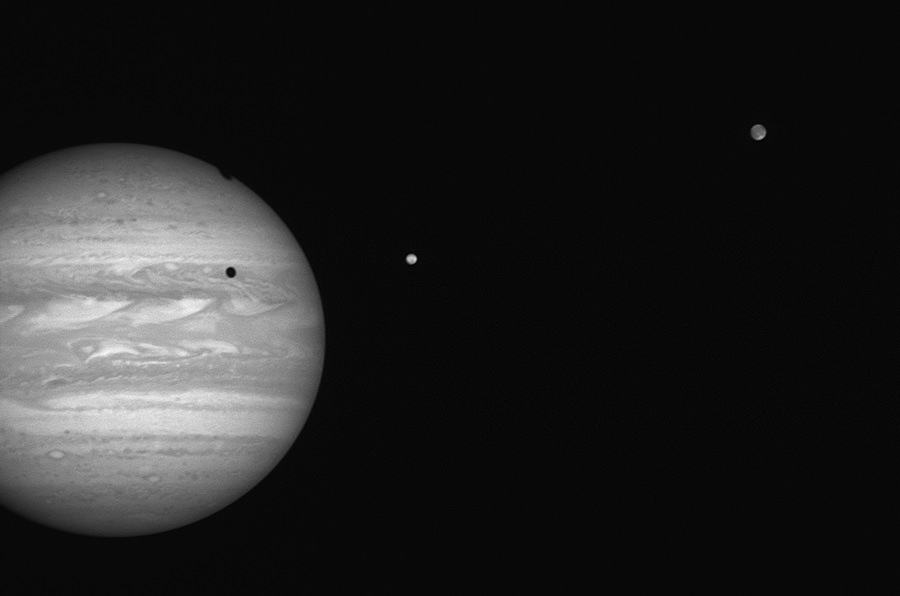

Watching the inky-black shadow of a Jovian moon slide across the cloud-tops of Jupiter is an unforgettable sight. Two is always better than one, and as the largest planet in our solar system heads towards opposition on March 8th, so begins the first of two seasons of double shadow transits for 2016.

With an orbit of 1.8 days, shadow transits of the innermost Galilean moon Io are by far the most common. The innermost three large moons of Jupiter (Io, Europa and Ganymede) are in a 1:2:4 resonance, meaning that double shadow transits involving Io and Europa and the most common. With an orbital period of 16.7 days, outermost Callisto is the only large moon of Jupiter that can occasionally ‘miss’ transiting the disk of Jove, owing to its slight 0.2 degree orbital inclination. The current ongoing season of Callisto transits wraps up this year on September 1st, and will not resume again until late 2019.

Here’s a selection of favorable double shadow transit events this coming Spring for North America:

February 26th (Io-Europa) from 9:39-10:01 UT

March 4th (Io-Europa) from 11:32-12:38 UT

March 8th (Io-Europa) 00:28-01:56 UT

March 15th (Io-Europa) 2:21-4:34 UT

March 22nd (Io-Europa) 4:23-7:10 UT

March 29th (Io-Europa) 7:00-8:24 UT

April 5th (Io-Europa) 9:36-10:17 UT

April 12th (Io-Europa) 12:11-12:14 UT

May 7th (Io-Callisto) 4:38-5:44 UT

You can see a complete list of double shadow transits worldwide for 2016 here.

The first good event of the series kicks off this week early on the morning of Friday, February 26th, and the series runs until May 7th. The second season of the year runs from August 7th to November 8th but is less than favorable, as Jupiter reaches solar conjunction on September 26th, and is hence near the Sun when the next series occurs. We combed through all mutual shadow transit events for 2016, and found 27 overall.

You can see a shadow transit of the moons of Jupiter using a telescope as small as a 60mm refractor. A 6” reflector readily reveals the shadows of the moons. Follow the four large moons, and you’ll soon be able to tell which moon is casting a shadow just by its size and appearance: innermost Io casts a small, sharp black dot, while outermost Callisto’s shadow looks grayish-ragged and diffuse.

Triple plays involving three simultaneous shadow transits are rare, but do indeed occasionally occur. Jean Meeus notes the last such a triplet occurred on January 24th 2015, and the next will occur on March 20th, 2032.

Can all four large moons ever transit? The short answer is no, or not at least as seen from the Earth in our current epoch; the orbital resonance of the inner three satellites always assures that either Europa or Callisto is the ‘odd moon out,’ leaving laggard Callisto to complete a rare cosmic triplet.

Another rarity are mutual eclipses and transits involving the moons of Jupiter themselves. The most recent series wrapped up in 2015, and won’t begin again until 2020.

Beyond celestial beauty, transits of the Galilean moons have a historical significance as well. 17th century navigators once proposed using shadow transits sighted at sea to get a fix on the time, and with it, their current longitude. The idea is sound—and was applied with some success to lunar eclipses—though following a tiny shadow of a moon from the pitching deck at sea would be difficult to near impossible, at best!

Danish astronomer Ole Rømer also noted discrepancies in the predicted times of events involving Jupiter’s moons at various points along its orbit, and correctly deduced that the speed of light was to blame. He used this insight to make a pretty good stab at the now famous value of c…. not bad for 1676.

And speaking of mutual events of the moons of Jupiter, such phenomena are very similar to total solar eclipses on the Earth, though they’re much faster…

Perhaps one day, our eclipse viewing hotel on Callisto will be open for business. In the meantime, don’t miss a chance to witness a double shadow transit this opposition season, gracing the good old skies of the Earth.

Send those double shadow transit pics in to Universe Today’s Flickr page.

Next up: our complete guide to the 2016 opposition season for Jupiter next week.