In 2006, during their 26th General Assembly, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) adopted a formal definition of the term “planet”. This was done in the hopes of dispelling ambiguity over which bodies should be designated as “planets”, an issue that had plagued astronomers ever since they discovered objects beyond the orbit of Neptune that were comparable in size to Pluto.

Needless to say, the definition they adopted resulted in fair degree of controversy from the astronomical community. For this reason, a team of planetary scientists – which includes famed “Pluto defender” Alan Stern – have come together to propose a new meaning for the term “planet”. Based on their geophysical definition, the term would apply to over 100 bodies in the Solar System, including the Moon itself.

The current IAU definition (known as Resolution 5A) states that a planet is defined based on the following criteria:

“(1) A “planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

(2) A “dwarf planet” is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape , (c) has not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

(3) All other objects , except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to collectively as “Small Solar-System Bodies”

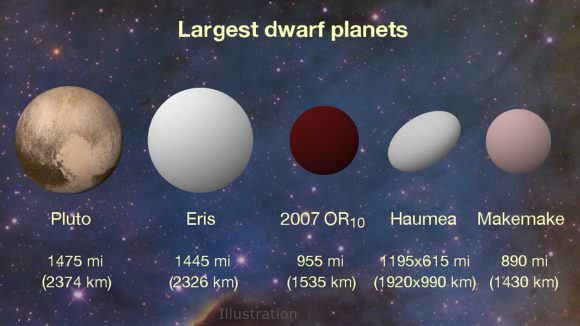

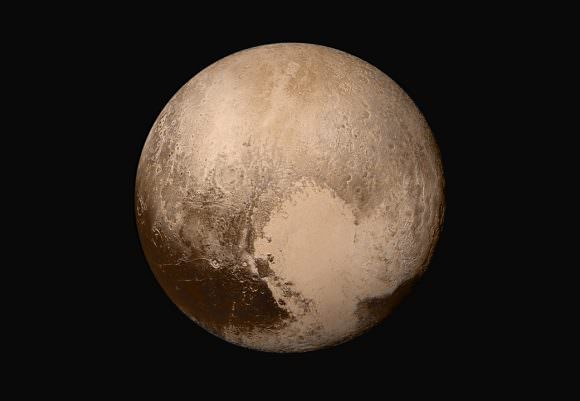

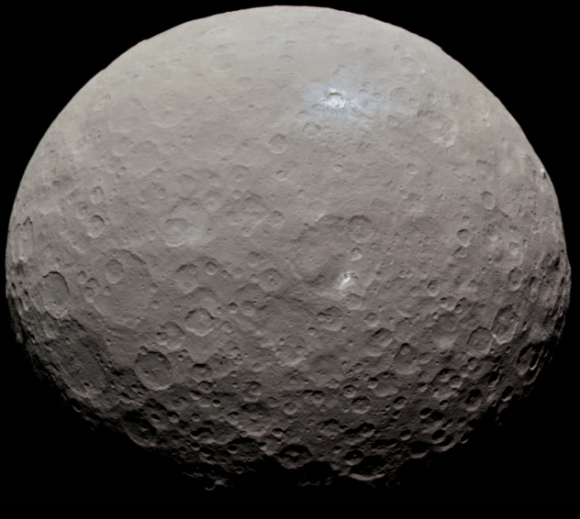

Because of these qualifiers, Pluto was no longer considered a planet, and became known alternately as a “dwarf planet”, Plutiod, Plutino, Trans-Neptunian Object (TNO), or Kuiper Belt Object (KBO). In addition, bodies like Ceres, and newly discovered TNOs like Eris, Haumea, Makemake and the like, were also designated as “dwarf planets”. Naturally, this definition did not sit right with some, not the least of which are planetary geologists.

Led by Kirby Runyon – a final year PhD student from the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Johns Hopkins University – this team includes scientists from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado; the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Tuscon, Arizona; the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona; and the Department of Physics and Astronomy at George Mason University.

Their study – titled “A Geophysical Planet Definition“, which was recently made available on the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) website – addresses what the team sees as a need for a new definition that takes into account a planet’s geophysical properties. In other words, they believe a planet should be so-designated based on its intrinsic properties, rather than its orbital or extrinsic properties.

