Despite the name, a “planetary nebula” has nothing to do with planets. They were given the confusing name 300 years ago by William Herschel because they looked like planets in their early, rudimentary telescopes. They’re really the glowing shells of gas and dust puffed out by stars nearing the end of their lives. But wait, planets might be responsible after all.

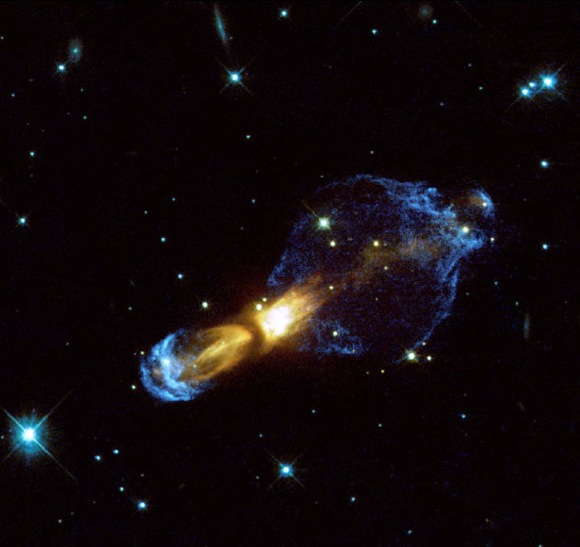

And as a special bonus for actually reading this article, I’ll treat you to a gallery of beautiful planetary nebulae.

Astronomers at the University of Rochester have announced that low-mass stars, and maybe even super-Jupiter-sized planets might actually be responsible for the beautiful puffy nebulae. Their research appears in the latest editions of the Astrophysical Journal Letters and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Most medium-sized stars, like our own Sun, will end their lives as planetary nebulae. Even though the star has lived for billions of years, this stage just lasts several tens of thousands of years. The star runs out of fuel, its core contracts, and it ejects the outermost layers of its atmosphere into space. The expanding shell can be spherical in shape, but its often twisted and elongated.

Astronomers used to think that powerful magnetic forces shape the nebula. But maybe the low-mass companion star or super-Jupiter planet might be providing the gravity that warps and distorts the shape of the nebula.

The Rochester team studied the interplay between a companion star or planet and the expanding envelope of material given off by a dying star. When the star or planet is in a very wide orbit, its gravity drags some of the envelope material around on its orbit. This creates spiral waves of nebula material that expand out from the star, bunched up by interactions with the star or planet.

There could be an entirely different effect when the companion orbits within the envelope of the dying star. It could spin up material more quickly, ejecting it into a large disk around the star. It might also work with the star’s magnetic field to force material into jets out the poles.

Of course, a companion orbiting too close to the parent star might get shredded into a debris disk orbiting the dying star. And this disk could interfere with the nice smooth expansion of stellar material.

It might be that companion stars and large planets might be responsible for the beautiful shapes we see.

Planets might be needed for planetary nebulae after all.

Original Source: University of Rochester News Release

Those are some of the most amazing photos I’ve ever seen. Were those taken with the Hubbel Telescope or where they false-colored using infrared cameras?

Words are not quite enough !! WOW !

It seems that William Herschel is even more amazing than he is generally considered, being able to “discover” planetary nebulae 30 years before he was born. Or perhaps he had a TARDIS too!

that’s so interesting. Makes perfect sense too. Fraser.

that’s supposed to say “thanks Fraser”. Love my iPhone but its hard to proofread.

words will not quite be enough //?? WOW !!

I have some serious doubts about this theory, mainly because we really still don’t know the full mechanism of their formation. Most of these examples are of bipolar planetary nebulae, which are different than ordinary planetaries.

The effects are more likely due to the close stellar companions, magnetic fields and rotation of the star itself. The loss of material from the star starts well before the planetary nebulae phase starts, when an AGB (Asymptotic Giant Branch) stars discards the outer atmosphere of the star into interstellar space via strong winds prior to the exposure of the hot white dwarf that illuminate the nebulae of the planetary itself.

Nonetheless, the existence of planets surround surrounding stars seems to predicate that they also exist around stars through the planetary nebulae phase. However, the effects of these are doubtful, as the size of a Jupiter-like object compare to the highly pregnant red-giant is literally insignificant. Furthermore, I am unaware that the ionic charged solar winds radiating at such high velocities would be changed by planets, except of course by the solar winds.

Another issue is that many examples of planetaries are in the vast majority are close binary systems – which would have much great effects on the shape of the expanding nebulosity than any planet.

Still, I would doubt we will be able to prove this directly, as detecting planets around any current planetary would be possible because of the great distance of these colourful objects. It is certainly not as easy as visible stars so far being examined by current exo-planetary observers.

Anyway, this might be eventually proven in theory to be a major factor.

One thing I do agree with – planetaries sure make spectacular astronomical vistas to look at. Just looking at these images presented here take you breath away – novice and astronomer alike.

Regards,

Andrew.

Note : I have an general article on planetary nebulae that some might like to read, which explains a little more about planetaries. See;

http://homepage.mac.com/andjames/Page091.htm

WOW!!! Creator of the Universe………..

Thank you for giving men & women the wisdom and knowledge to get information like this to us who could never enjoy it otherwise. Thank you for Universe Today and for such beauty!

Jesus is the Mind behind all the great minds.

JESUS IS LORD!!!

LL

what a beautiful set of photographs.

thanks

Absolutely stunned! Thank you, thank you, thank, you.

The reason that most of the exoplanets that have been detected are close to their stars is because those are the easiest ones to detect. Observational bias.

No doubt, there should be planets around some of the stars that are shedding matter. It isn’t unreasonable to think that they may interact with the material, and it is very feasible that strange patterns would occur as a result.

Hopefully, additional observations can give us better clues to the dynamics of these objects.

Side note: I think the term “planetary nebula” is misleading, and should be replaced with Expulsion nebula, or something similar.

subhanallah, Allahuakbar! what a beautiful images