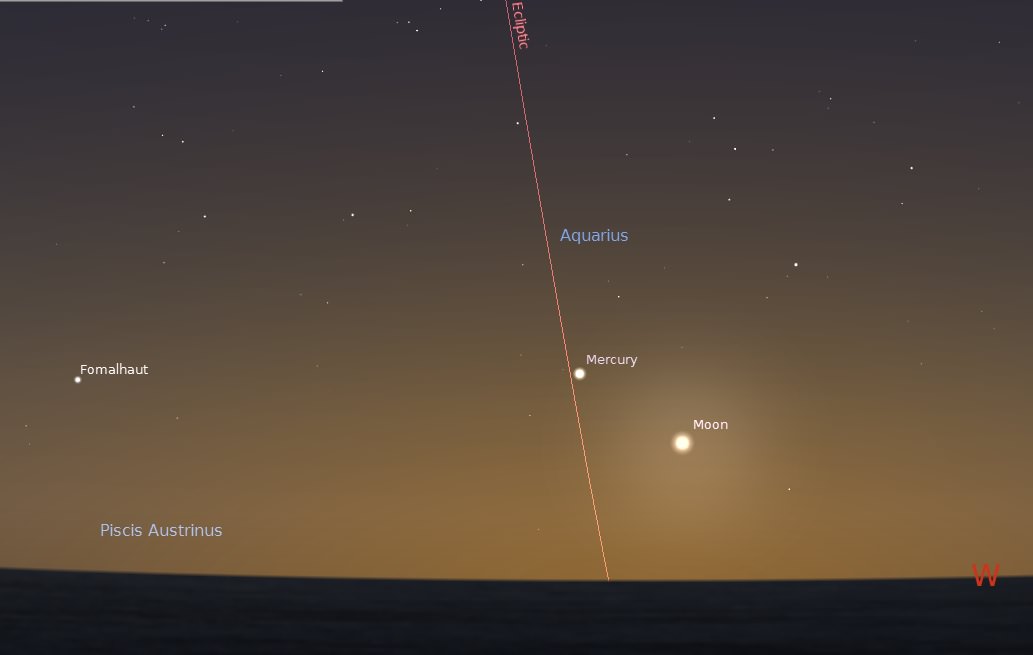

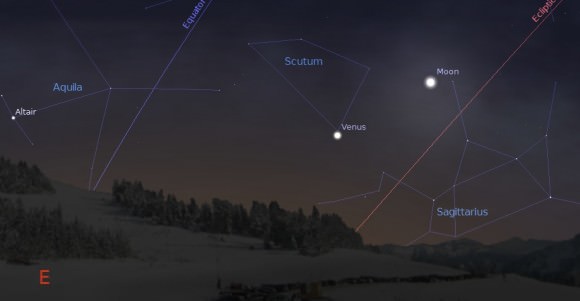

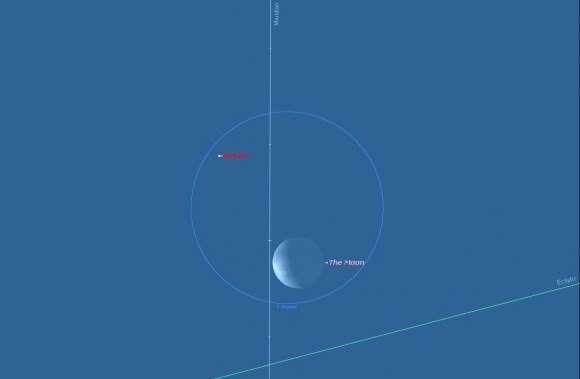

Mercury also gets joined by a razor thin waxing crescent Moon just over 24 hours past New sliding by it on the evening of Friday, January 31st. Look for the Moon five degrees to the right of Mercury on the 31st. The Moon will be a much easier catch on the February 1st when its 10 degrees above Mercury. And can you spy the +1 magnitude star Fomalhaut in the constellation Piscis Austrinus just 20 degrees to the south of Mercury?

And speaking of the Moon, this week’s New Moon is the second of the month, a feat that repeats in March 2014 and leaves the month of February “New Moon-less…” such an occurrence in either instance is informally known as a Black Moon.

Orbiting the Sun once every 88 days, Mercury completes about 4.15 circuits of the Sun for every Earth year. From our Earthbound vantage point, however, Mercury seems to only orbit the Sun 3.15 times a year. Thus 6 elongations (3 in the dusk and 3 in the dawn) will occur every year, through 7 can occur, as last happened in 2011 and will occur again next year in 2015.