From this more basic set of parameters, Runyon and his colleagues have suggested the following definition:

“A planet is a sub-stellar mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and that has sufficient self-gravitation to assume a spheroidal shape adequately described by a triaxial ellipsoid regardless of its orbital parameters.”

As Runyon told Universe Today in a phone interview, this definition is an attempt to establish something that is useful for all those involved in the study of planetary science, which has always included geologists:

“The IAU definition is useful to planetary astronomers concerned with the orbital properties of bodies in the Solar System, and may capture the essence of what a ‘planet’ is to them. The definition is not useful to planetary geologists. I study landscapes and how landscapes evolve. It also kind of irked me that the IAU took upon itself to define something that geologists use too.

“The way our brain has evolved, we make sense of the universe by classifying things. Nature exists in a continuum, not in discrete boxes. Nevertheless, we as humans need to classify things in order to bring order out of chaos. Having a definition of the word planet that expresses what we think a planet ought to be, is concordant with this desire to bring order out of chaos and understand the universe.”

The new definition also attempts to tackle many of the more sticky aspects of the definition adopted by the IAU. For example, it addresses the issue of whether or not a body orbits the Sun – which does apply to those found orbiting other stars (i.e. exoplanets). In addition, in accordance with this definition, rogue planets that have been ejected from their solar systems are technically not planets as well.

And then there’s the troublesome issue of “neighborhood clearance”. As has been emphasized by many who reject the IAU’s definition, planets like Earth do not satisfy this qualification since new small bodies are constantly injected into planet-crossing orbits – i..e Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). On top of that, this proposed definition seeks to resolve what is arguably one of the most regrettable aspects of the IAU’s 2006 resolution.

“The largest motivation for me personally is: every time I talk about this to the general public, the very next thing people talk about is ‘Pluto is not a planet anymore’,” said Runyon. “People’s interest in a body seems tied to whether or not it has the name ‘planet’ labelled on it. I want to set straight in the mind of the public what a planet is. The IAU definition doesn’t jive with my intuition and I find it doesn’t jive with other people‘s intuition.”

The study was prepared for the upcoming 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference. This annual conference – which will be taking place this year from March 20th-24th at the Universities Space Research Association in Houston, Texas – will involve specialists from all over the worlds coming together to share the latest research findings in planetary science.

Here, Runyon and his colleagues hope to present it as part of the Education and Public Engagement Event. It is his hope that through an oversized poster, which is a common education tool at Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, they can show how this new definition will facilitate the study of the Solar System’s many bodies in a way that is more intuitive and inclusive.

“We have chosen to post this in a section of the conference dedicated to education,” he said. “Specifically, I want to influence elementary school teachers, grades K-6, on the definitions that they can teach their students. This is not the first time someone has proposed a definition other than the one proposed by the IAU. But few people have talked about education. They talk among their peers and little progress is made. I wanted to post this in a section to reach teachers.”

Naturally, there are those who would raise concerns about how this definition could lead to too many planets. If intrinsic property of hydrostatic equilibrium is the only real qualifier, then large bodies like Ganymede, Europa, and the Moon would also be considered planets. Given that this definition would result in a Solar System with 110 “planets”, one has to wonder if perhaps it is too inclusive. However, Runyon is not concerned by these numbers.

“Fifty states is a lot to memorize, 88 constellations is a lot to memorize,” he said. “How many stars are in the sky? Why do we need a memorable number? How does that play into the definition? If you understand the periodic table to be organized based on the number of protons, you don’t need to memorize all the atomic elements. There’s no logic to the IAU definition when they throw around the argument that there are too many planets in the Solar System.”

Since its publication, Runyon has also been asked many times if he intends to submit this proposal to the IAU for official sanction. To this, Runyon has replied simply:

“No. Because the assumption there is that the IAU has a corner on the market on what a definition is. We in the planetary science field don’t need the IAU definition. The definition of words is based partly on how they are used. If [the geophysical definition] is the definition that people use and what teachers teach, it will become the de facto definition, regardless of how the IAU votes in Prague.”

Regardless of where people fall on the IAU’s definition of planet (or the one proposed by Runyon and his colleagues) it is clear that the debate is far from over. Prior to 2006, there was no working definition of the term planet; and new astronomical bodies are being discovered all the time that put our notions of what constitutes a planet to the test. In the end, it is the process of discovery which drives classification schemes, and not the other way around.

