In their efforts to find evidence of life beyond our Solar System, scientists are forced to take what is known as the “low-hanging fruit” approach. Basically, this comes down to determining if planets could be “potentially habitable” based on whether or not they would be warm enough to have liquid water on their surfaces and dense atmospheres with enough oxygen.

This is a consequence of the fact that existing methods for examining distant planets are largely indirect and that Earth is only one planet we know of that is capable of supporting life. But what if planets that have plenty of oxygen are not guaranteed to produce life? According to a new study by a team from Johns Hopkins University, this may very well be the case.

The findings were published in a study titled “Gas Phase Chemistry of Cool Exoplanet Atmospheres: Insight from Laboratory Simulations“, which was recently published in the scientific journal ACS Earth and Space Chemistry. For the sake of their study, the team simulated the atmospheres of extra-solar planets in a laboratory environment to demonstrate that oxygen is not necessarily a sign of life.

On Earth, oxygen gas constitutes about 21% of the atmosphere and emerged as a result of photosynthesis, which culminated in the Great Oxygenation Event (ca. 2.45 billion years ago). This event drastically changed the composition of Earth’s atmosphere, going from one composed of nitrogen, carbon dioxide and inert gases to the nitrogen-oxygen mix we know today.

Because of its importance to the rise of complex life forms on Earth, oxygen gas is considered one of the most important biosignatures when looking for possible indications of life beyond Earth. After all, oxygen gas is the result of photosynthetic organisms (such as bacteria and plants) and is consumed by complex animals like insects and mammals.

But when it comes right down to it, there is much that scientists don’t know about how different energy sources initiate chemical reactions and how those reactions can create biosignatures like oxygen. While researchers have run photochemical models on computers to predict what exoplanet atmospheres might be able to create, real simulations in a laboratory environment have been lacking.

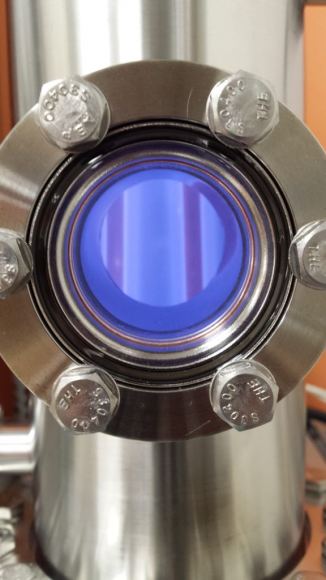

The research team conducted their simulations using the specially designed Planetary HAZE (PHAZER) chamber in the lab of Sarah Hörst, an assistant professor of Earth and planetary sciences at JHU and one of the principle authors on the paper. The researchers began by creating nine different gas mixtures to simulate exoplanet atmospheres.

These mixtures were consistent with predictions made about the two most common types of exoplanet in our galaxy – Super-Earths and mini-Neptunes. Consistent with these predictions, each mixture was composed of carbon dioxide, water, ammonia and methane, and was then heated to temperatures ranging from 27 to 370 °C (80 to 700 °F).

The team then injected each mixture into the PHAZER chamber and exposed them to one of two forms of energy known to trigger chemical reactions in atmospheres – plasma from an alternating current and ultraviolet light. Whereas the former simulated electrical activities like lightning or energetic particles, the UV light simulated light from the Sun – the main driver of chemical reactions in the Solar System.

After running the experiment continuously for three days, which corresponds to how long atmospheric gases would be exposed to an energy source in space, the researchers measured and identified the resulting molecules with a mass spectrometer. What they found was that in multiple scenarios, oxygen and organic molecules were produced. These included formaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide, which can lead to the production of amino acids and sugars.

In short, the team was able to demonstrate that oxygen gas and the raw materials from which life could emerge could both be created through simple chemical reactions. As Chao He, the lead author on the study, explained:

“People used to suggest that oxygen and organics being present together indicates life, but we produced them abiotically in multiple simulations. This suggests that even the co-presence of commonly accepted biosignatures could be a false positive for life.”

This study could have significant implications when it comes for the search for life beyond our Solar System. In the future, next-generation telescopes will give us the ability to image exoplanets directly and obtain spectra from their atmospheres. When that happens, the presence of oxygen may need to be reconsidered as a potential sign for habitability. Luckily, there are still plenty of potential biosignatures to look for!

Further Reading: JHU, ACS Earth and Space Chemistry

It is possible to have Oxygen generated by some chemical reactions but Oxygen being corrosive in nature requires a equilibrium cycle where Oxygen is continuously generated to replenish the Oxygen lost due to Oxidation.

On earth it is done by photo-synthesis and that is indicator of life evolution.