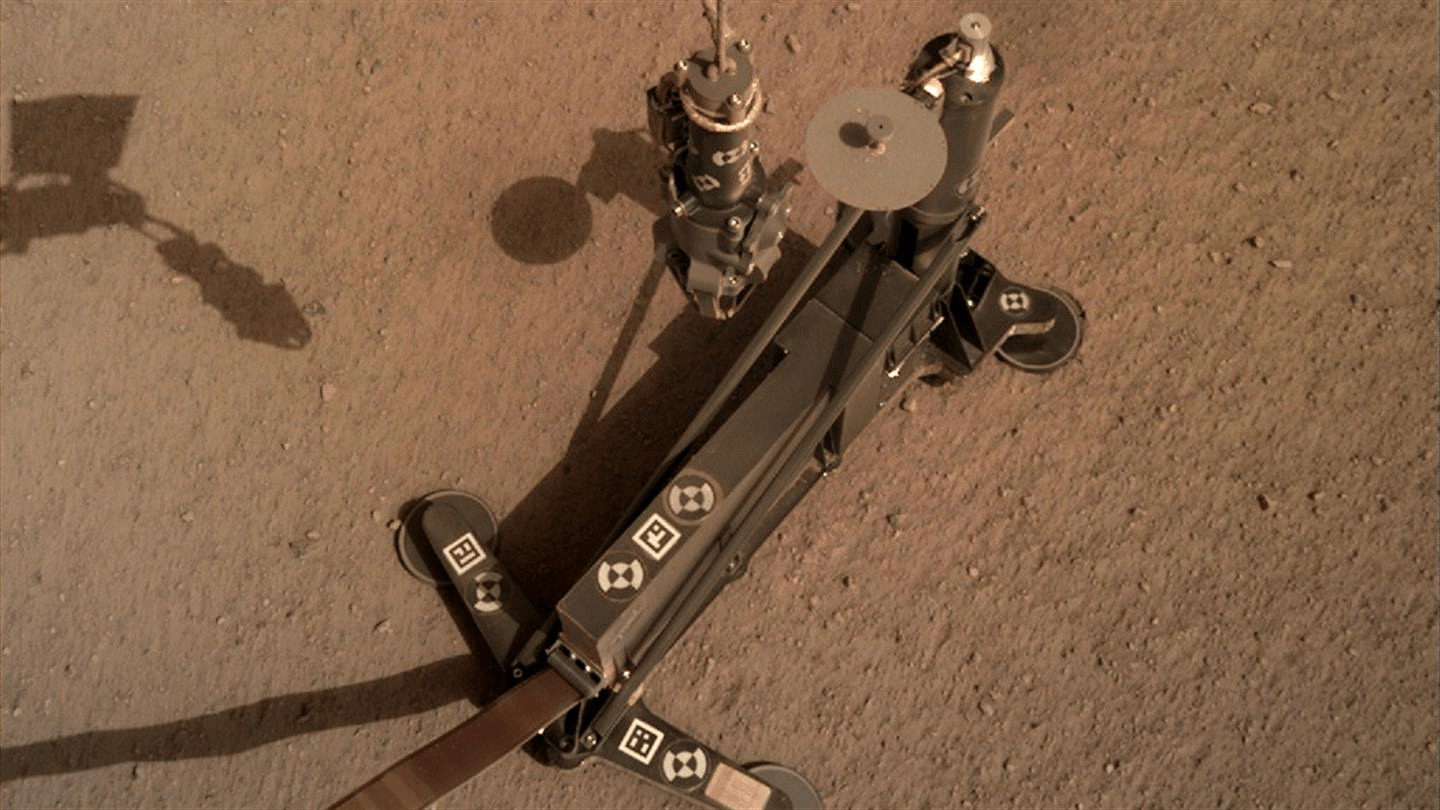

NASA’s InSight lander is busy deploying its Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) into the Martian soil and has encountered some resistance. The German Aerospace Center (DLR), who designed and built the HP3 as part of the InSight mission, has announced that the instrument has hit not one, but two rocks in the sub-surface. For now the HP3 is in a resting phase, and it’s not clear what will happen next.

