The strangest feature on Iapetus is the equatorial ridge. What could possibly create a feature like this?

To paraphrase the British geneticist J.B.S Haldane, “in my suspicion, the Universe is not only stranger than we suppose, it’s stranger than we can suppose.” The context was life and evolution, but he might as well been talking about Saturn’s moons. Those teeny worlds are some of the strangest places we’ve ever seen.

Titan is a massive moon with an atmosphere thicker than Earth’s. If it wasn’t for the bone crippling cold and unbreathable atmosphere, you could wear a pair of wings and fly around in the Titanic skies.

There’s Enceladus, an icy moon that blasts water out into space through geysers at its southern pole. But the Saturnian moon that fascinates me the most has got to be Iapetus, also known as Saturn’s yin-yang moon.

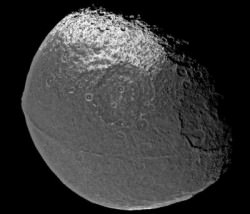

Here’s a photo captured by Cassini. Check out the bizarre surface features, where half of the moon is icy white and the other is brownish red. Astronomers believe this strange coloration comes from the ice on the warmer side sublimating away, leaving this darker material beneath.

Sure that’s a bit odd, but the strangest feature on Iapetus is the equatorial ridge. This feature measures 1,300 km long and it makes the moon look like a space walnut. Because of the heavy cratering on the ridge, astronomers know that it’s ancient, nearly as old as the moon itself. At 13 kms high, it’s tall enough to keep out the most persnickety white walker or wildling mammoth & giant battalion.

What could possibly create a feature like this?

Astronomers are of a few camps. The first think it formed through convective activity early on in the moon’s history. Saturn pulls Iapetus with its tremendous gravity, and the moon undergoes massive tidal forces. This generates heat in the moon’s interior, and it might have caused it to blob out at the equator.

A second idea is that Iapetus consumed one of Saturn’s rings, billions of years ago. The moon might have slowly wandered through the ring plane, and accreted all the ring material, like snow piling up in front of a plow.

A third is that Iapetus was smashed into by a massive asteroid billions of years ago. This impact caused the moon to fly apart, but then mutual gravity pulled it back together. The force of this recombination squeezed out material at the equator, which then solidified in place.

Alternately, it might be a walnut from a Galactus family Christmas stocking. So which is it?

It turns out that Saturn has two more moons in its system with similar equatorial ridges. Its moon Atlas is just 15 km across, but it’s dominated by an equatorial ridge. It looks like a UFO, and Pan has a similar feature.

Astronomers know that both of these created their ridges by pulling material out of the rings and piling it up on their surface. This is the mechanism that seems to match what’s going on with Iapetus.

One mystery, is how distantly Iapetus orbits Saturn. There’s no ring that far out, so where did it get the material to consume? Is it possible that Iapetus drifted outward, or had a ring system of its own?

You want puzzles? Iapetus is one of the strangest places in the Solar System, and it would be my candidate for a future orbiter or lander. Let’s explore it closer.

What’s your favorite bizarre object in the Solar System? Tell us in the comments below.

Ooooo. Like the gas giant planet migrations and even Neptune and Uranus switching places….. Yes…. The Jupiter and Saturn systems at least are big complex places. What an interesting idea….

Obviously it’s just the casting seam from the mold they used to make it. 😉

Wrong, Qev. See my other post.

Wrong, Qev. Sloppy aliens assembled the Revell kit and then got distracted by reports of an intergalactic war in the Fornax cluster and forgot to sand down the flash.

Interestingly, in Arthur C. Clarke’s novel ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (1968, developed from his 1948 story ‘The Sentinel’), the second monolith to be discovered by humankind was situated slap bang in the middle of the circular dark patch on Iapetus. The black and white ‘winking’ of Iapetus was the superior aliens’ ‘come hither’ signal to earthlings. What a disappointing cop-out by Kubrick that the film-version monolith was just floating in orbit around Saturn. How on earth (sorry, wrong planet) would it have been detected? Then, an actual monolith was discovered on Iapetus: http://www.theoutpostforum.com/tof/showthread.php?650-Monolith-on-Mars

It would have been hard to build a movie set that looks like a convincing Iapetusian landscape. Spraypainted styrofoam and balsa wood can only do so much.

– Moon, bright Moon up there so high, who is the weirdest in the sky?

– Fraser, Hyperion is weirdest in the sky.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/94/Hyperion_true.jpg

Hyperion is most definitely very weird and mystifying. Every time I see that picture I’m amazed all over again. But perhaps Honorable Mention should go to Comet 67P/C-G, at least from an on-the-surface viewpoint. With it’s gravitational vectors changing from point to point, a person on the surface would experience some truly mind-boggling perspectives from different parts of the comet’s surface. At places, mountains would seem to rise horizontally from the surface or one of the massive lobes would appear to be overhead.

My favourite stat about Iapetus is that its brightness in our skies varies far more over its 79 day orbit of Saturn (due to the bright face/dark face) than over Saturn’s roughly yearly opposition/ conjunction cycle.

Here I have a plea for assistance – can anyone (PLEASE!) refer me to a resource which provides accurate brightness figures for Iapetus on a daily basis?

I can only find sources which take the yearly variation into account, none which account for the more critical 79 day cycle – my usually reliable Starry Night software included.