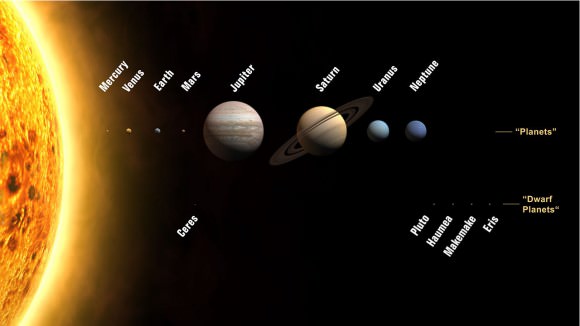

It’s is no secret that Earth is the only inhabited planet in our Solar System. All the planets besides Earth lack a breathable atmosphere for terrestrial beings, but also, many of them are too hot or too cold to sustain life. A “habitable zone” which exists within every system of planets orbiting a star. Those planets that are too close to their sun are molten and toxic, while those that are too far outside it are icy and frozen.

But at the same time, forces other than position relative to our Sun can affect surface temperatures. For example, some planets are tidally locked, which means that they have one of their sides constantly facing towards the Sun. Others are warmed by internal geological forces and achieve some warmth that does not depend on exposure to the Sun’s rays. So just how hot and cold are the worlds in our Solar System? What exactly are the surface temperatures on these rocky worlds and gas giants that make them inhospitable to life as we know it?

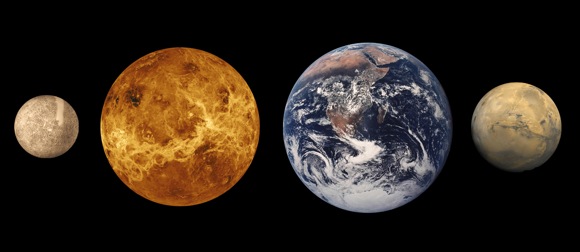

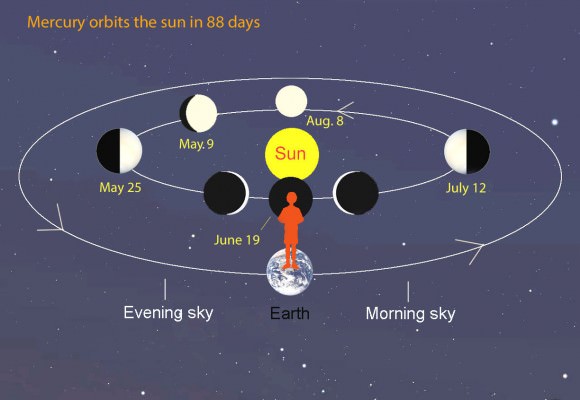

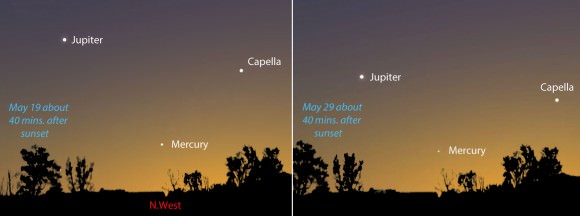

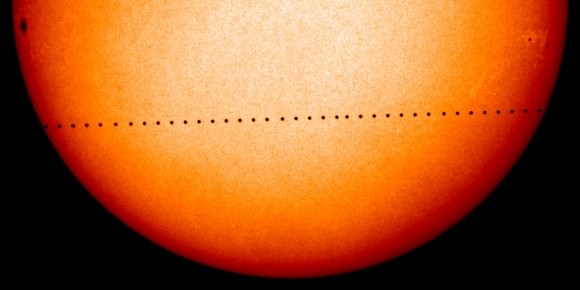

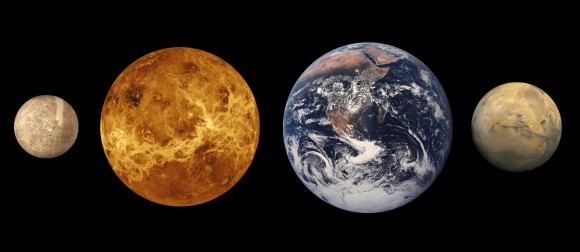

Mercury:

