They’re nearby, they’re common and — at least in the latest exoplanet newsflashes hot off the cyber-press — they’re hot. We’re talking about red dwarf stars, those “salt of the galaxy” stars that litter the Milky Way. And while it’s true that there are more of “them” than there are of “us,” not a single one is bright enough to be seen with the naked eye from the skies of Earth.

A reader recently brought up an engaging discussion of what red dwarfs might be within reach of a backyard telescope, and thus this handy compilation was born.

Of course, red dwarfs are big news as possible hosts for life-bearing planets. Though the habitable zones around these stars would be very close in, these miserly stars will shine for trillions of years, giving evolution plenty of opportunity to do its thing. These stars are, however, tempestuous in nature, throwing out potentially planet sterilizing flares.

Red dwarf stars range from about 7.5% the mass of our Sun up to 50%. Our Sun is very nearly equivalent 1000 Jupiters in mass, thus the range of red dwarf stars runs right about from 75 to 500 Jupiter masses.

For this list, we considered red dwarf stars brighter than +10th magnitude, with the single exception of 40 Eridani C as noted.

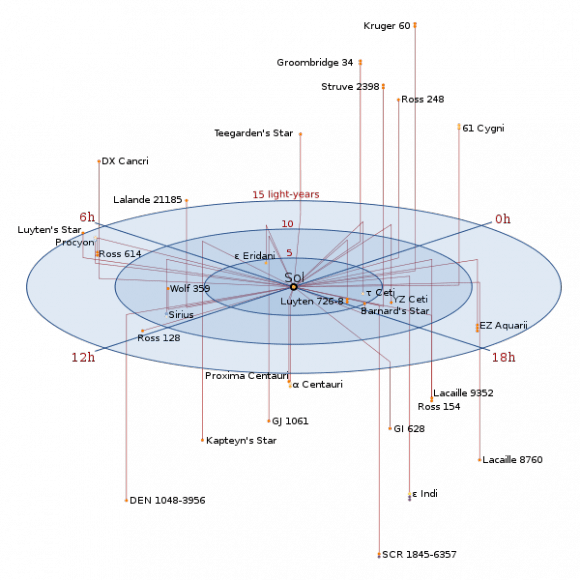

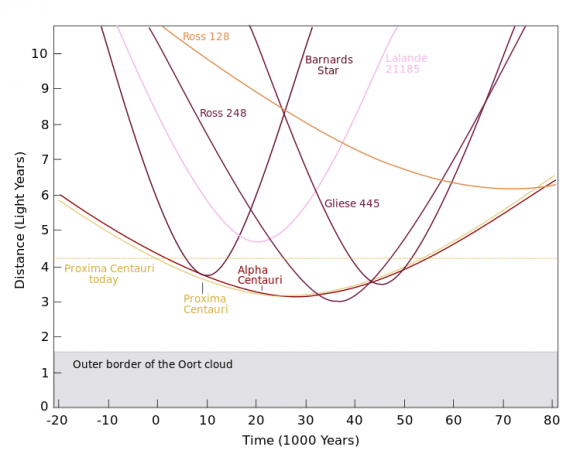

I know what you’re thinking… what about the closest? At magnitude +11, Proxima Centauri in the Alpha Centauri triple star system 4.7 light years distant didn’t quite make the cut. Barnard’s Star (see below) is the closest in this regard. Interestingly, the brown dwarf pair Luhman 16 was discovered just last year at 6.6 light years distant.

Also, do not confuse red dwarfs with massive carbon stars. In fact, red dwarfs actually appear to have more of an orange hue visually! Still, with the wealth of artist’s conceptions (see above) out there, we’re probably stuck with the idea of crimson looking red dwarf stars for some time to come.