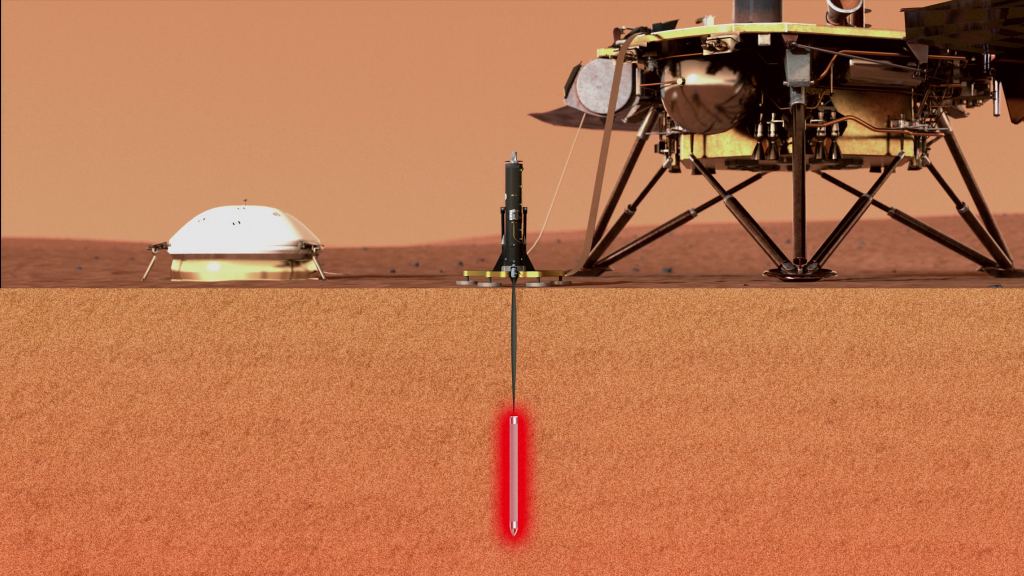

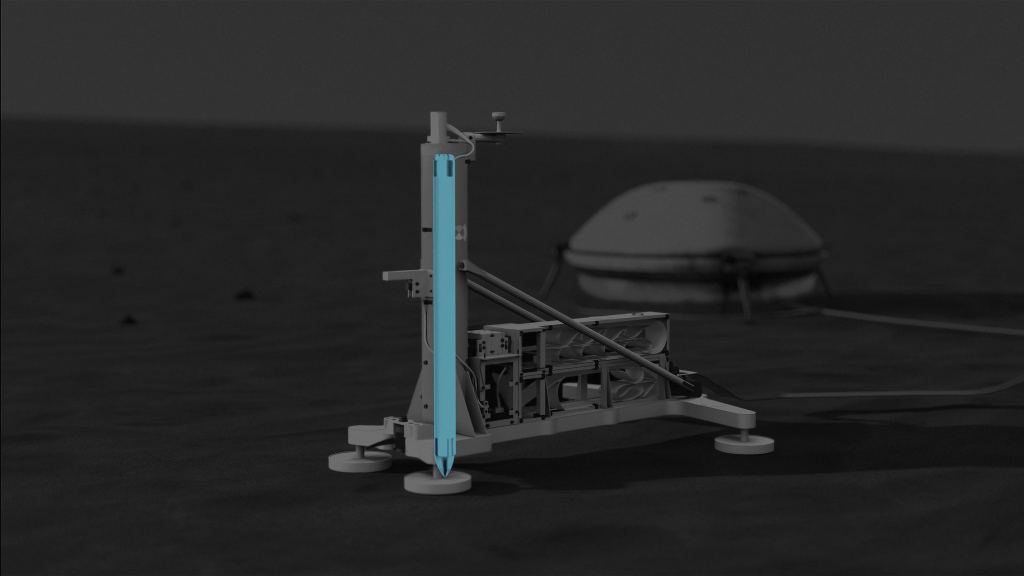

The HP3 is designed to measure the heat coming from Mars’ interior and to tell us something about the source of that heat. The basic idea is to determine how Mars formed, and if it formed the same way Earth did. It’ll also tell us something about how rocky planets in general form and evolve. But to do that, it has to get underground.