Further Reading: USRA

Image Source: Planetary Society

This had made me decide to create my own definition that I think will work (for me). Instead of one word for this topic, I will have two words.

A planet is, more or less, the IAU version of the definition. They are the major bodies of a solar system. This allows for simple memorization whenever we begin categorizing solar systems that aren’t just ours because, let’s be honest, 110 planets in each solar system would be impossible for our minds.

A world, as a scientific definition, is this new definition. Pluto doesn’t have to planet. It’s far enough out and is elliptic enough that I’m fine resigning it as a Kuiper Belt object like Ceres in the Asteroid Belt, however, Pluto is still a world unto its own, and a very important one at that, just like Europa, Titan, the Moon, Earth even.

The IAU gets to keep their definition, after all, planet literally means wandering star, which concerns orbits if nothing else and would create a good summary of any solar system, but anybody who is familiar with Pluto, Ceres, or various moons around the gas giants knows that those are important to us as much as the other planets. So, these are worlds, the more detailed look at a solar system and important for things pertaining to more than just orbits.

In my opinion, this creates an even better situation concerning education because rather than just learning how to distinguish the main 8 (or perhaps 9 soon), they can get to look at aspects that are as inherent to a body as water is to Earth, especially since we have at least 110 examples and soon we could be setting up shop on them.

The current definition of the planet is really troublesome.

In such case, the Earth itself is not a planet because our planet has not cleared the path (neighborhood). We are orbiting around the Sun together with Asteroid 2016 HO3 and therefore, our planet Eart is just a planetoid. Right?

Not exactly. Neither Earth nor Jupiter, or any other planet that has asteroids that lead or follow it, are “sharing” their neighborhood with other objects. They dominate these objects, which is why they lead and follow their orbits. The same cannot be said about Pluto, Eris, or any large bodies in the Main Asteroid Belt or Kuiper Belt. Here, objects follow their own orbits around the Sun.

Might have been worth looking for the current version of Emily Lakdawalla’s montage, with Pluto, Charon and Ceres up to date.

Here it is: https://planetary.s3.amazonaws.com/assets/images/comparisons/20151102_worlds-under-10k-half-phase.png

No? Oh well.

“Clearing one’s neighborhood” seems to be misunderstood by people who hate the IAU definition. It just means that the “Planet” is the dominant body in its orbit, and all the other objects remaining are just a fraction of its mass. Look at Jupiter, it has a lot of trojan asteroids, yet it has more than 99% of the mass in its “neighborhood”. Same with the Earth, or any other “Planet”. Now look at MPC-134340, it doesn’t even contain 1% of the mass of its neighborhood.

The geophysical definition could work. But like the IAU definition, it only works for certain fields and cannot be used across the board. I think we can live with several distinct but related definitions. It has worked in some extent in biology.

In the life sciences, different disciplines have different definitions of the word “species”. Population geneticists have one definition, field biologists have another. The most commonly used definition is the “biological species concept”, which defines species as genetically isolated populations of creatures that can interbreed and produce viable fertile offspring from within its group but not with other groups.

It works for most cases, but how about paleontology? You can’t infer interbreeding from fossils. So paleontologists have to rely on morphological similarities as basis for their definition of species. Of course, neontologists would point out that modern creatures with similar morphologies can be genetically isolated from each other, and that even individuals of one species can have a diversity of forms. If paleontologists did not know that caterpillars and moths are just phases in the life of a certain species, they might categorize them as distinct species, even distinct genera!

So there is no satisfactory definition for some scientific categories. Classification is just a pain, ask any systematist. I think we should allow different definition for specific subgroups in a field. Astrophysicists can use the IAU definition, while planetary physicists and geologists can use the geophysical definition. And if it proves unsatisfactory for another sub-discipline, then they can make their own definition, just as long as it is relate-able in some sense with the established definitions. The cosmos can be a messy place.

(And I still think the nostalgia factor is involved in the pro-Pluto crowd.)

Darn! You beat me to it!

Great article Matt, because talking about Pluto (and what constitutes a planet) is a popular subject with us commenters. Now where is Laurel?

p.s. Said it before, I’ll say it again: “Makemake” is one of the best names! For KBO’s my favorite would still be “Sedna” however.

