Since the turn of the century, China has worked hard to become one of the fastest-rising powers in space. In 2003, the Chinese National Space Administration (CNSA) began sending their first taikonauts to space with the Shenzou program. This was followed by the deployment of the Tiangong-1 space station in 2011 and the launch of Tiangong-2 in 2016. And in the coming years, China also has its sights set on the Moon.

But before China can conduct crewed lunar missions, they must first explore the surface to locate safe landing spots and resources. This is the purpose behind the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program (aka. the Chang’e program). Named after the Chinese goddess of the moon, this program made history yesterday (Thursday, Jan. 3rd) when the fourth vehicle to bear the name (Chang’e-4) landed on the far side of the Moon.

The Chang’e-4 mission, which was first announced in 2015, consists of a lunar lander and a rover (Yutu-2, or “Jade Rabbit”), similar to the Chang’e-3 mission. On May 20th, 2018 – shortly before the mission launched – China sent a satellite (Queqiao) to the Earth-Moon L2 Lagrange Point to relay communications between the lander and rover (since direct communication with the far side of the Moon is impossible).

According to state Chinese media, the combination lander-rover touched down on the lunar surface at 10:26 am Beijing time on January 3rd, 2019 (22:26 EDT; 19:26 PST on Jan. 2nd). This was an historic accomplishment, as no space agency in the history of space flight has managed to land a mission on the “dark side” of the Moon.

The Chang’e-4 mission then launched on Dec. 8th, 2018, and entered a lunar orbit four days later. There it remained for 22 days as mission controllers tested its systems and waited for the Sun to rise above the pre-selected landing site – the Von Karman Crater in the South Pole-Aitken Basin. On Monday, Dec. 31st at 10:26 Beijing time (21:26 EDT; 18:26 PST on Jan. 1st), the lander-probe combination began to slowly descend.