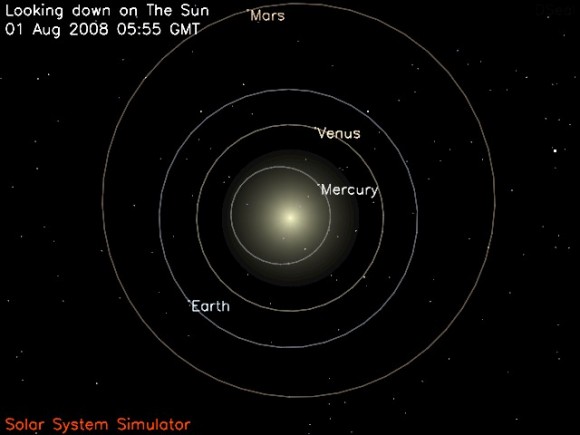

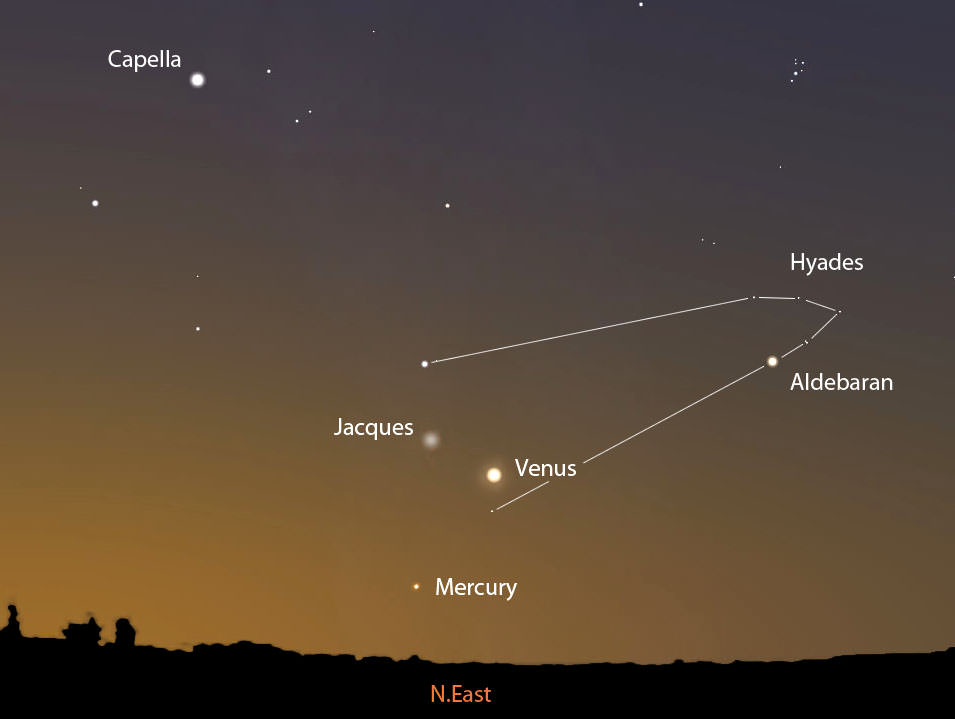

Of our eight planets, Mercury is closest to the Sun. As such, one would expect it to experience the hottest temperatures in our Solar System. However, since Mercury also has no atmosphere and it also spins very slowly compared to the other planets, the surface temperature varies quite widely.

What this means is that the side exposed to the Sun remains exposed for some time, allowing surface temperatures to reach up to a molten 465 °C. Meanwhile, on the dark side, temperatures can drop off to a frigid -184°C. Hence, Mercury varies between extreme heat and extreme cold and is not the hottest planet in our Solar System.

