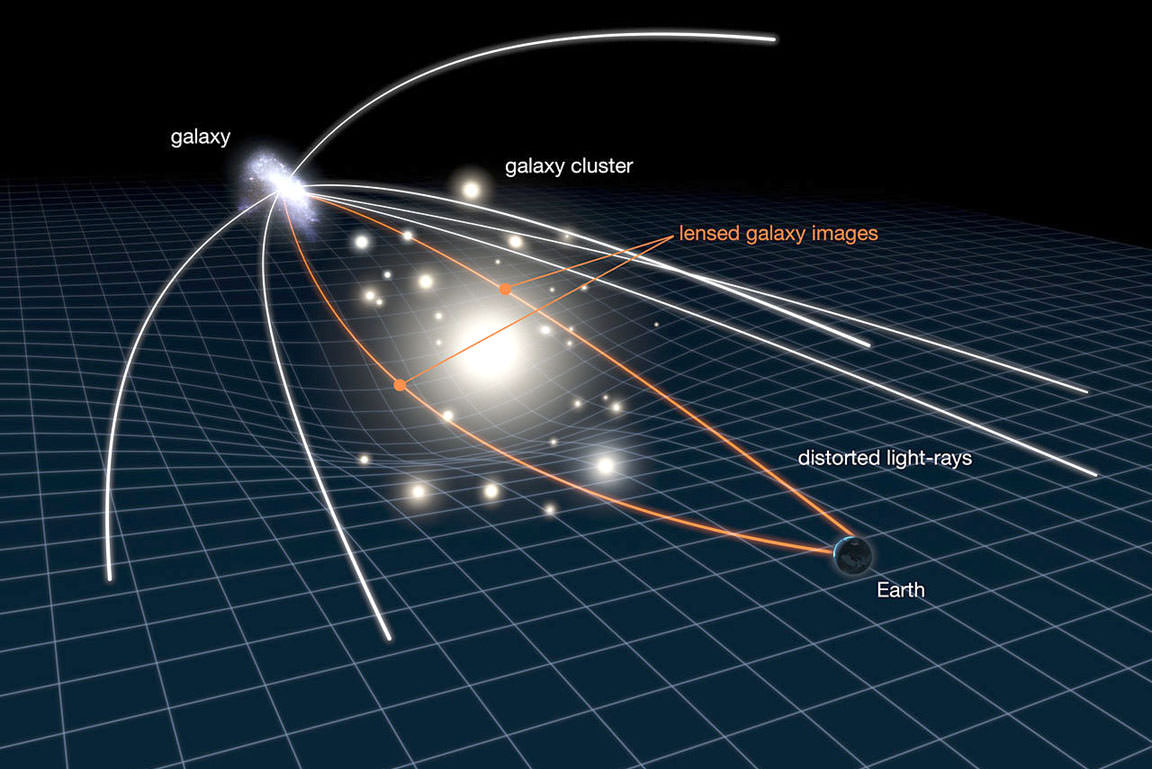

Gravitational lenses are an important tool for astronomers seeking to study the most distant objects in the Universe. This technique involves using a massive cluster of matter (usually a galaxy or cluster) between a distant light source and an observer to better see light coming from that source. In an effect that was predicted by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this allows astronomers to see objects that might otherwise be obscured.

Recently, a group of European astronomers developed a method for finding gravitational lenses in enormous piles of data. Using the same artificial intelligence algorithms that Google, Facebook and Tesla have used for their purposes, they were able to find 56 new gravitational lensing candidates from a massive astronomical survey. This method could eliminate the need for astronomers to conduct visual inspections of astronomical images.

The study which describes their research, titled “Finding strong gravitational lenses in the Kilo Degree Survey with Convolutional Neural Networks“, recently appeared in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. Led by Carlo Enrico Petrillo of the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, the team also included members of the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF), the Argelander-Institute for Astronomy (AIfA) and the University of Naples.

While useful to astronomers, gravitational lenses are a pain to find. Ordinarily, this would consist of astronomers sorting through thousands of images snapped by telescopes and observatories. While academic institutions are able to rely on amateur astronomers and citizen astronomers like never before, there is imply no way to keep up with millions of images that are being regularly captured by instruments around the world.