| Star | Magnitude | Constellation | R.A. | Dec |

| Groombridge 34 | +8/11(v) | Andromeda | 00h 18’ | +44 01’ |

| 40 Eridani C | +11 | Eridanus | 04h 15’ | -07 39’ |

| AX Microscopii/Lacaille 8760 | +6.7 | Microscopium | 21h 17’ | -38 52’ |

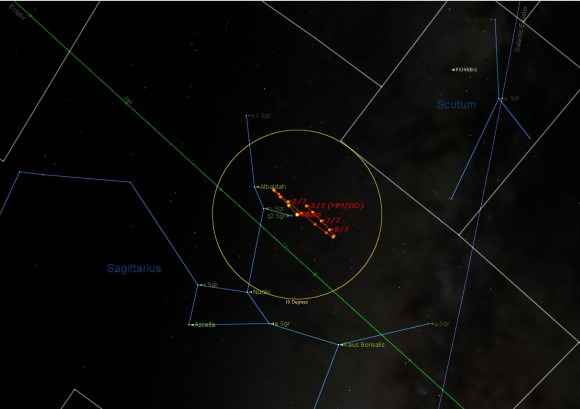

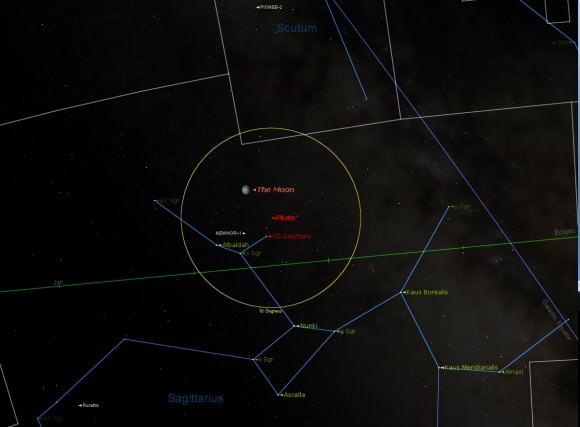

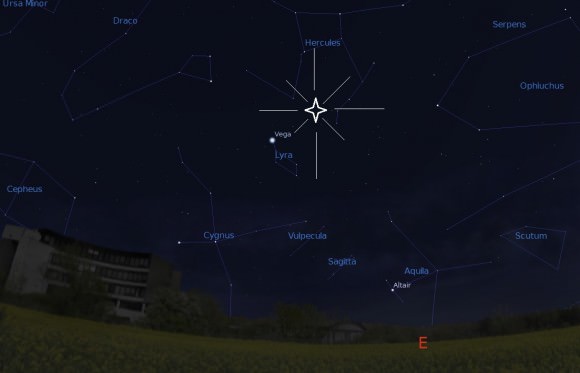

| Barnard’s Star | +9.5 | Ophiuchus | 17h 58’ | +04 42’ |

| Kapteyn’s Star | +8.9 | Pictor | 05h 12’ | -45 01’ |

| Lalande 21185 | +7.5 | Ursa Major | 11h 03’ | +35 58’ |

| Lacaille 9352 | +7.3 | Piscis Austrinus | 23h 06’ | -35 51’ |

| Struve 2398 | +9.0 | Draco | 18h 43’ | +59 37’ |

| Luyten’s Star | +9.9 | Canis Minor | 07h 27’ | +05 14’ |

| Gliese 687 | +9.2 | Draco | 17h 36’ | +68 20’ |

| Gliese 674 | +9.9 | Ara | 17h 29’ | -46 54’ |

| Gliese 412 | +8.7 | Ursa Major | 11h 05’ | +43 32’ |

| AD Leonis | +9.3 | Leo | 10h 20’ | +19 52’ |

| Gliese 832 | +8.7 | Grus | 21h 34’ | -49 01’ |

Notes on each:

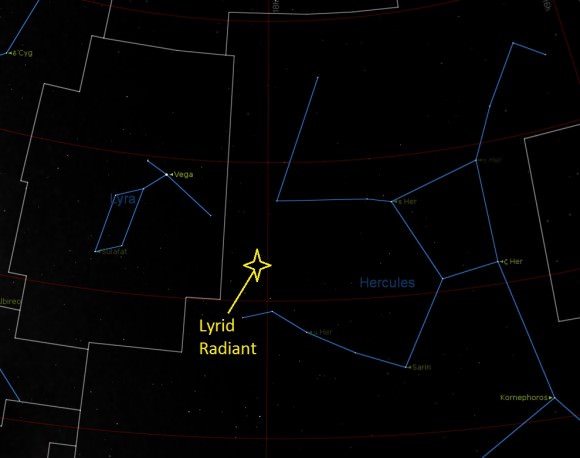

Groombridge 34: Located less than a degree from the +6th magnitude star 26 Andromedae in the general region of the famous galaxy M31, Groombridge 34 was discovered back in 1860 and has a large proper motion of 2.9″ arc seconds per year.