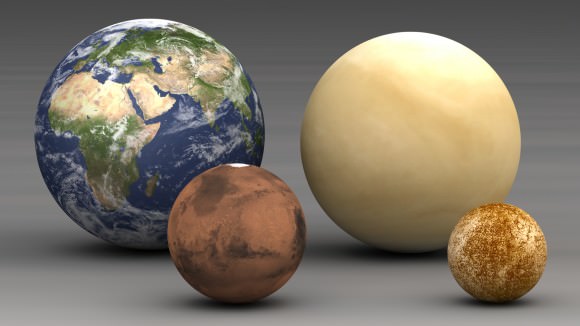

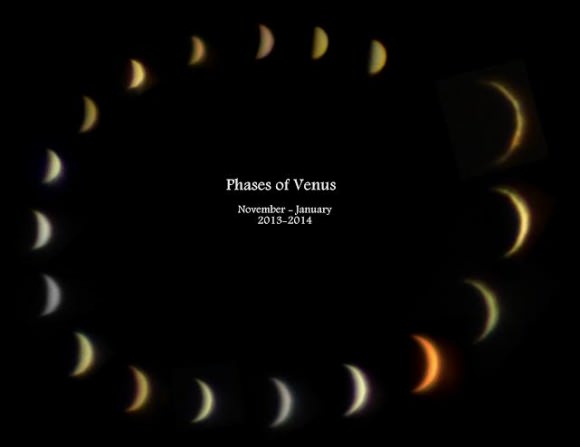

Venus:

That honor goes to Venus, the second closest planet to the Sun which also has the highest average surface temperatures – reaching up to 460 °C on a regular basis. This is due in part to Venus’ proximity to the Sun, being just on the inner edge of the habitability zone, but also to Venus’ thick atmosphere, which is composed of heavy clouds of carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.

These gases create a strong greenhouse effect which traps a significant portion of the Sun’s heat in the atmosphere and turns the planet surface into a barren, molten landscape. The surface is also marked by extensive volcanoes and lava flows, and rained on by clouds of sulfuric acid. Not a hospitable place by any measure!

Earth:

Earth is the third planet from the Sun, and so far is the only planet that we know of that is capable of supporting life. The average surface temperature here is about 14 °C, but it varies due to a number of factors. For one, our world’s axis is tilted, which means that one hemisphere is slanted towards the Sun during certain times of the year while the other is slanted away.

This not only causes seasonal changes, but ensures that places located closer to the equator are hotter, while those located at the poles are colder. It’s little wonder then why the hottest temperature ever recorded on Earth was in the deserts of Iran (70.7 °C) while the lowest was recorded in Antarctica (-89.2 °C).

Mars:

Mars’ average surface temperature is -55 °C, but the Red Planet also experiences some variability, with temperatures ranging as high as 20 °C at the equator during midday, to as low as -153 °C at the poles. On average though, it is much colder than Earth, being just on the outer edge of the habitable zone, and because of its thin atmosphere – which is not sufficient to retain heat.

In addition, its surface temperature can vary by as much as 20 °C due to Mars’ eccentric orbit around the Sun (meaning that it is closer to the Sun at certain points in its orbit than at others).