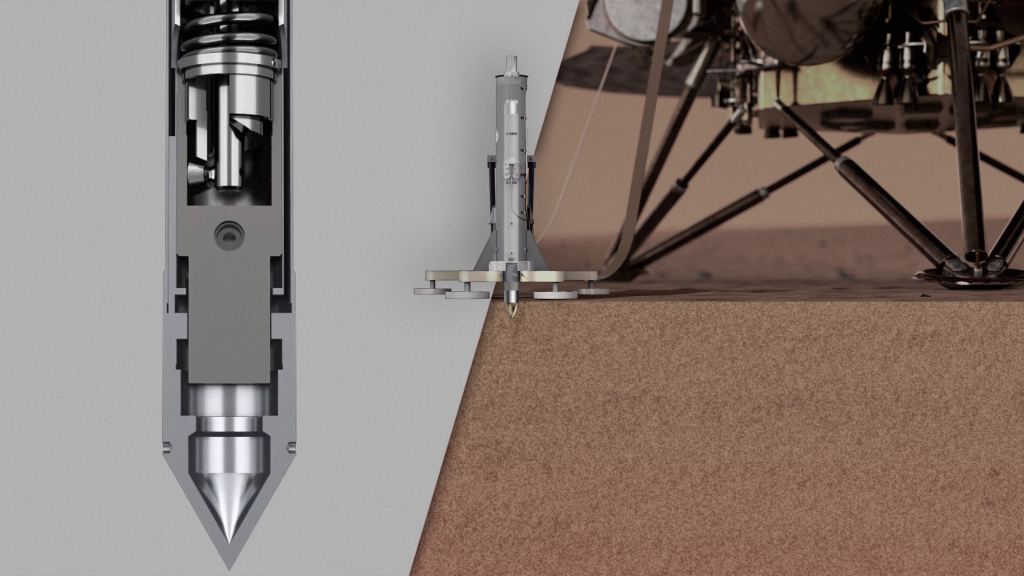

The HP3 uses a hammer system to pound itself into the ground. It works in phases, spending about four hours at a time hammering into the surface. But all that hammering creates a lot of friction and heat, so the HP3 rests for a couple days while things cool down. Then it measures the heat before continuing the cycle.

“On its way into the depths, the mole seems to have hit a stone, tilted about 15 degrees and pushed it aside or passed it.”

Tilman Spohn, Principal Investigator of the HP3 experiment.

The DLR has announced in a press release that HP3 has encountered some resistance.

On February 12th the HP3 was deployed onto the Martian surface, and on the 28th the HP3 began hammering its way into the subsurface. The part of the probe that does the hammering is called the ‘mole.’ During its first four-hour hammering sequence the mole penetrated to about 50 cm. During that time, it encountered a rock, and either passed it by or managed to push it out of the way.

DLR (CC-BY 3.0)

“On its way into the depths, the mole seems to have hit a stone, tilted about 15 degrees and pushed it aside or passed it,” reports Tilman Spohn, Principal Investigator of the HP3 experiment.

HP3 encountered the first rock and was able to keep going. However, it encountered a second rock that impeded the mole’s penetration. “The Mole then worked its way up against another stone at an advanced depth until the planned four-hour operating time of the first sequence expired,” said Spohn. “Tests on Earth showed that the rod-shaped penetrometer is able to push smaller stones to the side, which is very time-consuming.”

The ideal operating depth for the probe is five meters. At that depth, the probe is well-isolated from surface temperature fluctuations. However, the probe can still do its thing at a depth as shallow as three meters, the data just requires more processing and ‘cleaning.’ But with this second rock encounter, the mole is nowhere near the needed operating depth of three meters.

DLR (CC-BY 3.0)

With the mole at a 15 degree angle, and up against a second rock, the DLR planned to let it cool off for a couple days, then initiate another four-hour hammering sequence. At least that was their plan on March 1st. But now it looks like they’ve changed their mind.

Tilman Spohn, HP3 Principal Investigator, DLR.

“The team has therefore decided to pause the hammering for about two weeks to allow the situation to be analysed more closely and jointly come up with strategies for overcoming the obstacle.”

The DLR team has now decided to take a couple weeks to analyze the situation thoroughly and come up with a course of action.

“The team has therefore decided to pause the hammering for about two weeks to allow the situation to be analysed more closely and jointly come up with strategies for overcoming the obstacle,” writes Tilman Spohn of the DLR Institute of Planetary Research, Principal Investigator of the HP3 experiment, on his InSight mission blog.

InSight isn’t a rover; it’s a lander. It can’t move around the Martian surface to select a spot for the HP3. Its landing site was chosen because it appears to be rock free on the surface, and mission planners hoped that would indicate a relatively rock-free sub-surface. The InSight team also spent weeks after landing to select the best spot to deploy the HP3, examining its immediate surroundings for the most rock-free spot. But there was never any guarantee.

It’s difficult to know if this recent development is a serious obstacle to the HP3 mission, or just the kind of hiccup that planners expected. As mentioned previously, the mole is capable of pushing small rocks out of its way, as testing on Earth showed. But that takes time, and if the mole is able to work its way past this obstacle, it could easily meet another rock. Perhaps an immovable one.

So far, even with the rocky obstacles, the mole and the HP3 are operating as intended. During the four-hour hammering phase, the mole heated up by 28 degrees Celsius, and then measured how quickly the surrounding soil absorbed that heat. That’s called thermal conductivity, and measuring that conductivity is how the HP3 can measure the heat flow from deep inside the planet. But depth matters.

Even though it’s operating as intended, it’s not deep enough to tell scientists much yet. It’s crucial that the mole penetrates to at least three meters deep. And the deeper the better, with the maximum depth of five meters being the best case scenario, and providing the best scientific results.

It would be a huge blow to the InSight Lander mission if the HP3 could not penetrate to the correct depth. It wouldn’t be catastrophic however, as long as the lander’s other instruments can still do their job.