The two largest reservoirs in the United States are now at their lowest levels since they were first created. After several decades of drought – with the past two years classified as intense drought in the US Southwest — both Lake Powell and Lake Mead are shrinking. Recent satellite images show just how dramatic the changes have been, due to the ongoing the climate crisis..

We wrote about Lake Mead last fall, and now new images of Lake Powell show the detrimental effects the drought has had. Lake Powell now bears little resemblance to a lake.

Both Lake Mead and Lake Powell are on the Colorado River. Lake Mead was created in 1935 and Lake Powell in 1963. Both provide water to approximately 40 million people. Lake Powell also irrigates over 2.2 million hectares of land and has the capacity to generate more than 4,200 megawatts of hydropower electricity.

The Glen Canyon Dam holds back the waters of the Colorado River, forming the large Lake Powell, which straddles the border of southeastern Utah and northeastern Arizona. Remarkably, after the dam was built, it took 17 years for the lake to fill the canyon to the high-water mark at 1,130 meters (3,700 feet) above sea level), becoming the US’s second largest human-made lake, after Lake Mead.

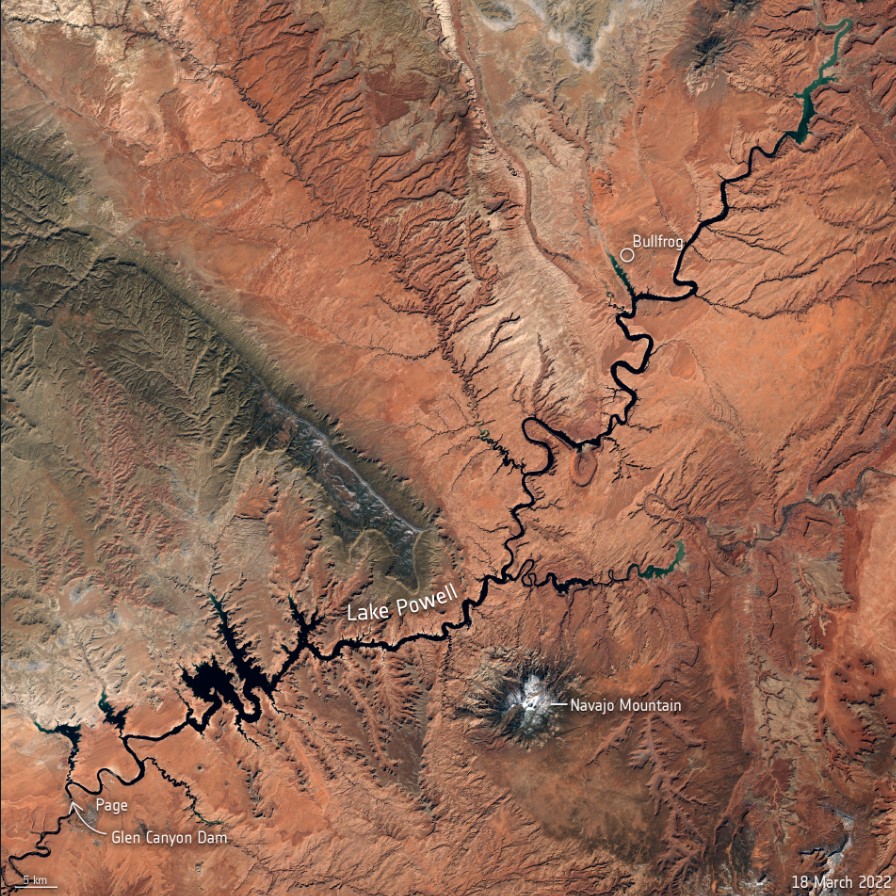

But in mid-March 2022, Lake Powell’s elevation dropped to just 1,074 meters (3,520 ft) above sea level – the lowest the lake has been since it was filled in 1980. The lake now holds less than 30% of its capacity. This drastic drop in water levels is shown here below in natural-color images captured by ESA’s Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission.

The area pictured above shows the surface area changes of the reservoir near Bullfrog Marina, approximately 90 km north from Glen Canyon Dam, between March 2018 and March 2022. Dry conditions and falling water levels are unmistakable in the image captured on March 18, 2022, compared to the 2018 shoreline outlined in the image in yellow.

The drop in water levels comes as hotter temperatures and falling water levels left a smaller amount of water flowing through the Colorado River. The peak inflow to Lake Powell occurs in mid-to-late spring, as the winter snow in the Rocky Mountains melts.

To compensate for the low water levels, federal managers have started releasing water from upstream reservoirs to help keep Lake Powell from dropping below a threshold that threatens hydropower equipment at the dam.

This line graph shows the drastic drop in average water levels in March since 2000, when Lake Powell was at around 1,120 meters (3,670 ft) elevation. The current elevation is just a few meters from what is considered the ‘minimum power pool’ – the level at which Glen Canyon Dam is able to generate hydroelectric power. If Lake Powell drops even more, it could soon hit a ‘deadpool’ where water will likely fail to flow through the dam and onto the nearby Lake Mead.

Forecasters predict these conditions are likely to continue across more than half of the continental United States through at least June, straining water supplies and increasing the risk of wildfires. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) the latest outlook for the US, nearly 60% of the continental US is experiencing drought.

Lead image caption: This Copernicus Sentinel-2 image allows us a wider view of Lake Powell and its dwindling water levels amidst the climate crisis. Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2022), processed by ESA.

Sources: ESA, NASA Earth Observatory