To address this, Dr. Petrillo and his colleagues turned to what are known as “Convulutional Neural Networks” (CNN), a type of machine-learning algorithm that mines data for specific patterns. While Google used these same neural networks to win a match of Go against the world champion, Facebook uses them to recognize things in images posted on its site, and Tesla has been using them to develop self-driving cars.

As Petrillo explained in a recent press article from the Netherlands Research School for Astronomy:

“This is the first time a convolutional neural network has been used to find peculiar objects in an astronomical survey. I think it will become the norm since future astronomical surveys will produce an enormous quantity of data which will be necessary to inspect. We don’t have enough astronomers to cope with this.”

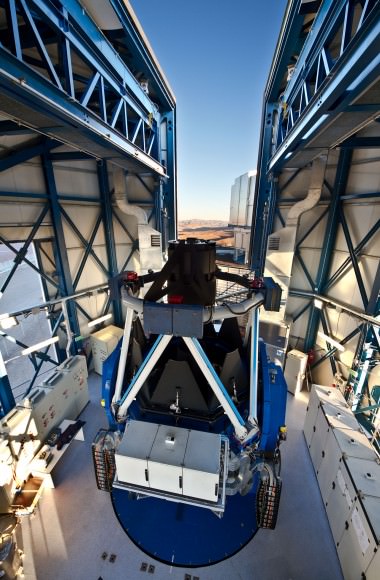

The team then applied these neural networks to data derived from the Kilo-Degree Survey (KiDS). This project relies on the VLT Survey Telescope (VST) at the ESO’s Paranal Observatory in Chile to map 1500 square degrees of the southern night sky. This data set consisted of 21,789 color images collected by the VST’s OmegaCAM, a multiband instrument developed by a consortium of European scientist in conjunction with the ESO.

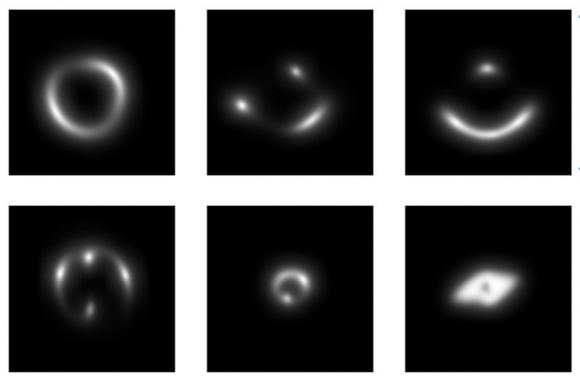

These images all contained examples of Luminous Red Galaxies (LRGs), three of which wee known to be gravitational lenses. Initially, the neural network found 761 gravitational lens candidates within this sample. After inspecting these candidates visually, the team was able to narrow the list down to 56 lenses. These still need to be confirmed by space telescopes in the future, but the results were quite positive.

As they indicate in their study, such a neural network, when applied to larger data sets, could reveal hundreds or even thousands of new lenses:

“A conservative estimate based on our results shows that with our proposed method it should be possible to find ?100 massive LRG-galaxy lenses at z ~> 0.4 in KiDS when completed. In the most optimistic scenario this number can grow considerably (to maximally ? 2400 lenses), when widening the colour-magnitude selection and training the CNN to recognize smaller image-separation lens systems.”

In addition, the neural network rediscovered two of the known lenses in the data set, but missed the third one. However, this was due to the fact that this lens was particularly small and the neural network was not trained to detect lenses of this size. In the future, the researchers hope to correct for this by training their neural network to notice smaller lenses and rejects false positives.

But of course, the ultimate goal here is to remove the need for visual inspection entirely. In so doing, astronomers would be freed up from having to do grunt work, and could dedicate more time towards the process of discovery. In much the same way, machine learning algorithms could be used to search through astronomical data for signals of gravitational waves and exoplanets.

Much like how other industries are seeking to make sense out of terabytes of consumer or other types of “big data”, the field astrophysics and cosmology could come to rely on artificial intelligence to find the patterns in a Universe of raw data. And the payoff is likely to be nothing less than an accelerated process of discovery.

Further Reading: Netherlands Research School for Astronomy , MNRAS