[/caption]

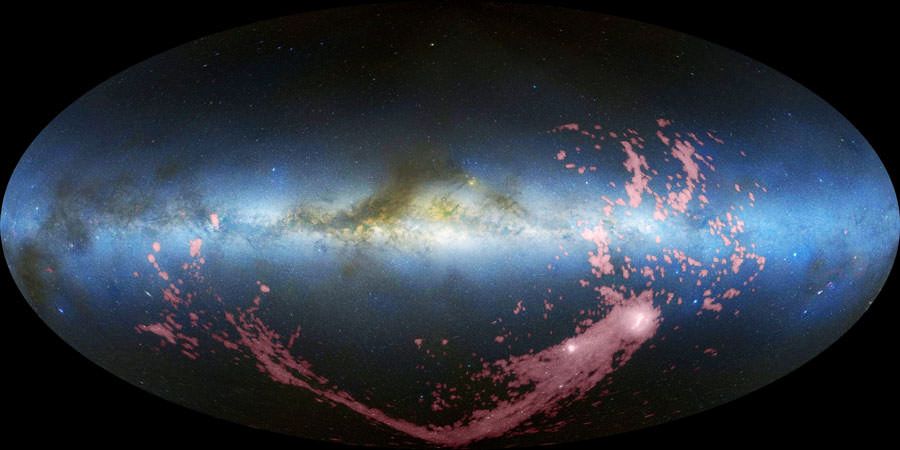

Most people agree that the Magellanic Clouds are in orbit around the Milky Way. What’s not clear is whether it is a bound orbit or just a temporary ‘ships passing in the night’ arrangement. Something which could clarify the relationship is the Magellanic Stream, a 600,000 light year long string of gas dragged through and beyond the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds.

For the complete picture, note that there is also a shorter trail of gas drawn out ahead of the Clouds, known as the Leading Arm – and the gas flow between the Clouds is known as the Magellanic Bridge. The Bridge is an indication that the Clouds are gravitationally bound in a binary pair – at least for now. The Large Magellanic Cloud may dragging the Small Magellanic Cloud behind it, since the Magellanic Stream ‘skid mark’ is most chemically similar to the contents of the Small Magellanic Cloud.

What remains unresolved is whether the Clouds are in a bound orbit around the Milky Way – or are they just passing by? The level of uncertainty about the dynamics of objects that are relatively close to us, and are easily visible to the naked eye, may seem surprising.

Firstly, it is tricky to gain an accurate estimation of each Cloud’s velocity relative to the Milky Way – partly because we, the observers, have our own independent movement and we need to find a reference frame that we can reliably measure the Clouds’ velocity against.

Estimates derived from Hubble Space Telescope observations by Kallivayalil and colleagues in 2006, measured the Clouds’ velocities against a background of distant quasars, which are visible through the Clouds. These data were then used by Besla and colleagues to propose that the Clouds’ velocities were too fast to be in bound orbits around the Milky Way and so must be just passing by.

But there is another area of uncertainty, where – even with the Clouds’ velocity determined – you still need to decide what escape velocity they need to avoid being caught in a bound orbit of the Milky Way. While we can estimate the Milky Way’s mass, there is the issue of dark matter – which we can’t see and hence can’t locate accurately – so there is some uncertainty about how the combined mass of the Milky Way’s visible and dark matter is distributed.

If, like the visible matter, the dark matter is centralized around the galactic hub, the Clouds won’t need so much velocity to escape. But if the dark matter is more evenly distributed with the galactic disk of visible matter being surrounded by a spherical halo of dark matter, then it’s less clear as to whether the Cloud’s could escape (a scenario that was acknowledged by Besla et al).

A spherical halo of dark matter is the generally preferred model for the Milky Way’s total mass distribution – since, without it, the outer edges of the Milky Way’s visible disk are rotating so fast that they should fly off into space.

Diaz and Bekki have run with this idea by computer-modeling a Milky Way with a circular velocity of 250 kilometres a second (a recent new estimate), which hence requires a more substantial dark matter halo than was assumed by Besla et al. Otherwise, they still use the same Cloud velocities determined from the 2006 Hubble Space Telescope observations.