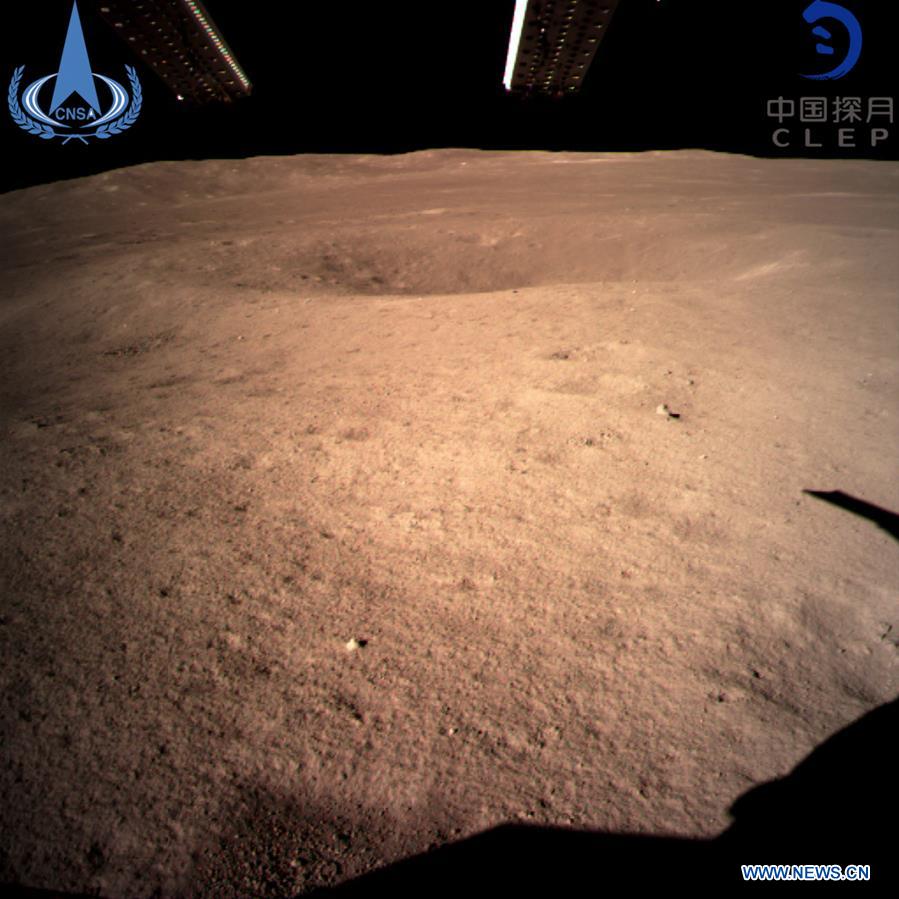

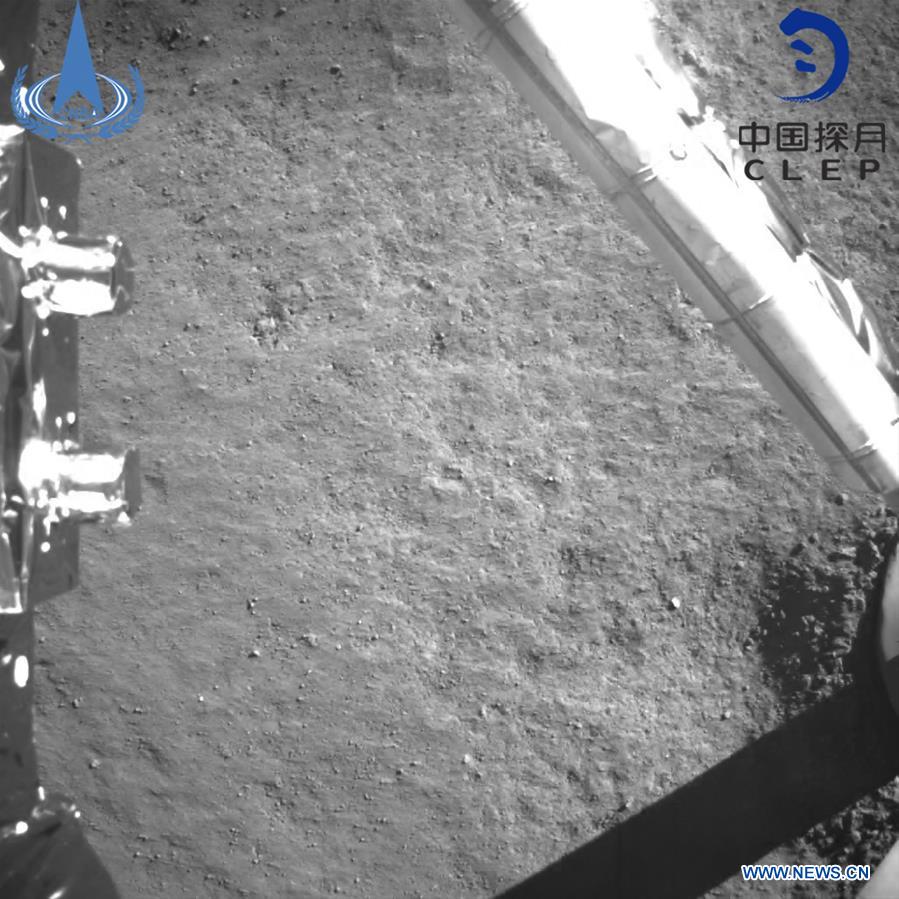

During the descent, the lander took pictures of the terrain (shown at top and above) while also hovering to make sure that there weren’t any obstacles in the landing area. Once the mission controllers determined that it was clear, the lander-rover touched down. One of the first tasks of the mission will be to deploy the Yutu-2 rover, which is similar to the rover that was part of the Chang’e-3 mission in 2013.

In what will be another first in space exploration, the Chang’e-4 rover will explore the South Pole-Aitken Basin, a vast impact region in the Moon’s southern hemisphere that is believed to have formed roughly 4 billion years old (as a result of a massive impact). Measuring roughly 2,500 km (1,600 mi) in diameter and 13 kilometers (8.1 mi) deep, it is the largest impact basin on the Moon and one of the largest in the Solar System.

This site was selected because of the vast amounts of water ice discovered there in recent years. It is widely believed that this ice was deposited by meteors and asteroids, and has remained there because of how the region is permanently shadowed. While the Basin has been studied from orbit on multiple occasions, Yulu-2 will be the first mission to study it directly.

By studying this ancient basin, the Chang’e-4 mission is expected to provide insights about the early history of the Solar System. The presence of water ice is also the reason that this site has been proposed as a possible location of a permanent lunar outpost. The European Space Agency has even proposed building International Lunar Village in this area by the 2030s.

On top of that, the fact that this mission is taking place on the far side of the Moon presents some unique opportunities for experiments in radio astronomy. For this reason, the Queqiao satellite was equipped with a radio antenna – the Netherlands-China Low-Frequency Explorer (NCLE) – and will be carrying out astrophysical studies using unexplored radio wavelengths.

Last, but not least, the lander will be testing the effects of lunar gravity on living creatures. This will be done through it’s Lunar Micro Ecosystem, a stainless steel container measuring 18 cm (in) long and 16 cm (in) in diameter. This cylinder contains seeds and insect eggs, as well as all the air and heat they will need to survive, and will test whether plants and insects could hatch and grow in lunar gravity.

The successful landing of the Chang’e-4 mission was not only an historic accomplishment. Given the objectives of the mission, it also signaled the beginning of a new era of lunar exploration. In the coming years, the information this and other missions provide will help set the stage for crewed missions back to the Moon. They will also help with the long-term goal of establishing a permanent human presence there.

As has been said many times before, we’re going back to the Moon, and we plan to stay there! Best of all, we’re getting closer to that goal. And while we’re waiting, be sure to check out this video of the successful landing, as witnessed by the mission personnel at the Beijing Aerospace Control Center, courtesy of New China TV:

Further Reading: Xinhuanet, Planetary Society