After this weekend, Mercury will resume its plunge towards the horizon through early February. Mercury will begin retrograde (westward) apparent motion against the starry background on February 6th before resuming direct (eastward motion) on February 27th. And although astrologers may find that “Mercury in retrograde” is a convenient “blame magnet,” they’re also falling prey to a logical fallacy known as retrofitting, as Mercury spends a longer fraction of time than any other planet “in retrograde” at about 20%!

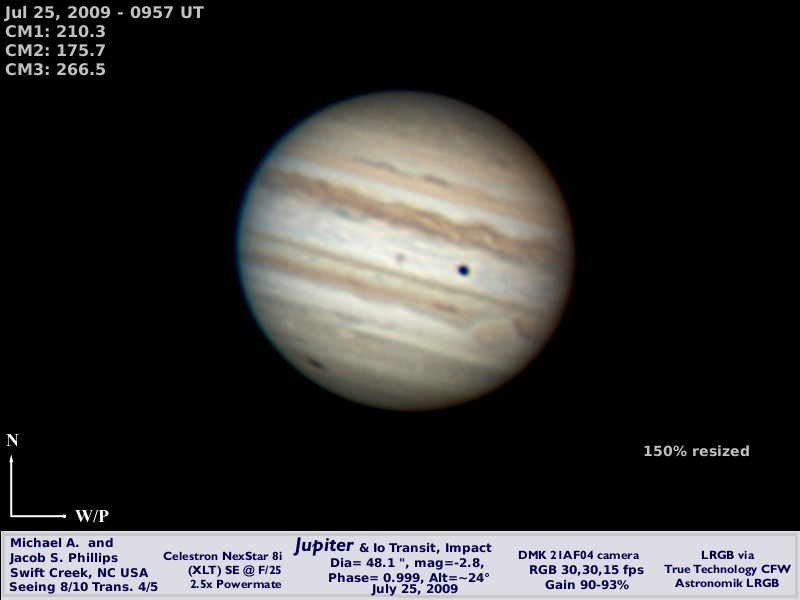

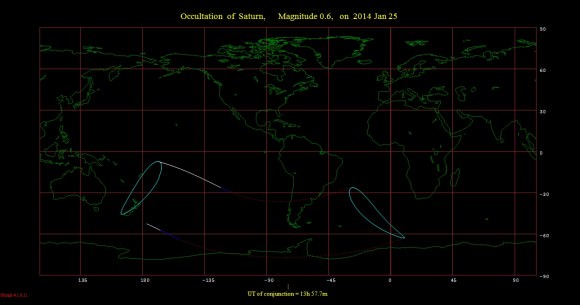

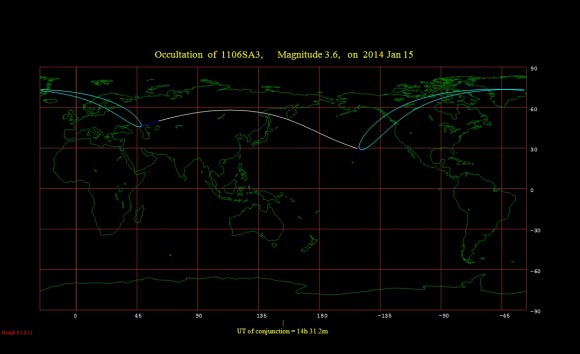

From there, Mercury heads towards inferior conjunction between the Earth and the Sun on Saturday, February 15th, passing just 3.7 degrees north of the solar disk. You can catch Mercury entering into the field of view of the Solar Heliospheric Observatory’s (SOHO) LASCO C3 camera from February 12th to February 18th.

And although Mercury misses this time, we’re not that far away from the next transit of Mercury across the face of the Sun on May 9th, 2016.

Up for more? An even tougher challenge is to attempt to spot Mercury… in the daytime. We’ve noted this possibility before as Mercury reaches maximum elongation from the Sun while still in the negative magnitude range. Of course, you want to physically block the Sun out of view, and don’t even try sweeping the sky near the Sun visually with binoculars or a telescope! You’ll need a clear, blue sky for maximum contrast and a polarizing filter may help in your quest… but this should be possible under exceptional conditions.

Good luck, and be sure to send those Mercury pics in to Universe Today!