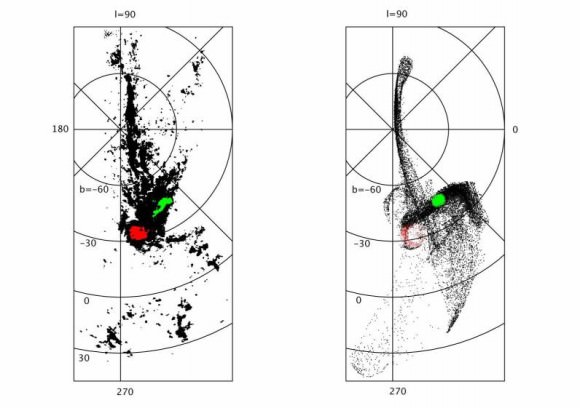

Their model, when wound back in time, suggests the Clouds have been locked in bound orbits around the Milky Way for more than 5 billion years – with the Magellanic Stream and Leading Arm arising more recently, following a close encounter between the two Clouds (an idea also proposed in Besla et al’s unbound orbit model).

Diaz and Bekki suggest that the Clouds began separate orbits, but passed close to each other around 1.25 billion years ago and then became the binary pair we observe today. The Leading Arm is freed gas being drawn into the Milky Way’s halo – an indication that both Clouds may eventually be assimilated.

Further reading: Diaz and Bekki. Constraining the orbital history of the Magellanic Clouds: A new bound scenario suggested by the tidal origin of the Magellanic Stream.

Its an interesting Conjecture. It seems hard to imagine the stream and the clouds as not in some way being related to the Milky way.

I sometimes thought of the stream as a detached Spiral arm of the milky way. 🙂

On another note, its nice to know our neighbors, even if they do throw stars at us.

HE 0437-5439 Is a hypervelocity star (2.6 million km/hour) thats hypothesized to have come from the Large Magellanic Cloud. Visitors Perhaps?

Damian – thanks for that. HE 0437-5439 is an interesting beast, although Wikipedia suggests the LMC origin remains contentious? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HE_0437-5439

Ahh, new data. In any case its traveling away from us. However there is an enigma, it seems to be made of the same stuff as the LMC (2008 study) however nobody has yet been able to verify if the LMC has a central Singularity. Which is the only thing that could have (theoretically) given it such a high velocity.

However the new 2010 study seems to have (definitively) pegged its distance, velocity and thus its origin. (As long as its a Blue Straggler, which is a kind of star that is not well understood. )

My question is, how can one group of scientists definitively pronounce the velocity of a single star but another group have trouble with the velocity of the whole Magellanic stream?

I think there is a similar level of accuracy in both velocity measures (both use HST observations). However, the star is going so fast that a bit of +/- variation makes little difference to a determination of its trajectory and destiny. The Clouds’ velocities are right at a borderline – where a bit faster would mean they are definitely unbound – a bit slower would mean they are definitely bound. So a bit of +/- variation makes all the difference to a determination of their trajectory and destiny.

Also, and maybe LBC will mass in 🙂 on this, DM halos vs discs are easier to understand from the perspective that the matter doesn’t structure as easily and is cold.

Ah yes, sort of obvious now, isn’t it?

Modulo the question on how dwarfs (?) such as the clouds arise and interact earlier, this must be one of the more important predictions of the model. Perhaps those sorts of pairs are really unlikely without being bound to larger systems.

The last time the MCs were discussed on UT I think it was in the context of such pairs being relatively rare, only a few (one other?) of such size observed around other large galaxies. If pairs are results of more energetic dynamics close to large systems, it could be that they will happen but dwarfs are eventually ripped to pieces and assimilated. “Resistance is futile!”

Except that larger dwarfs should orbit for longer times until the process is complete, I assume resulting in a selection effect for the making of large pairs. Another selection effect, but for the observation of few pairs, would be that they seem to facilitate their own destruction: “with the Magellanic Stream and Leading Arm arising more recently, following a close encounter between the two Clouds”.

“While we can estimate the Milky Way’s mass, there is the issue of dark matter – which we can’t see…” Kepler to the rescue?