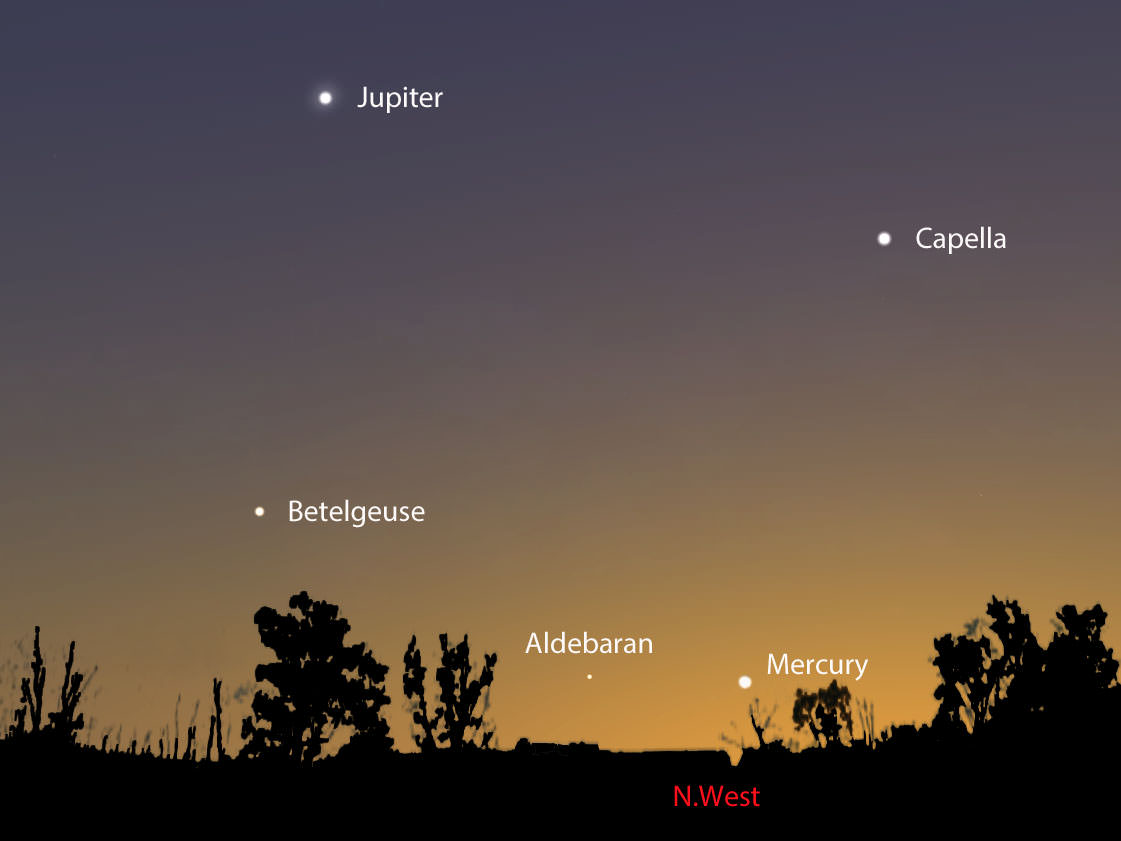

Jupiter:

Since Jupiter is a gas giant, it has no solid surface, so it has no surface temperature. But measurements taken from the top of Jupiter’s clouds indicate a temperature of approximately -145°C. Closer to the center, the planet’s temperature increases due to atmospheric pressure.

At the point where atmospheric pressure is ten times what it is on Earth, the temperature reaches 21°C, what we Earthlings consider a comfortable “room temperature”. At the core of the planet, the temperature is much higher, reaching as much as 35,700°C – hotter than even the surface of the Sun.

Saturn:

Due to its distance from the Sun, Saturn is a rather cold gas giant planet, with an average temperature of -178 °Celsius. But because of Saturn’s tilt, the southern and northern hemispheres are heated differently, causing seasonal temperature variation.

And much like Jupiter, the temperature in the upper atmosphere of Saturn is cold, but increases closer to the center of the planet. At the core of the planet, temperatures are believed to reach as high as 11,700 °C.

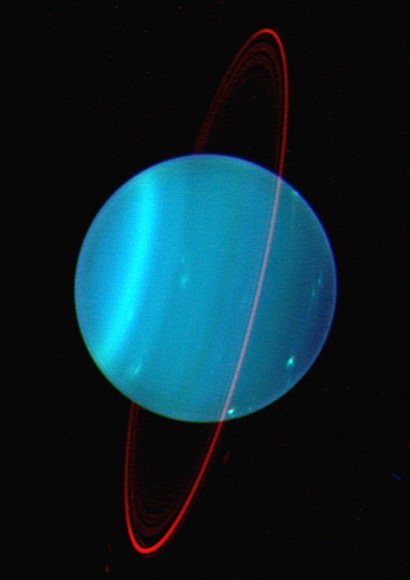

Uranus:

Uranus is the coldest planet in our Solar System, with a lowest recorded temperature of -224°C. Despite its distance from the Sun, the largest contributing factor to its frigid nature has to do with its core.

Much like the other gas giants in our Solar System, the core of Uranus gives off far more heat than is absorbed from the Sun. However, with a core temperature of approximately 4,737 °C, Uranus’ interior gives of only one-fifth the heat that Jupiter’s does and less than half that of Saturn.

Neptune:

With temperatures dropping to -218°C in Neptune’s upper atmosphere, the planet is one of the coldest in our Solar System. And like all of the gas giants, Neptune has a much hotter core, which is around 7,000°C.

In short, the Solar System runs the gambit from extreme cold to extreme hot, with plenty of variance and only a few places that are temperate enough to sustain life. And of all of those, it is only planet Earth that seems to strike the careful balance required to sustain it perpetually.

Universe Today has many articles on the temperature of each planet, including the temperature of Mars and the temperature of Earth.

You may also want to check out these articles on facts about the planets and an overview of the planets.

NASA has a great graphic here that compares the temperatures of all the planets in our Solar System.

Astronomy Cast has episodes on all planets including Mercury.