Don’t worry. Laurel will chime in eventually. I saw her posting about the geophysical definition on her blogspot last week.

Sedna is indeed a great TNO. But I think it’s an SDO, not a KBO. Have you read Mike Brown’s book “How I Killed Pluto”? It’s a biographical story of how he became an astronomer and how he helped discover many of the massive TNOs so far.

Another good book (that thankfully doesn’t have a chapter on engagement rings) is Alan Boyle’s “The Case for Pluto.”

Yeah, I think you are correct Dan. It would be considered a SDO.

Hello, and thanks for thinking of me! I applaud Matt for acknowledging this issue is a matter of ongoing debate. In response to Dan, it isn’t nostalgia that motivates the “pro-Pluto crowd”; it’s preference for a geophysical planet definition.

Pvt.Pantzov says: “For KBO’s my favorite would still be “Sedna” however.”

Alas, poor Pantzov, some things are not to be!

yes, I have already received my rebuke from Dan 🙂

I disagree with the comments about Jupiter. The definition states ” (c) has cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.”

Jupiter has failed to do that as both in front of its orbit and behind it are a group of asteroids.

That definition to me means that there are no other objects in its orbit besides moons in orbit around the planet. Since these asteroids are in the way of Jupiter’s orbit, whether there is a danger or not of the two ever meeting, the orbital plane has not been cleared around its orbit, and by the same definition that dropped Pluto from being a planet, so should Jupiter!

You can’t selectively apply the rules to one’s whims.

I think I’ll post a response that was sent to us by someone from UCLA. His words addressed this confusion towards the IAUs definition quite well:

“Indeed, NEOs are constantly injected into planet-crossing orbits, and Earth constantly clears them out of the way, with time scales of ~ten million years (e.g., Gladman et al., Science, 1997). That is precisely what orbit clearing means, and what the IAU intended. No one expects Earth to clear its zone instantaneously. It is incorrect to state that Earth cannot clear its zone. It does so quite effectively.”

I partially agree with this possible new definition. But I think it can be merged with the current one by the AIU, if they take out “regardless of its orbital parameters”. I think the orbital parameters matter.

Regarding the “clearing the neighborhood”:

I’m baffled as to why the resolution isn’t more clear on this! It’s incomplete! This should have been made more aware in the document and to the public in general. It’s due to being incomplete, that people think Earth and other planets shouldn’t be planets under the new definition (“oh, the Earth has the Moon, it hasn’t cleared its neighborhood, so under the definition, it isn’t a planet”).

What the definition lacks, is that “clearing the neighborhood” means “clearing the orbital neighborhood of OBJECTS OF SIMILAR SIZE!!” Of similar size, not ALL objects:

– there’s no other body as big as the Earth, near the Earth;

– there’s no other body as big as Jupiter, near Jupiter;

– and so on.

But there are bodies as big as Pluto, near Pluto. Which is why it is a dwarf planet.

I think the definition should indeed be revised, but to include a better understanding of what “clearing the neighborhood” really means.

Actually, there aren’t any bodies as big as Pluto anywhere near Pluto. If there were, scientists on the New Horizons mission would not have had such a difficult time finding a second target for the spacecraft to visit. It took the Hubble Space Telescope to locate the nearest target, and that is a small KBO nowhere near Pluto’s size located one billion miles beyond Pluto! Eris, Haumea, and Makemake are closer to Pluto’s size, but they are not located anywhere near Pluto or near one another.

Neptune’s gravity affects Pluto’s orbit. Therefore, Pluto hasn’t cleared its orbital neighbordhood. That alone is enough to relegate it to dwarf planet: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clearing_the_neighbourhood

I am currently reading Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, which is an old book, and yet still very relevant to today. In it Pluto is, without dispute, a planet. There are countless books written before the declassification of Pluto.

Although now to re-instate Pluto as a planet would once again create text books that are incorrect.

My suggestion is to call the nine planets the original nine and give them special status because they were discovered first, the rest are all planets, just not the original ones. I also considered calling them the major planets, but this leaves a dilemma, in case we have to name planet x or planet 9, which is thought to be massive and gravitationally affecting other Kuiper belt objects.

My actual opinion is that all human classifications are arbitrary anyway, so I think it is ok to be classed in different ways by different bodies.