There are instances other than pandemics when it is necessary to work remotely. Spacecraft operators are forced to do most of their work remotely while their charges travel throughout the solar system. Sometimes those travels take place a little closer to home. Engineers at DLR, Germany’s space agency, recently got to take the concept of remote working to a whole new level when they operated a rover in a whole different country almost 700 kilometers away while working remotely from their primary office.

The rover, known as Interact, was located in the European Space Research Technology Center, the “technical heart” of ESA operations in Noordwijk, Netherlands. Interact’s operators were located at DLR’s Instute for Robotics and Mechatronics, near Munich. As with all good space missions, the operators did not operate alone. They had the support of a “mission control” center located at ESA’s European Space Operations Center in Darmstadt.

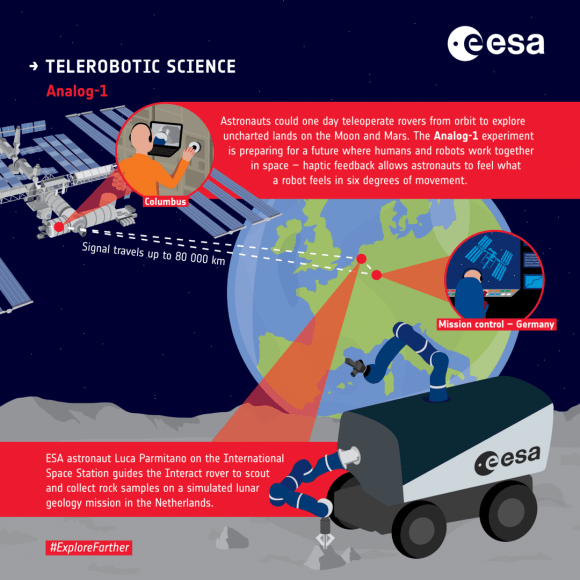

Interact itself is a tool to test how remote operation might be possible for future ESA rovers located on the moon. Any future lunar rover could potentially be controlled by operators located in the Lunar Gateway or a similar space station.

Any remote operation out of Earth’s orbit probably wouldn’t need to deal with the impact of the current pandemic. Unfortunately, Interact is stuck here on the ground like the rest of us. That means they are also susceptible to COVID-related delays. Originally the ESA team in charge of Interact was planning on an excursion to Mount Etna, an active volcano on Sicily with the most moon-like geography in Europe. Travel restrictions nixed that idea, so the team did what space explorers do best – they adapted.

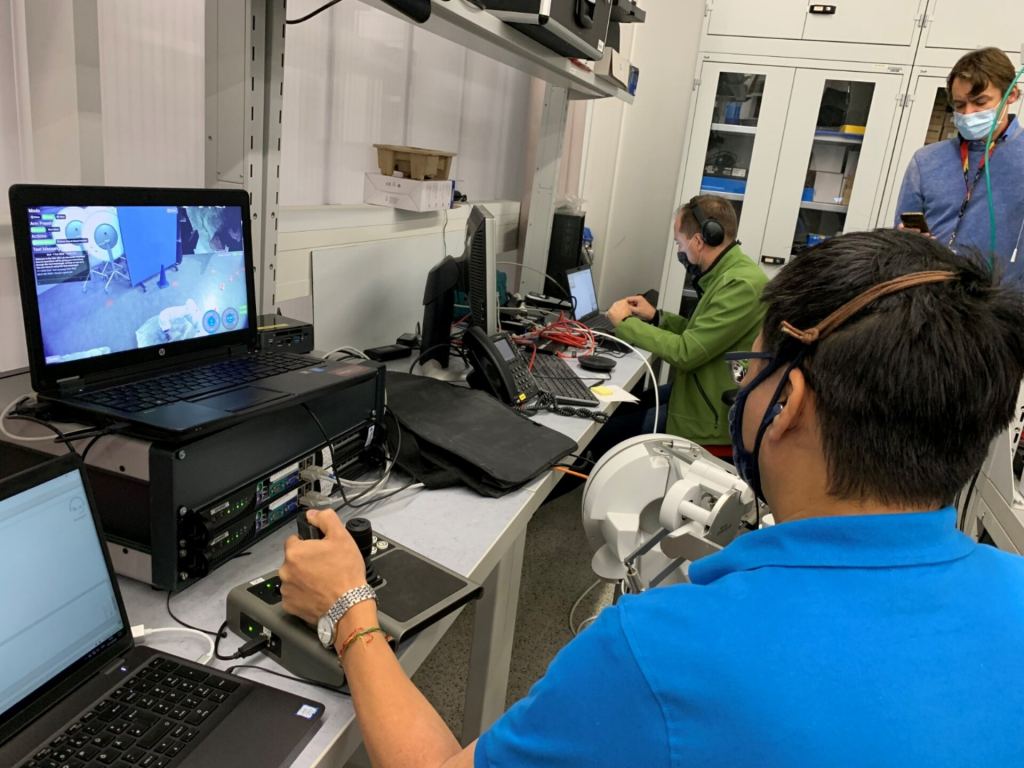

Credit: ESA – SJM Photography

That adaptation took the form of a redefined remote operational test. Instead of operating the robot remotely on the slopes of Mount Etna, ESA and their collaborators at DLR could set up the robot anywhere they wanted it and then operate it remotely. Just for an added challenge, they also added another robot to the mix.

A smaller robot, based in Germany, was networked in with the Interact rover in an effort to get the two bots to coordinate while operating in a remote environment. Even though they were not physically near each other, their operating logic was tricked into thinking they were. The team hoped to allow the two bots to move in tandem similarly to how they would be expected to when they actually are co-located.

All this successful remote operation and testing is part of an ongoing effort to stretch the capability of humans interacting with robots. The program, called Meteron for the Multi-purpose End-to-End Robotic Operation Network is hosted by ESA’s Human Robotic Interaction Laboratory (HRI).

HRI’s team is still trying to tackle some of the more difficult aspects of remote robot control, including lag and tactile feedback. Despite the operation being in near real time, there will always be a communication lag when an operator is controlling an object that is hundreds or thousands of kilometers away. How operators deal with that control lag is a subject of ongoing study by HRI’s team, and tests like the one with Interact are a key component to solving that puzzle.

Credit: DLR

Another difficulty in remote operation is how to convey the robot’s sense of touch. Haptic feedback, such as one would expect to feel when a robotic arm touches the ground, has taken off in a different field though – video games. Advanced flight sticks and video game controls are capable of conveying a sense of touch to an operator, and the HRI team has implemented those feedback responses into Interact’s control system.

These improvements to Interact follow repeated successful milestones for the proof of concept robot. The most recent of these took place last year when Interact was remotely controlled by an astronaut on the ISS.

Credit: ESA

Hopefully ESA won’t have to resort to such long distance control when it finally does take Interact to Mount Etna for testing next summer. If all things go as planned, eventually astronauts won’t be controlling rovers only on the surface of the Earth, but some on the Moon as well.

Learn More:

ESA – ESA’s force-feedback rover controlled from a nation away

UT – ESA is Going to Test Two Rovers Working Together to Explore the Moon

UT – This Laser Powered Rover Could Stay in the Shadows on the Moon and Continue to Explore

Feature Image Credit: Interact rover under remote operation.

Credit: ESA – SJM Photography