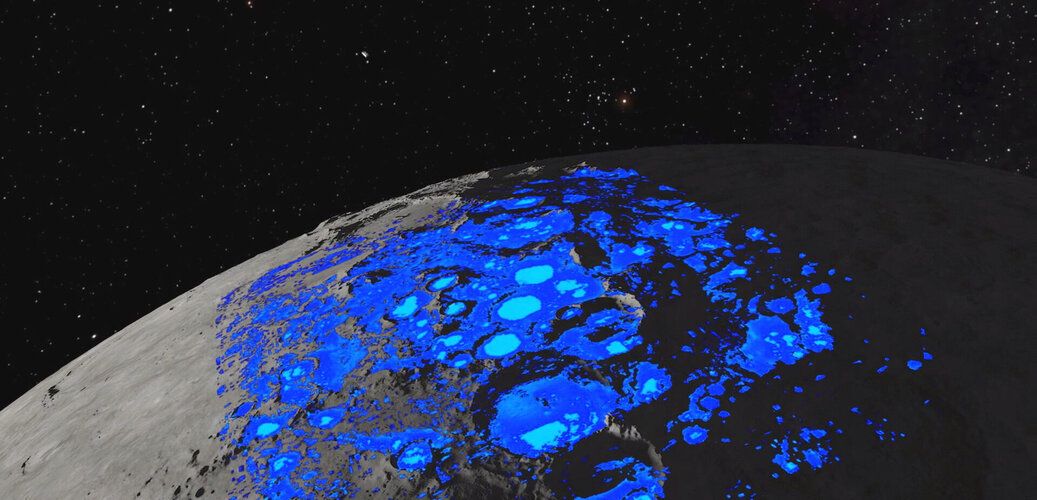

In 2009, NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), the first mission to be sent by the US to the Moon in over a decade. Once there, the LRO conducted observations that led to some profound discoveries. For instance, in a series of permanently-shaded craters around the Moon’s South Pole-Aitken Basin, the probe confirmed the existence of abundant water ice.

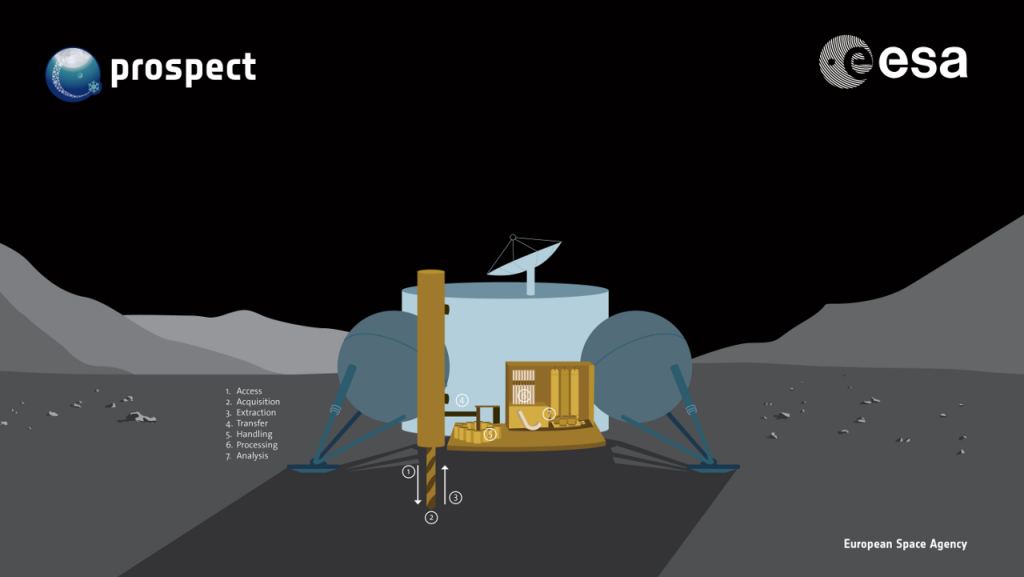

Based on the temperature data obtained by the LRO of the Moon’s southern polar region, the ESA recently released a map of lunar water ice (see animation below) that will be accessible to future missions. This includes the ESA’s Package for Resource Observation and in-Situ Prospecting for Exploration, Commercial exploitation and Transportation (PROSPECT), which will be flown to the Moon by Russia’s Luna-27 lander in 2025.

Once there, PROSPECT will sample these caches of water ice in order to assess the potential of future missions to harvest them for the sake of constructing and maintaining a lunar outpost – i.e. In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU). Central to this process is the ProSEED, a drill that will extract samples from beneath the surface of the Moon’s South Pole region.

In addition to water, these samples are expected to contain other volatiles that can become trapped at the extremely low temperatures that are expected in this region – typically -150 °C (-238 °F) and lower than -200 °C (-328 °F) in some areas. These samples will then be heated and analyzed by PROSPECT chemical laboratory (ProSPA) to extract these volatiles and subject them to thermochemical processes.

This will involve heating them to temperatures of up to 1000 °C (1832 °F) to test if other chemical compounds (like oxygen gas) can be extracted. The purpose of this is to determine if local resources can be harvested and converted to meet the needs of astronauts and lunar colonists someday – such as producing construction materials, drinking water, and even air.

For her role in developing this improved method of extracting lunar water, Hannah Sargeant of the UK’s Open University was named one of Forbes Magazine’s 30 Under 30 Europe 2020 Innovation list. As Hannah described this honor:

“It’s great to see that research into space resources is being recognized and valued in such a public forum… I’m honored to be a part of this year’s Forbes 30 Under 30 European cohort, but I would like to emphasize that there are many incredible researchers that I work with that are so deserving of a place on this list. The future of space science and technology is definitely in great hands!”

The ProSPA lab will also analyze these samples to get precise isotopic measurements of key elements on the Moon – such as carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and hydrogen. This will provide insight into the origins, evolution, and placement of volatile chemicals within the Earth-Moon system, but also help astronomers to get a better idea of how volatiles have been distributed throughout the inner Solar System.

Much like the distribution of water, knowing how, when, and where these elements were distributed is key to understanding how our Solar System evolved over time. Since these chemicals are also key to the existence of life as we know it, a volatile record could also provide insight into when life emerged and where else it could be found.

Both PROSPECT and the Russian Luna-Glob program are part of a larger global effort to explore the Moon and prospect for resources. The long-term aim of these missions, along with Project Artemis and the construction of the Lunar Gateway, is to create a sustainable program for lunar exploration and a permanent human presence on the Moon.

Further Reading: ESA