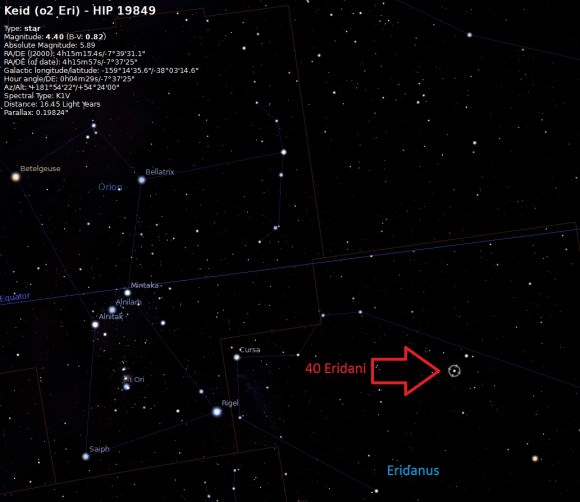

40 Eridani C: Our sole exception to the “10th magnitude or brighter” rule for this list, this multiple system is unique for containing a white dwarf, red dwarf and a main sequence K-type star all within range of a backyard telescope. In sci-fi mythos, 40 Eridani is also the host star for the planet Richese in Dune and the controversial location for Vulcan of Star Trek fame.

AX Microscopii: Also known as Lacaille 8760, AX Microscopii is 12.9 light years distant and is the brightest red dwarf as seen from the Earth at just below naked eye visibility at magnitude +6.7.

Barnard’s Star: the second closest star system to our solar system next to Alpha Centuari and the closest solitary red dwarf star at six light years distant, Barnard’s Star also exhibits the highest proper motion of any star at 10.3” arc seconds per year. The center of many controversial exoplanet claims in the 20th century, it’s kind of a cosmic irony that in this era of 1790 exoplanets and counting, planets have yet to be discovered around Barnard’s Star!

Kapteyn’s Star: Discovered by Jacobus Kapteyn in 1898, this red dwarf orbits the galaxy in a retrograde motion and is the closest halo star to us at 12.76 light years distant.

Lalande 21185: currently 8.3 light years away, Lalande 21185 will pass 4.65 light years from Earth and be visible to the naked eye in just under 20,000 years.

Lacaille 9352: 10.7 light years distant, this was the first red dwarf star to have its angular diameter measured by the VLT interferometer in 2001.

Struve 2398: A binary flare star system consisting of two +9th magnitude red dwarfs orbiting each other 56 astronomical units apart and 11.5 light years distant.

Luyten’s Star: 12.36 light years distant, this star is only 1.2 light years from the bright star Procyon, which would appear brighter than Venus for any planet orbiting Luyten’s Star.

Gliese 687: 15 light years distant, Gliese 687 is known to have a Neptune-mass planet in a 38 day orbit.

Gliese 674: Located 15 light years distant, ESO’s HARPS spectrograph detected a companion 12 times the mass of Jupiter that is either a high mass exoplanet or a low mass brown dwarf.

Gliese 412: 16 light years distant, this system also contains a +15th magnitude secondary companion 190 Astronomical Units from its primary.

AD Leonis: A variable flare star in the constellation Leo about 16 light years distant.

Gliese 832: Located 16 light years distant, this star is known to have a 0.6x Jupiter mass exoplanet in a 3,416 day orbit.

Consider this list a teaser, a telescopic appetizer for a curious class of often overlooked objects. Don’t see you fave on the list? Want to see more on individual objects, or similar lists of quasars, white dwarfs, etc in the range of backyard telescopes in the future? Let us know. And while it’s true that such stars may not have a splashy appearance in the eyepiece, part of the fun comes from knowing what you’re seeing. Some of these stars have a relatively high proper motion, and it would be an interesting challenge for a backyard astrophotographer to build an animation of this over a period of years. Hey, I’m just throwing that out project out there, we’ve got lots more in the files…