[/caption]

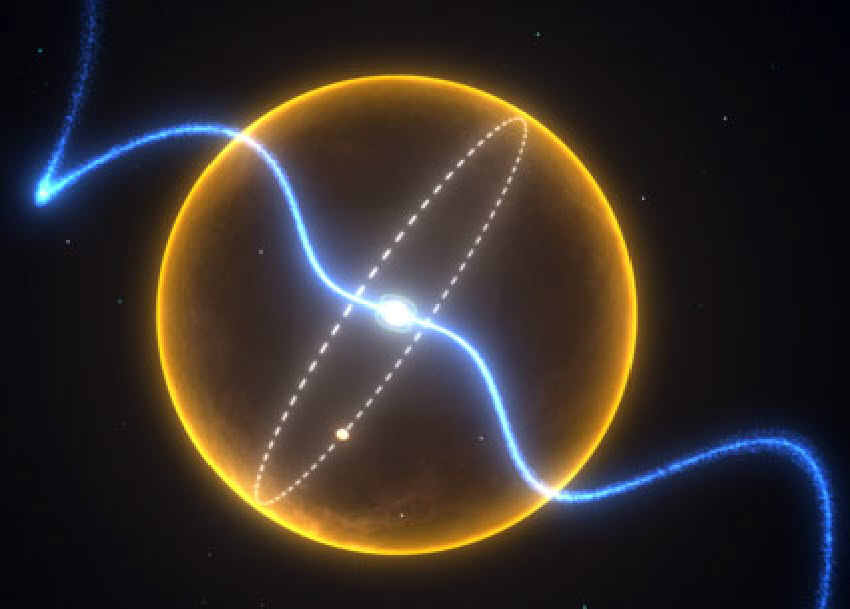

In 1996, a Japanese amateur astronomer discovered a new star in the constellation Sagittarius. Dubbed V4334 Sgr, astronomers initially expected it to be a typical novae, but closer examination revealed it to be a previously predicted but unseen event known as a “Very Late Thermal Pulse” (VLTP), the last hurrah of a white dwarf as hydrogen from the exterior of the star is carried to lower depths where one last gasp of fusion occurs. Astronomers then identified a second star, V605 Aql, that had been caught undergoing a VLTP in 1919. Recently, astronomers from the National University of La Plata, in Argentina, have claimed to have uncovered a third star undergoing this rare event.

It has been estimated that roughly one star every year ends its main sequence life and heads down the path of making a planetary nebula. Many of them won’t become convective white dwarfs that could turn into stars that should undergo a VLTP, but conservative estimates suggest that roughly 10% should. At such a rate, there should be roughly one star every decade that undergoes this phase. Since the stars have already shed their outer layers, the rejuvenated fusion is not diminished by them, and these stars shine exceptionally brightly making them detectable through most of the galaxy. Yet prior to this new identification, only two have been discovered which suggests that many objects historically identified as novae may truly have been stars similar to V4334 Sgr and V605 Aql.

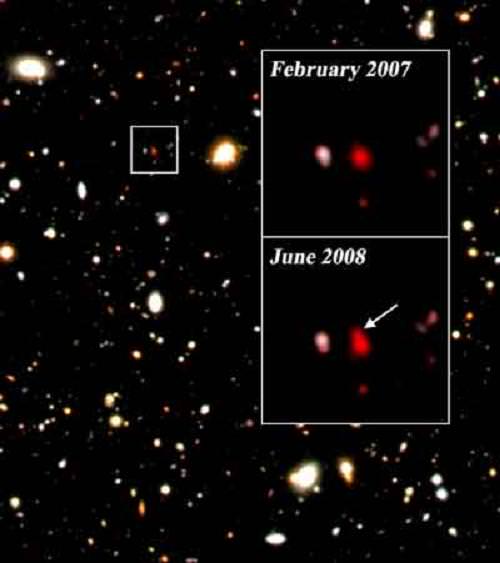

In 2005, David Williams, a member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers, gathered images from the Harvard College Astronomical Plate collection. This massive collection of over 500,000 photographic plates, was the result of an early and long running survey that photographed great portions of the sky repeatedly from 1885 until 1993. This collection allowed him to reconstruct the changes in brightness the star NSV 11749 underwent during its outburst.

The star first became visible on the photographic plates in 1899. It peaked in brightness in 1903 and remained at that brightness for several years, until 1907 when it began to fade away again. The amount of time it took to brighten as well as the total change in brightness were similar to the previously identified VLTP stars. Over the 15 years since it first became detectable, it disappeared from images several times, another feature seen in V4334 Sgr and V605 Aql. The sudden disappearance has been explained by ejections of carbon from the star which cools and forms small dust grains which are effective at blocking light in the visible portion of the spectrum until they disperse.

However, two key differences stands out: The overall time before the NSV 11749 faded was roughly twice as long as for V605 Aql and V4335 Aql. The authors suggest that this may be due to a different mass of the white dwarf behind the outbursts. If the two previously identified VLTP stars were close in mass, they would likely have similar properties, while NSV 11749 could potentially have a different mass. The second discrepancy was the presence of a young planetary nebula. In both of the previously identified cases, the stars were the center of nebulae, but infrared images of the star did not reveal any nebula or remaining dust from the previous outburst. Authors again attribute this to a different evolutionary timescale due to the star’s potentially different mass.

While this tentative new classification is hardly conclusive, it is a reminder that astronomers have only just begun to understand this phase of stellar evolution and there is a great need for further examples to help refine models. The evolution of V4334 Sgr moved roughly 100 times faster than simulations had predicted, prompting revisions to the models. Certainly, similar changes will be necessary as more VLTP stars are discovered. This era of a star’s life is important to astronomers because the light obscuring carbon ejection is expected to be a major source of this important element.